VICHY’S PÉTAIN FACES TREASON CHARGES

Paris, France · July 23, 1945

Following the military defeat of France by Nazi Germany in June 1940, World War I hero Marshal Philippe Pétain proclaimed a new French government on July 10, 1940. Pétain held the title of “President of the Council” instead of President of France. His government, which accorded him extraordinary powers, was officially called the French State, L’État Français. Unofficially, it was called Vichy France after the resort where Pétain and the National Assembly met. The French capital remained in German-occupied northern France. Vichy administered the so-called Free Zone in the south but had legal authority in both zones. When the Allies landed in Vichy North Africa in November 1942 (Operation Torch), German and Italian troops moved in to occupy the rump French state. On August 24, 1944, after four years of Vichy collaboration and German occupation, a Free French armored division under the command of Gen. Jacques Philippe Leclerc liberated the French capital. The next day Free French head Gen. Charles de Gaulle, who had set up a provisional government (gouvernement provisoire de la Republique francaise) on French soil during the Normandy campaign, entered Paris and within a week had installed his government in the liberated capital. Pushing his myth of France as a nation of united resisters betrayed by a handful of traitors (the truth was, most French, especially those in military and government service, supported the Pétain regime), de Gaulle pressed a program of national reconciliation on his countrymen. That said, over 300,000 suspected French collaborators—including some of the more than 40,000 men who joined the French paramilitary Milice, scourge of the Resistance—were turned over to various courts of justice. Of those, 764 were executed. On this date in 1945 Vichy head Pétain was placed on trial and three weeks later was sentenced to death. De Gaulle commuted the 89‑year‑old’s sentence to life imprisonment. Pierre Laval, Prime Minister of Vichy France, and Milice chief Joseph Darnand were executed. Many collaborators—for instance police who had organized raids to capture Jews and others considered “undesirables” by the Germans in both French zones—soon resumed official duties. In 1955 amnesty fever broke out and ten years later all jailed French collaborators were free persons.

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”ASINList” width=”600″ height=”200″ title=”Recommended Reading” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”False” show_border=”False” asin=”0631139273,1846030765,0199254575,0199539324,1403970114,0815410433,1847373925,1565843231,0312423594,0810941236″ /]

Occupied France and Prominent Vichy French Collaborators

|

Above: Pre-liberation occupation zones of France, 1940–1944.

|  |

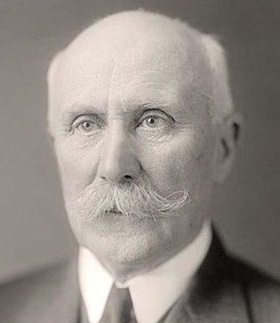

Left: Philippe Pétain (1856–1951) was a French general who reached the distinction of Marshal of France, later authoritarian Chief of State of Vichy France from 1940 to 1944. Over the years Pétain and his Vichy regime collaborated ever more closely with their German occupiers. His wartime actions resulted in his postwar conviction for treason (by a one-vote majority) and death sentence. Gen. Charles de Gaulle, who was President of the Provisional Government of the French Republic, commuted the sentence to life imprisonment due to Pétain’s advance age and his military contributions in World War I. Pétain was exiled to an island prison off the French Atlantic coast, where he died at the age of 95.

![]()

Right: Pierre Laval (1883–1945) was four-time Prime Minister of France, twice serving the Vichy regime as head of government. An admirer of totalitarian government, Laval embraced the cause of fascism, the destruction of democracy, and the dismantling of the democratic Third Republic. He signed orders sanctioning the deportation of foreign Jews from French soil to the Nazi death camps. On September 7, 1944, what was left of the Vichy government moved to Sigmaringen in southwestern Germany. After falling into U.S. hands, Laval was turned over to the French government in late July 1945. Tried for treason and violating state security, he was convicted and sentenced to death. After a failed attempt at suicide (the cyanide had lost its full potency), Laval was executed, half-unconscious and vomiting, by firing squad on October 15, 1945.

|  |

Left: A far-right veteran from the First World War, Joseph Darnand (1897–1945) founded a militia in 1941 that supported Philippe Pétain and Vichy France. In January 1943 he transformed the organization into the notorious Milice Française (Milice). In October 1943 Darnand took an oath of loyalty to Adolf Hitler and received a rank of Sturmbannführer in the Waffen-SS. In December 1943 he became head of police and later secretary of the interior. Darnand expanded the Milice and by 1944 it had over 35,000 members. After the Normandy invasion and Allied advance, Darnand joined Pétain’s government in southwestern Germany in September 1944. The next April he fled to Northern Italy, where he arrested and hauled back to France. Tried and sentenced to death, he was executed by firing squad on October 10, 1945.

![]()

Right: Jacques Doriot (1898–1945) founded the ultra-nationalist, pro-fascist Parti Populaire Français (PPF) in 1936. Doriot became a staunch supporter of the Nazi occupation of northern France in 1940. He moved to Paris, where he espoused pro-German and anti-Communist propaganda on Radio Paris. In 1941 he co-founded the Légion des Volontaires Français (LVF), a French unit of the German Wehrmacht. The LVF saw active duty on the Eastern Front. When the unit was all but destroyed, Doriot fought in the Wehrmacht and was awarded the Iron Cross in 1943. After France’s liberation the PPF was involved in conducting intelligence and sabotage activities by supplying men whom the Germans dropped by parachute into liberated France. Doriot was killed in late February 1945 when his car was strafed by Allied fighters.

Marshal Philippe Pétain’s Treason Trial

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click