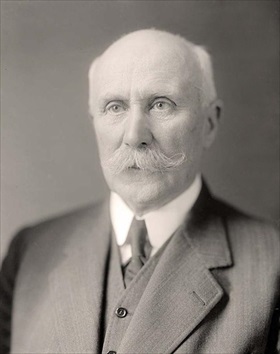

PÉTAIN, MARSHAL PHILIPPE (1856–1951)

Pétain’s defense at the ten-month-long Battle of Verdun during World War I made the then general a national hero. During the crisis of May 1940, when Hitler launched his blitzkrieg offensive in the West, it became clear that French forces were overwhelmed and that military collapse was imminent. Maréchal (Marshal) Pétain, who had been called out of retirement to serve as French vice-premier, took the position that it was best if the French government remained in France rather than move into exile following the Norwegian and Dutch model. When Prime Minister Paul Reynaud resigned over his insistence that France continue to fight Germany from abroad, President Albert Lebrun appointed Pétain to the top post. Pétain sought an armistice with Germany, and an agreement was reached on June 22, 1940.

In the peace that followed, the French Parliament, composed of the Senate and the National Assembly, granted Pétain full and extraordinary powers. Two days later, on July 12, 1940, under the authority of a new constitution, “President of the Council” Pétain began turning his regime into a non-democratic government collaborating with Germany. Among the new measures were the dismissal of civil servants, the installation of exceptional jurisdictions, the proclamation of anti-Semitic laws, and the imprisonment of opponents and foreign refugees. Censorship was imposed, and freedom of expression and thought were criminalized as “felonies of opinion.” Pétain’s government countenanced the creation of a collaborationist armed militia, the Gestapo-like Milice, which along with German forces rounded up Jews, communists, and dissidents while leading a campaign of repression against the French resistance, Maquis. France was reduced by drastic rationing to a nation in perpetual need.

The 1940 armistice divided France into occupied and unoccupied zones: Northern and Western France, including the entire Atlantic coast, which all together comprised most of the nation’s industrial capacity, was occupied by Germany, and the remaining two-fifths of the country was governed by the French government with the administrative capital at Vichy under the figurehead Pétain. Paris remained the de jure capital. Ostensibly Vichy administered the entire nation.

Pétain’s southern zone remained under his control until the Allies invaded French North Africa in November 1942, at which time the Wehrmacht (German armed forces) moved into the southern zone from the northern and western parts of France. Following the June 1944 Allied invasion of France in Operation Overlord, Pétain’s leadership was challenged by Free French leader Gen. Charles de Gaulle, who proclaimed the Provisional Government of the French Republic. With the liberation of France in August and September 1944, Pétain and his Vichy government fled to Sigmaringen across the German border and established, of all things, a French government-in-exile recognized by Vichy allies Germany, Italy, and Japan. The city was captured by the French army on April 22, 1945, and days later Pétain returned voluntarily to France.

De Gaulle’s provisional government charged the 89-year-old Pétain with treason and placed him on trial (July 23 to August 15, 1945). He was convicted and sentenced to death. De Gaulle commuted the sentence to life imprisonment on grounds of Pétain’s advanced age and recognition of his World War I contributions. He died at Ile d’Yeu, an island off the French Atlantic coast, on July 23, 1951, at the age of 95 and is buried in a nearby marine cemetery. From time to time calls are made to re-inter his remains in the grave prepared for him at Verdun.

Pétain’s legacy is ambiguous. Stripped of all his honors but one, Marshal of France, his surname is forever sullied: pétainisme is a derogatory term for reactionary politics associated with his discredited regime.

![]()

Enthusiastic French Crowds Greet Marshal Philippe Pétain on His Historic Visit to German-Occupied Paris, April 28, 1944 (French-Language Newsreel)

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click