JAPANESE SUB SHELLS U.S. WEST COAST

Santa Barbara, California • February 23, 1942

Japanese submarines initiated the first shore bombardments of the war with an attack on the U.S. Navy base at Johnston Island in the Pacific in mid-December 1941, just days after Japanese carrier-based planes had destroyed, in their surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, one‑half of the United States’ naval power. Japanese submarines briefly shelled the American Pacific outpost on Midway Island in January 1942. The following month, on this date, February 23, 1942, Japanese skipper Kozo Nishino ordered his submarine, the 2,500‑ton I‑17, to launch the first enemy attack on the U.S. mainland since the War of 1812. Shortly after 7 p.m., I‑17 surfaced about 12 miles/19 km west of the city of Santa Barbara, California, and for the next 20 minutes fired 17 or 25 rounds (sources vary) from her 140 mm/5.5 in. deck gun at the Richfield (later ARCO) aviation fuel storage tanks on a bluff behind the beach. The shots badly missed the tanks but destroyed an oil derrick and damaged a pier and a pump house to the tune of $500. (The site is now a golf course.) Kozo radioed Tokyo that he “left Santa Barbara in flames.” News of the Ellwood oil field shelling triggered an invasion scare up and down the West Coast, as the Japanese had hoped. (The I‑17 met her demise on August 19, 1943, off Noumea, New Caledonia, about 900 miles/1,500 km east of Australia, sunk by a New Zealand trawler and 2 U.S. Navy PBY Catalina flying boats.)

Two nights later trigger-happy U.S. Army anti-aircraft batteries exploded into action over the blacked-out city of Los Angeles. During a 30‑minute fusillade, guns hurled 1,440 rounds of 3‑inch and 37‑mm ammunition into the searchlight-swept night sky. About 10 tons of shrapnel and dud shells fell back on the city of 1.5 million people, damaging residences, shipyards, and aircraft plants where late-night shifts were at work. Eight people died that night, 3 of heart attacks, the others in accidents related to the blackout. At a press conference shortly afterward, Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox called the incident, known in contemporary media as “The Battle of Los Angeles” or “The Great Los Angeles Air Raid,” a “false alarm” stemming from “war nerves.” Actually, the false alarm was touched off by a weather balloon.

Not everyone bought the government’s assurances. The California Long Beach Independent editorialized: “There is a mysterious reticence about the whole affair and it appears that some form of censorship is trying to halt discussion on the matter.” Others speculated that the incident was either staged or exaggerated to give defense industries like Douglas (now Boeing) Aircraft then in Long Beach and in Santa Monica an excuse to move further inland. (Secretary Knox encouraged their moving.)

The Great Los Angeles Air Raid was front-page news and fodder for newspaper editors around the nation. Americans were living through scary times, so people believed. Many West Coast residents imagined the worst—that after the surprise Japanese air and naval attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, 2½ months before, enemy planes might suddenly show up in the middle of the night and unload their bombs on their own communities, or that a Japanese invasion force might appear off their undefended beaches, hook up with tens of thousands of American-born Japanese (Nisei) and Japanese nationals living among them (50,000 in Los Angeles alone), and jointly unleash mayhem and destruction. Truth was, as it turned out, during 1941 and 1942 I‑17 was one of 10 Japanese “cruiser” (I‑class) submarines that routinely patrolled off the Pacific West Coast, Alaska, and Baja California, never to bag a high-value target like a battleship or an aircraft carrier. And, with the exception of sinking a handful of oil tankers, a single cargo steamer, and 1 Soviet mine-laying submarine, followed in 1944 and 1945 by hundreds of explosive-laden hydrogen-filled balloons (fūsen bakudan) Japan sent aloft on the jet stream to drop, hit or (mostly) miss, on the North American continent, . . . well, that was about as scary as it really ever got for West Coast residents.

The Japanese Sub I-17 Brought War and Pandemonium to the U.S. Mainland. More Japanese Subs Were on Their Way to the West Coast

|

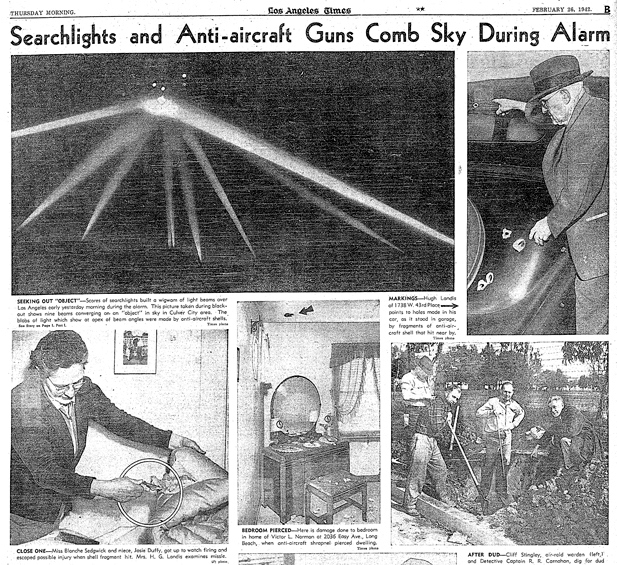

Above: The February 26, 1942, Los Angeles Times edition covered the “Battle of Los Angeles” and its aftermath. Times headlines screamed: “ARMY SAYS ALARM REAL.” In a front-page editorial the newspaper stated that “considerable public confusion and excitement” had been caused by the air raid alert. In some of the most imaginative reporting of the war, articles described shrapnel-strewn areas of the city, property damage, and people finding unexploded ordinance. The rival Los Angeles Examiner described “shrapnel-strewn” neighborhoods that “took on the appearance of a huge Easter-egg hunt [as] youngsters and grownups alike scrambled through streets and vacant lots, picking up and proudly comparing chunks of shrapnel fragments.” The Army roped off entire streets, placing large signs at both ends warning “DANGER UNEXPLODED BOMB.” There were no unexploded bombs—at least from Japanese aircraft—notwithstanding Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson’s public assertion that 15 enemy planes had overflown the city the previous night, possibly launched from secret Japanese airfields or submarines, and the Examiner’s spurious claim that 3 planes had been shot down over the ocean. After the war Japanese officials denied sending planes over Los Angeles on the night of the “Great Los Angeles Air Raid.”

|  |

Above: Civil defense sign encourages U.S. residents to hang blackout curtains in their homes and places of business and gatherings to prevent enemy pilots from seeing even a glimmer of light from where they lived, worked, and gathered (left). Setting an example, President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered blackout curtains for the 60 rooms and 20 bathrooms in the White House. A California couple (right) follows the advice of the Office of Civilian Defense, set up by Roosevelt on May 20, 1941, before the outbreak of war, and hangs black cloth over windows in their residence. Pearl Harbor jitters led to department and hardware stores being emptied of flashlights, candles, lanterns, portable radios, first-aid kits, camping stoves and the like. The urge to strike back against Imperial Japan as well as ally-in-arms Nazi Germany took hold relatively quickly, and invasion fears and hysteria among West Coast residents dissipated as the months wore on.

|  |

Left: The mammoth Sentoku, or I-400-class submarine. Difficult though it is, note the long water-tight, tube-like plane hangar on the sub’s aft deck and the forward deck’s compressed-air airplane catapult and collapsible crane for retrieving returning planes. Japanese plans called for building a fleet of 18 I‑400-class submarines, at 400 ft./122 m in length and displacing 6,670 tons, by far the largest and among the most deadly subs ever built until the 1960s. Though they could fire torpedoes (8 on board) like other submarines, the super-subs were designed as underwater aircraft carriers, each equipped with 3 Aichi M6A1 seaplane bombers. Their mission was to travel more than halfway around the world (the I‑400 had a range of over 30,000 nautical miles/55,560 kilometers and carried a crew of close to 200 men), surface off the North American coasts or the Panama Canal, and launch their deadly air attack. A generation ahead of their time, construction began on the first I‑400 at the Kure dockyard (near Hiroshima) on January 18, 1943. Only 3 Sentokus were completed; two entered service without seeing combat. An attack scheduled for August 17, 1945, on the U.S. Navy’s Ulithi Atoll staging area in the Caroline Islands of the western Pacific was scrubbed owing to Japan’s surrender 3 days earlier.

![]()

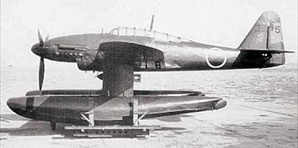

Right: A 2-man Aichi M6A1 Seiran seaplane, the type carried aboard I‑400‑class subs. The brainchild of Commander-in-Chief of the Combined Fleet Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto, the architect of the Japanese naval attack on Pearl Harbor, the I‑400‑class submarine was designed to carry 2 or 3 Seirans (which translates as “mist on a clear day”), each capable of carrying one 1,800‑lb./816‑kg bomb or torpedo for up to 739 miles/642 nautical miles. The late-war I‑400‑class class “wonder weapon” was unknown to U.S. intelligence, despite having broken the Japanese naval code.

Japan Sends Subs to Strike California, Oregon. Builds Aircraft-Carrying Super Submarines (Skip first 40 seconds)

![]()

World War II was the single most devastating and horrific event in the history of the world, causing the death of some 70 million people, reshaping the political map of the twentieth century and ushering in a new era of world history. Every day The Daily Chronicles brings you a new story from the annals of World War II with a vision to preserve the memory of those who suffered in the greatest military conflict the world has ever seen.

World War II was the single most devastating and horrific event in the history of the world, causing the death of some 70 million people, reshaping the political map of the twentieth century and ushering in a new era of world history. Every day The Daily Chronicles brings you a new story from the annals of World War II with a vision to preserve the memory of those who suffered in the greatest military conflict the world has ever seen. History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click