STALIN SNATCHES LATVIA, HITLER HALTS WAR AGAINST FRANCE

Munich, Germany • June 17, 1940

On this date in 1940 Joseph Stalin of the Soviet Union, drawing on provisions of the secret protocol in the August 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop Nonaggression Pact with his Nazi ally, ordered an attack on the Baltic state of Latvia. (The 1939 protocol had already returned dividends to the 2 conspirator nations, allowing them to divide Poland between themselves within a month of the Soviet and German foreign ministers signing the pact named after them.) The next day, June 18, 1940, an official representative of Stalin’s arrived in the Latvian capital, Riga, to assume the reins of power. The incorporation of Latvia and the other 2 Baltic nations, Lithuania and Estonia, into the constellation of Soviet socialist republics was completed in early August 1940, made all the easier after each of the Baltics had been coerced into signing mutual assistance treaties the previous September and October that allowed the stationing of large Red Army garrisons in their countries.

On the other side of the continent, Adolf Hitler, Stalin’s co-conspirator, ordered the suspension of hostilities in France on this date, June 17, 1940, and the new French premier, Marshal Philippe Pétain, took to the nation’s airwaves, informing his countrymen that negotiations for an armistice were in progress. On June 18, William Shirer, the Berlin correspondent for the American CBS radio network, stood in Paris’ famed Place de la Concorde listening to the announcement of France’s surrender over loudspeakers. Across from the Place de la Concorde on the opposite bank of the Seine the French Chamber of Deputies flew a giant swastika flag in place of the Tricolore.

The news of France’s surrender was met with enthusiasm in the ranks of the Royal Italian Army (Regio Esercito) and in Italy, which had declared war on France and Great Britain just the week before. The hostilities were over; it was time to grab the “spoils” was how Italian strongman Benito Mussolini saw it. (An Italian skirmish with French defense forces on June 21 was designed to drive the point home.) Ever the opportunist, Il Duce (Italian, “the leader”), on board a train to Munich to confer with Axis partner Hitler, generated a shopping list of materiel and territories he wanted for his country under the terms of the general armistice; for example, ships, aircraft, the island of Corsica, Tunisia in North Africa, etc.

On June 18 Mussolini and Hitler drew lines on a large military map of France that identified their future zones of occupation. They also agreed to separate armistice commissions: Hitler did not want his junior partner’s presence near the northern French city of Compiègne to intrude on the spectacular program he had choreographed for the French surrender—the armistice was to be signed in the same railway car in which the World War I Allied supreme commander, French Marshal Ferdinand Foch, had dictated peace terms to representatives of Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1918. Hitler and Germany had waited 22 years for this triumphant moment. To showcase France’s humiliation to visitors and residents of the Nazi capital, Hitler exhibited the Compiègne railway car at the foot of the steps to Berlin’s famous Altes Museum on Museum Island (Museuminsel).

Molotov-Ribbentrop Nonaggression Pact with Secret Protocol, Moscow, August 23–24, 1939

|  |

Left: Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov signs the Molotov-Ribbentrop Nonaggression Pact (aka German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact) in Moscow’s Kremlin in the wee hours of August 24, 1939. Immediately behind him is German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop and, to the German’s left, is Soviet head of state Joseph Stalin. Largely seen as Stalin’s brainchild, the pact marked the first time the Soviet dictator had been personally involved in formulating and negotiating foreign policy. As tensions between the 2 signatory nations boiled over in the first half of 1941—in April there were over 80 recorded German violations of Soviet airspace and reportedly as many as 122 German divisions just over the Soviets’ western border at the end of May—Stalin found it difficult to disavow the agreement until Hitler’s June 22 betrayal, Operation Barbarossa, forced his hands.

![]()

Right: Stalin congratulates von Ribbentrop with a warm handshake following the signing ceremony. In 1936 Hitler named von Ribbentrop ambassador to Great Britain, whom his hosts soon nicknamed “Herr von Brickendrop” due to his clumsy diplomacy at the Court of St. James. Nazi Germany’s arch-priest of National Socialism, Alfred Rosenberg, confided in his diary that Ribbentrop was a “joke of world history” for mishandling affairs in London, “put[ting] everybody’s nose out of joint.” Two years later, in February 1938, Hitler elevated Ribbentrop to head the German foreign ministry on Wilhelmstrasse, where Ribbentrop became just as despised by Berlin’s diplomatic community as he was by England’s for his arrogance and ignorance. Even Hitler’s intimates looked askance at their foreign minister. Luftwaffe chief Hermann Goering alleged Ribbentrop had only 1 genuine friend, and that was Hitler. “Is von Ribbentrop a clown or an idiot?” he wondered aloud. Nevertheless, Hitler employed Ribbentrop for the length of the war, perhaps most notoriously at the start when the foreign minister concluded the German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact days before Hitler’s Wehrmacht (armed forces) stormed over Poland’s borders to launch the most lethal conflict of the twentieth century. Rosenberg experienced a foreboding sense for what had transpired in Moscow: “I have the feeling that this Moscow pact will eventually have dire consequences for National Socialism.”

![]()

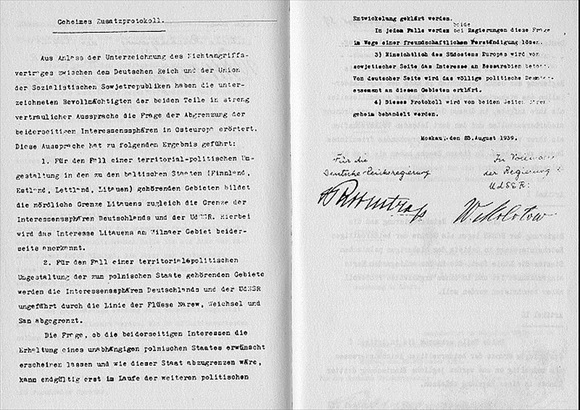

Below: The Molotov-Ribbentrop Nonaggression Pact contained a secret codicil (Geheimes Zusatzprotokoll) that was revealed only after Germany’s defeat in 1945. Under its terms Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, and Finland were to be divided into German and Soviet “spheres of influence.” Finland, Estonia, and Latvia were assigned to the Soviet sphere, as was the Romanian province of Bessarabia. Poland was to be partitioned after Hitler’s invasion of that country, which came on September 1, 1939. Thus, the western half of Poland was occupied by Germany and the eastern half of Poland came under Soviet occupation, partitioned as war booty between Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (today’s independent Belarus) and Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (today’s independent Ukraine). A second secret protocol, dated September 28, 1939, assigned the majority of Lithuania, which bordered on Germany’s East Prussia, to the Soviet Union.

|

Molotov-Ribbentrop: The Pact That Changed Europe’s Borders

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click