ROYAL NAVY DESTROYS FRENCH FLEET

Mers-el-Kébir, French Algeria • July 3, 1940

On June 22 and 23, 1940, representatives of the new French prime minister, Marshal Philippe Pétain, signed armistices with emissaries from Adolf Hitler’s Germany and Benito Mussolini’s Italy. Article 8 of the Franco-German armistice permitted the defeated French nation, headquartered after July 1 in the spa town of Vichy, to keep control of its navy. After Britain, France had the second largest force of capital ships in Europe. Pressed by Britain, the Vichy minister of the French Marine (navy), Adm. François Darlan, assured the highest levels of the British government that the demobilized and disarmed French fleet would never fall into Axis hands. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who succeeded Neville Chamberlain in office on May 10, 1940, the day Hitler’s Wehrmacht fell upon France and the Benelux countries in an undeclared war, was reminded of Chamberlain’s assertion that Hitler was “the blackest devil he had ever met.” A politician like Churchill, who at 65 had been around the political block a time or two, was not about to put any faith in a man with a history of deceit and unscrupulousness. Notwithstanding Darlan’s sacred word, the Franco-German armistice, like the infamous 1938 Munich Agreement, would doubtless be insufficient in thwarting Hitler from doing whatever he wanted; e.g., seizing French warships, arming them, manning them, and, in concert with the Italian Navy—the third largest in Western Europe—deploying them against the British in the Mediterranean Sea.

On July 2, 1940, Churchill’s War Cabinet ordered Vice Adm. James Somerville, commander of the British naval formation based in Gibraltar (Force H), to steam to the French North African port of Mers-el-Kébir and present several options to Vice Adm. Marcel Gensoul. This he did on this date, July 3, 1940, sprinting overnight with a powerful squadron that included his flagship battlecruiser HMS Hood, 2 battleships, the aircraft carrier Ark Royal, and an escort of cruisers and destroyers. One option, explained Somerville to Adm. Gensoul, was for the French fleet to put to sea with the British and continue the fight against the Germans and Italians. Another option: Be escorted to a port in the French West Indies or to a British port where French ships would be demilitarized. A third option was to disarm the ships at Mers-el-Kébir under the supervision of the Royal Navy, while a fourth was to scuttle the ships where they were. If Gensoul refused “these fair offers,” Somerville went on, he was left with no choice but to destroy the French squadron at Mers-el-Kébir.

Of course, Somerville’s options were contrary to the terms negotiated by Vichy France and her Axis victors 2 weeks earlier. Gensoul consulted the French Admiralty but in his first communication he kept the British options to himself. In his second communication he told his superiors he would defend the French fleet at the first cannon shot. Somerville delayed bombarding the French fleet until he learned that the French had dispatched naval reinforcements to Mers-el-Kébir. The British Admiralty ordered Somerville to settle matters quickly. At 5:55 p.m. Somerville gave the grim order to “open fire.”

British salvos did their worst on ships of their former military ally thanks to reports sent back from Swordfish spotter aircraft launched from the Ark Royal. French return fire was bedeviled by haze and smoke rising from burning French ships. The battleship Bretagne, whose magazine blew up, sank in 2 minutes, taking 977 French seamen to their deaths. Gensoul’s flagship, the battleship Dunkerque, hit 4 times, beached herself. The battleship Provence, hit by a 15 in./380 mm shell, was also beached. The powerful and swift battleship Strasbourg escaped the harbor just in time as 15 in. shells slammed into her vacated berth. Fifteen minutes into the bombardment Gensoul ran up the white flag and the 2 admirals struck a ceasefire.

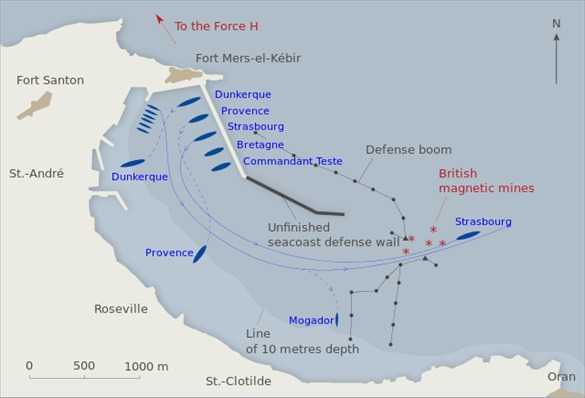

Striking Ex-Ally France: Attack on Mers-el-Kébir Harbor, July 3, 1940

|

Above: The Attack on Mers-el-Kébir is also known as the Battle of Mers-el-Kébir. The action was part of Operation Catapult, Great Britain’s painful and disagreeable naval strike launched from its western Mediterranean bastion of Gibraltar against former comrades in arms. The objects of the strike were French vessels based at Mers-el-Kébir near Oran on the northwest coast of French Algeria. The Royal Navy’s fiery bombardment killed 1,297 French servicemen and wounded 350, sank the battleship Bretagne, and damaged 5 other vessels for a British loss of 2 airmen and 5 aircraft. Elsewhere the French Navy surrendered ships in Alexandria, Egypt, and 3 submarines, 2 old battleships, and 8 destroyers in the English ports of Plymouth and Portsmouth. In Dakar, French West Africa, British aircraft attacked and severely damaged the new battleship Richelieu. In retaliation Pétain’s Vichy government ordered French warplanes to bomb Gibraltar and broke off diplomatic relations with Churchill’s government on July 5, 1940. In turn Britain recognized Free France, the government-in-exile led by Gen. Charles de Gaulle, as the legitimate government of France. Spanish dictator and Nazi sympathizer, Francisco Franco, whose country shared the same peninsula with Britain’s Gibraltar, was awed enough by the horrific Mers-el-Kébir attack and fallout to shun Hitler’s entreaties to join him and Mussolini in their Axis military pact against Great Britain.

|  |

Left: The Fairey Swordfish was a slow-moving, fabric-covered biplane torpedo bomber. Though obsolete by 1939, the Swordfish was famous for her attack on the German battleship Bismarck, which contributed to her eventual demise on May 27, 1941, in the North Atlantic. At Mers-el-Kébir Adm. Somerville sent 2 waves of Swordfish 2 hours apart to sink the fleeing Strasbourg. The swift battleship made it safely to the large French Mediterranean naval base at Toulon in southeastern France on July 4, where she met her demise when French crews scuttled her and much of the rest of the French fleet in Toulon on November 27, 1942, to prevent their falling into German hands following the Nazi takeover of Pétain’s Vichy France, precisely what Churchill had feared in 1940.![]()

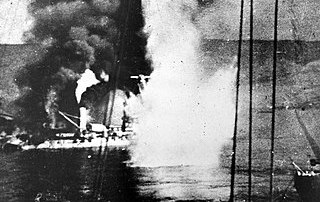

Right: The French battleship Strasbourg under fire during Operation Catapult, July 3, 1940. The Strasbourg, 3 destroyers, and 1 gunboat managed to avoid both British salvos and magnetic mines laid in an opening of the harbor defense boom and escape to open sea and the safety of Toulon.

|  |

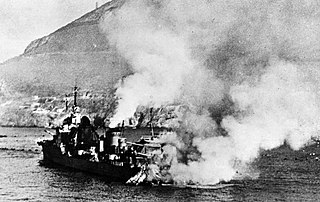

Left: Extensively overhauled at the start of 1940, the World War I battleship Bretagne burns fiercely, still under bombardment at Mers-el-Kébir, July 3, 1940. Hit 4 times by British 15 in. shells, her after magazines exploded. She rolled over and sank in 2 minutes, killing most of her crew.![]()

Right: The French destroyer Mogador running aground after her stern had been blown off by a 15 in. British shell, killing 42 seamen, Mers-el-Kébir, July 3, 1940. Badly damaged were 2 other warships: Adm. Gensoul’s Dunkerque, for a loss of 210 men, and the elderly battleship Provence. Both ships were run aground by their crews. A British Swordfish torpedo attack on the Dunkerque on July 6 did not prevent the battleship from being refloated and eventually reaching Toulon. The Provence was refloated, repaired, returned to Toulon, only to be scuttled, like the Strasbourg and the Dunkerque, by French sailors on November 27, 1942.

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click