PORT OF ANTWERP FALLS TO BRITISH 2ND ARMY

Antwerp, Belgium · September 4, 1944

Almost three months after D-Day British troops, assisted by members of the Belgian resistance, entered Antwerp on this date in 1944. They seized the Belgian port on the Scheldt River before the Germans could destroy its installations. Opening the deep-water port, whose 10 square miles of docks, 20 miles of waterfront, and 600 cranes were 80 miles from open sea, was meant to solve the “supply famine”—the logistical problems of overextended supply lines caused by the Allies’ breakneck drive to Germany. (In France, the Germans still held the ports of Calais, Boulogne, Dunkirk, and Le Harve, which in Allied hands would have gone a long way in easing supply shortages of every sort.)

Scarcely had the first Allied forces secured Antwerp, unusable due to Germans holding the Scheldt Estuary, than Adolf Hitler unleashed his hitherto secret weapon on the city—the V‑2. Flying at more than four times the speed of sound, the V‑2 ballistic missile could not be shot out of the air by aircraft or antiaircraft batteries as happened occasionally to the crude V‑1 buzz bomb (aka doodlebug) over England. With a range of 200 miles, the 46‑ft-tall, 12‑ton V‑2 impacted without warning and its 2,200 lb of lethal explosives left a giant crater on landing.

The Allies tried bombing the mobile V‑2 launch sites in occupied Holland to little effect. Next it was decided to make a northward dash, by means of a series of parachute drops deep into Holland, to overrun the launch sites that laid waste to Europe’s cities, and then cut off the Dutch coast from Germany, capture Germany’s industrial heartland (i.e., the Ruhr region, which encompassed major centers of production like Essen, Duisburg, and Duesseldorf), and make a rapid advance to Berlin, the Nazis’ nerve center. Codenamed Operation Market Garden (September 17–26, 1944), the overly ambitious and ill-planned scheme stood a minimal chance of success. Stiffer than expected German resistance helped turn the British-Canadian-American-Polish foray into a disaster. More than 6,000 of the original 35,000 airborne troops sent to seize the bridges near Arnhem on the Rhine River were taken prisoner; nearly 1,500 were killed or died from their wounds. Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, who had conceived the operation, evoked William Shakespeare’s Henry V at Agincourt, France, centuries earlier when he remarked: “In the annals of the British Army there are many glorious deeds. . . . In years to come it will be a great thing for a man to be able to say: ‘I fought at Arnhem’.” The V‑2 launch sites, never reached by the men at Arnhem, continued to rain down deadly missiles on Antwerp to the end of the war.

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”ASINList” width=”600″ height=”200″ title=”Recommended Reading” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”False” show_border=”False” asin=”1602397058,0684803305,0711033226,0982781105,0850528151,1594160120,0300134495,0965758494,0955597757,0811734862″ /]

Hitler’s Retaliation Weapons and the Destruction They Caused

|  |

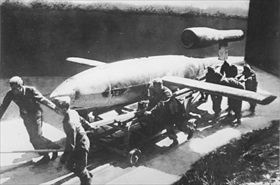

Left: Against the V‑1 threat the British deployed belts of antiaircraft batteries on the south and east coasts of England. In mid-June 1944, during their first week of deployment, AA guns destroyed 17 percent of all V‑1s entering the engagement zone. The figure rose to 74 percent in the last week of August, when 82 percent were shot down in one day. New ammunition, proximity fuses, and radar-controlled guns proved effective. Nonetheless, of roughly 10,000 V‑1s fired at England, 2,419 reached the British capital within five minutes of launch, killing 6,184 people and injuring 17,981.

![]()

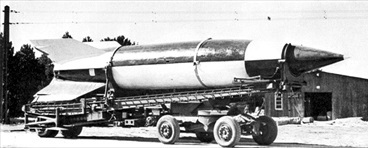

Right: The Meiller trailer (Meillerwagen), a wheeled trailer chassis and hydraulic lifting frame, was used to transport V‑2 rockets to their firing stands and to act as the service gantry for fueling and launch preparation. When vertical, the rocket was suspended above the firing stand, which was raised to touch the rocket fins. Most V‑2s were launched using mobile equipment concealed in wooded areas hidden from Allied aircraft. But the Vergeltungswaffe 2 (“Retribution Weapon 2” or “Retaliation Weapon 2”) could not win the war for Germany—the missile was too expensive, too complicated, too inaccurate, and its warhead was too small. That said, a V‑2 could create a crater 65 ft wide by 26 ft deep and eject approximately 3,000 tons of material into the air.

|  |

Left: On November 26, 1944, the first Allied shipping convoy sailed from the North Sea through the Scheldt Estuary to Antwerp’s docks after British and Canadian units had cleared the estuary of German mines, guns, and men, including 40,000 Germans taken prisoner. V‑2s continued to fall on the port city. At ten minutes past noon on November 27, as the crucial cargoes were being unloaded and moved out of the city to the Allied front, a V‑2 hit a busy intersection—Teniersplaats (Teniers Square), the geographical center of Antwerp—just as a British military convoy was passing; 157 people were killed, including 29 servicemen in the convoy.

![]()

Right: Antwerp was struck 1,610 times by V‑2s, followed by London, at 1,358. Closest runner-up was the Belgium city of Liège, at 27. This photograph shows a ruined neighborhood in East London following the explosion of the last V‑2 rocket to fall on the British capital, March 27, 1945.

V-2 Terror on Antwerp City, 1944–1945 (Some English; Flemish with English Subtitles)

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click