MARKET GARDEN, OPERATION (SEPTEMBER 1944)

| When | September 17–25, 1944 |

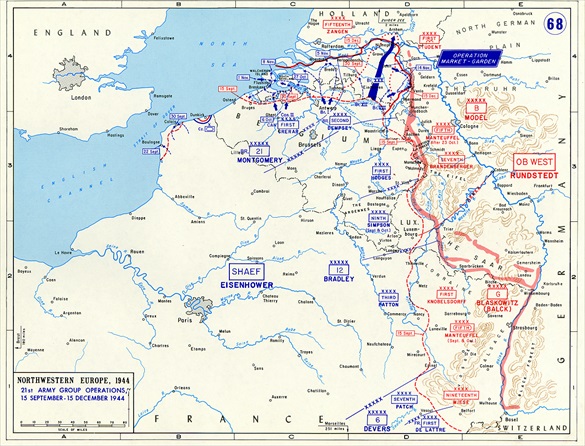

| Where | The Netherlands, near the town of Arnhem, on the Lower Rhine River, and Germany. Operation Market Garden is identified by blue arrow.

|

| Who | Allied paratroops and glider-borne infantry: The First Allied Airborne Army under the tactical command of Lt. Gen. Frederick Browning (1896–1965), made up of the British 1st Airborne Division, Maj. Gen. Robert “Roy” Urquhart (1901–1988) commanding; the Polish First Parachute Brigade, Maj. Gen. Stanislaw Sosabowski (1892–1967) commanding; the 82nd Airborne (“All American”) Division, Brig. Gen. James Gavin (1907–1990) commanding, and the American 101st Division (“Screaming Eagles”), Maj. Gen. Maxwell Taylor (1901–1987) commanding. The infantry comprised the XXX Corps, Lt. Gen. Brian Horrocks (1895–1985) commanding. Opposed by German armored and infantry units under the overall command of Field Marshal Walther Model (1891–1945) of Army Group B, which comprised the German armies in northern France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. |

| Why | The Allies wanted an all-out rapid thrust eastward over the Rhine River, bypassing major German defenses and trapping large number of German forces in the Netherlands behind Allied lines. Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery (1887–1976), who commanded the British 21st Army Group, proposed an ambitious operation to loop around the northern end of the German chain of fortifications, the formidable Siegfried Line (West Wall), consisting of artillery emplacements, minefields, bunkers, tunnels, and antitank obstacles that stretched 390 miles from the Netherlands south to the border of Switzerland. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890–1969), Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force, approved this “back-door” approach. |

| What | Complementary halves of a bold plan, Operations “Market” (airborne component) and “Garden” (armored component) were to seize strategic bridges over the Maas (Meuse River) and two arms of the Rhine (the Waal with a bridge at Nijmegen and the Lower Rhine with a bridge at Arnhem), as well as several smaller canals and tributaries. (One Allied officer, fretting that the Allies were about to overextend themselves, remarked, “I think we’re going a bridge too far.”) Capturing the Dutch bridges all at the same time would enable the Allies to establish a bridgehead behind the enemy’s main defended zone. From there huge numbers of Allied armed forces would move onto the North German Plain, then pivot southward into Germany’s industrial heartland, the Ruhr Valley. A secondary objective of the Dutch bridgehead was the possibility it afforded to neutralize V-2 launch sites around The Hague, which were bombarding London and other Allied population centers daily. |

| Market Garden was the largest airborne operation of World War II, eclipsing even those of Operation Overlord sixteen weeks earlier, delivering over 34,600 men of the 1st, 82nd, and 101st Airborne Divisions and the Polish Brigade. Additionally, 14,589 troops were landed by glider and 20,011 by parachute. Gliders also brought in 1,736 vehicles and 263 artillery pieces. Glider and parachute drop delivered 3,342 tons of ammunition and other supplies. Had it succeeded, Market Garden might have shortened the war by months, possibly before Christmas 1944. But from the start the operation was plagued by errors and miscalculations. | |

| Montgomery ignored British photo-reconnaissance as well as Dutch Resistance intelligence that two German SS panzer divisions were in the area north of Arnhem; the British airborne division was dropped six miles from its objective of Arnhem, which meant a forced march, giving the enemy time to react; the Germans retrieved a copy of the Allies’ operational order from the pilot of a downed American glider; and reinforcements and resupply were delayed by bad weather and spirited German resistance along the roads leading to the bridges. The ground advance fell behind schedule. | |

| As Allied reinforcements arrived piecemeal, they were held away from their objectives as German troops begin grinding down the British paratroopers holding the north end of the Arnhem bridge. After days of bitter fighting at great cost to both sides, the British were dislodged from the Arnhem bridge over the Lower Rhine, the “bridge too far,” as the Germans continued to advance down the road to the bridge over the Waal at Nijmegen, eight miles away. Out of the 10,000 sent into Arnhem, only 2,500 managed to make it back across the Rhine. Market Garden no longer had any chance of opening the north German plains and the industrial Ruhr Valley to the Allies. On September 25 the British evacuated the remnant of their men trapped in a small pocket west of the Arnhem bridge. | |

| Outcome | Market Garden was a risky plan, ultimately controversial, a two-pronged gamble that was variously botched from top (Montgomery owned up to mistakes he’d made) to bottom (small-unit level). In failing to breach the Rhine, Market Garden was arguably the greatest Allied defeat of the war, prolonging the war in northwestern Europe by months. German defenses had not been penetrated—they were still very much intact—and from behind them the enemy could still surprise the Allies, as they did with their Ardennes Offensive (Battle of the Bulge) that December. Consequently, the Allies were forced at enormous cost to fight their way through “the front door” of the Siegfried Line—at Remagen, Oppenheim, Rees, and Wesel—in March 1945 following Eisenhower’s broad-front strategy. German casualties in Market Garden approached 9,000 killed and wounded. Allied casualties were 17,200 killed, wounded, and taken prisoner. |

![]()

Battle of Arnhem: A Bridge Too Far

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click