JAPAN TO GARRISON FRENCH INDOCHINA

Vichy, France · September 22, 1940

As early as June 1940, after French resistance to the German conquest of France crumbled, Japan made overtures to Vichy French authorities for permission to station troops in French Indochina (now Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia) and for their warships to take up naval stations off Northern Indochinese ports. On this date, September 22, 1940, Marshal Philippe Pétain’s Vichy government agreed to allow the Japanese access to 3 airfields in the Vichy-administered colony, as well as to maintain a 6,000‑man garrison. Subsequently, from their new base in Hanoi the Japanese crossed the French Indochina border and moved north 120 miles/193 km into China, a country that had succeeded in stalemating a war imposed on them by the Japanese in mid‑1937.

Earlier the Governor-General of French Indochina, Adm. Jean Decoux (in office from 1940 to 1945), had sought Vichy French and even Western help in thwarting Japanese designs on his colony. Great Britain and the U.S., both countries with territorial holdings nearby, declined to consider military action. In a rebuke aimed at Japan, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration did ban U.S. exports of scrap iron and steel to countries outside the Western Hemisphere, with the exception of exports to Britain, effective October 16, 1940. The Japanese correctly construed the ban to be an act of economic warfare and on October 8 declared it an “unfriendly act.”

For the Japanese the September 22, 1940, agreement with Vichy France was the first physical chink in the Western powers’ protective walls in Southeast Asia and the Pacific. In January and early May 1941, Japan enlarged the hole using new agreements with Pétain. On May 6 Japan and Vichy France signed an agreement for economic cooperation in the French colony, and 3 days later Japan moved to guarantee the integrity of borders between French Indochina and its western neighbor, Thailand. Finally, on July 25, 1941, Japan was in a position to declare French Indochina a Japanese protectorate. Roosevelt retaliated by freezing $130 million in Japanese assets in the U.S. and banning oil exports to Japan. Other Western nations responded with bans and freezes of their own. Roosevelt began reinforcing military assets in U.S. Pacific outposts, unnerving Tokyo even more, which accused the U.S. of “acting like a cunning dragon seemingly asleep.” Clearly events portended more dangerous rifts between Japan and the West.

Kickoff to World War II: Japanese-Chinese Collision in China, 1937

|

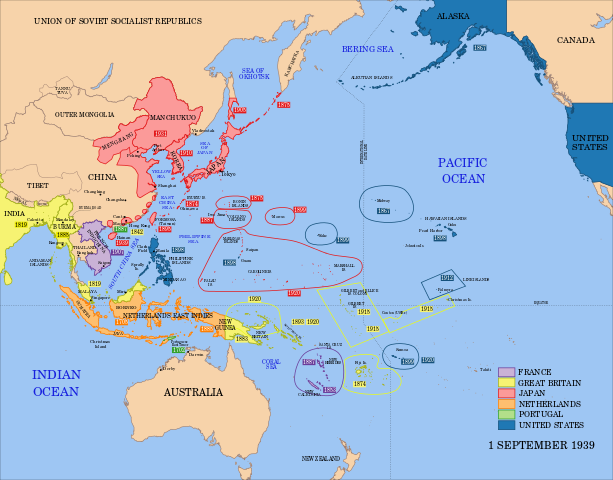

Above: Political map of Japanese, European, and U.S. possessions in the Asia Pacific region on the eve of the Pacific War. Japanese control in China was tenuous.

|  |

Left: Like other Western nations, Japan maintained a small garrison of soldiers in Peking (today’s Beijing). On maneuvers south of the city, the Japanese skirmished with Chinese troops on July 8, 1937, in the vicinity of the Marco Polo Bridge, 12 miles/19 km from Peking. It was an excuse for full-scale war. The Japanese quickly seized Peking (July 25–31, 1937) and portions of North China, and then advanced rapidly southward, placing Shanghai, South China’s industrial and economic center, under siege. Shanghai was the first of 22 major engagements between the Nationalist Chinese under their leader, Chiang Kai-shek, during the Second Sino-Japanese War (China’s War of Resistance, 1937–1945).

![]()

Right: Japanese marines landed north and south of Shanghai. This picture may have been taken on the Jiangsu coast, which is north of the city. Approximately 200,000 Chinese and 70,000 Japanese died during the Battle of Shanghai (August 13 to November 26, 1937). After the Nationalist Chinese defense in and around Shanghai crumbled, the ranking Japanese generals punished the enemy by pursuing him all the way to Nanking, the Nationalist Chinese capital.

|  |

Left: Shanghai, the world’s sixth largest city, had been a demilitarized city since 1932. The Chinese were forbidden to garrison the city, though the Japanese were permitted to maintain a few units in the city. On the eve of battle Japanese marines were headquartered near a textile mill, enjoying the company of more than 80 emplacements and bunkers of various types around them. Additionally, the Japanese Third Fleet patrolled the rivers that ran through Shanghai, and the city was well within the firing range of their guns. The Japanese anticipated a short and easy conquest of Shanghai.

![]()

Right: Japanese soldiers wearing gas masks and rubber gloves during a chemical attack in a Shanghai neighborhood. The Japanese Army frequently used chemical weapons during their 8‑year war in China. Indeed, soldiers were authorized to use chemical weapons on explicit order of their commander in chief, Emperor Hirohito himself, transmitted by the Imperial General Headquarters to Japanese commanders in China.

|  |

Left: This terrified baby was one of the few human beings left alive in Shanghai’s South Railway Station after the Japanese bombed it on August 28, 1937. Taken a few minutes after the Japanese air attack, this black-and-white photograph, titled “Bloody Saturday,” was published widely in September and October 1937 and in less than a month had been seen by more than 136 million viewers. One of the most memorable war photographs ever published, the image stimulated an outpouring of Western anger against Japanese violence in China.

![]()

Right: Japanese troops reached the destroyed North Railway Station in downtown Shanghai in October 1937. Between 1937 and 1945, the Japanese military fielded 4.1 million men and enjoyed the services of 900,000 Chinese collaborators. Facing the enemy were 5.6 million Nationalist and Communist Chinese soldiers. Of the 1,130,000 Japanese soldiers who died during World War II, 39 percent died in China. Over 10 million Chinese died from the effects of the war, with some estimates of deaths running twice as high. At least 15 million were wounded. Millions of civilians were the hapless victims of the Japanese Army’s “Three Alls Policy” (Sankō Sakusen), or scorched earth policy: “kill all, loot all, burn all.” Small wonder that the war created some 95 million refugees.

Contemporary Newsreel Footage of the Fall of Shanghai, 1937

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click