HITLER SOWS SEEDS FOR LATE-YEAR ARDENNES OFFENSIVE

Wolf’s Lair, Rastenburg, East Prussia, Germany • September 16, 1944

On this date in September 1944, at his forward headquarters in East Prussia, Adolf Hitler laid out his demands for a surprise counteroffensive on the Western Front that came to be known as the Ardennes Offensive, or Battle of the Bulge. September’s date is notable because the Allied push through liberated France to the German border was losing steam. Operation Market Garden, British Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery’s attempt to capture the Lower Rhine River crossings at Arnhem, Eindhoven, and Nijmegen in the Netherlands, ultimately failed; U.S. Lt. Gen. George S. Patton Jr.’s drive in German-held Lorraine in Northeastern France was stymied; and U.S. Lt. Gen. Courtney Hodges’ 88‑day campaign to pierce the Huertgen Forest in the Aachen sector would come up sadly short. According to Hitler’s propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, autumn’s news of Allied setbacks was enough to lift the somber spirits of a weary commander in chief who narrowly survived an attempt on his life 2 months earlier.

In his boldest move since Operation Barbarossa, Germany’s grand-scale invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1940, Hitler chose to engage both the Anglo-Canadian 21st Army Group under Montgomery and the U.S. 12th Army Group under Gen. Omar Bradley instead of striking the Red Army on Germany’s Eastern Front; at the moment he couldn’t conceive of any operational or strategic objective in the East that might weaken the Soviets’ political and military resolve to stay in the war. The Western Front was the paramount theater of operations anyway. If Germany’s armed forces could drive a wedge between the British- and American-led armies the Western alliance just might collapse. Hitler reasoned that the British, after 5 grueling years of war, would throw in the towel and leave their American friends in the lurch.

The top-ranking few in the map room when Hitler revealed his Ardennes plans expressed serious doubts. Gen. Heinz Guderian, acting chief of staff for the Army High Command (Oberkommando des Heeres, OKH) and directly responsible for military operations on the Eastern Front, urged Hitler to give priority to attacking the Soviets, now on East Prussia’s border. Col. Gen. Alfred Jodl, representing the Armed Forces High Command (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht, OKW) responsible for managing the war on the Western Front, warned of matériel shortages and the West’s aerial supremacy over the projected battle zone. Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, whom Hitler had reappointed Commander in Chief West, was “staggered,” saying later: “It was obvious to me that the available forces were far too small for such an extremely ambitious plan.” Field Marshal Walther Model, Hitler’s choice to command the Ardennes offensive, fumed: “This damned thing hasn’t got a leg to stand on.”

Still skeptical, the men in the map room dutifully lined up behind their Fuehrer. The OKW presented operational plans to Hitler in early October, and on November 10, 1944, he issued the order to prepare for the Ardennes Offensive. Strict German security and a logistics marvel delivered 406,342 men, 557 Tiger and Panther tanks, 667 tank destroyers and assault guns, 1,261 other armored fighting vehicles, and 4,224 antitank and artillery pieces to the jumping-off point on the Belgian-Luxembourg border.

All this late-year activity to the east of Allied lines drew the attention of senior commanders and intelligence agencies. Army group commanders Montgomery and Bradley professed that the “situation is such that [the enemy] cannot stage major offensive operations.” Patton, commander of the U.S. Third Army, begged to differ. Notwithstanding the Allied high command’s unworried mindset, intelligence reports continued to hint at an alarming German buildup. Photo reconnaissance reported considerable enemy activity opposite Hodges’ U.S. First Army front. And German POWs revealed that a big attack was slated the week before Christmas. At 5:30 a.m., December 16, 1944, Hitler launched his great German counterstroke, his last roll of the dice.

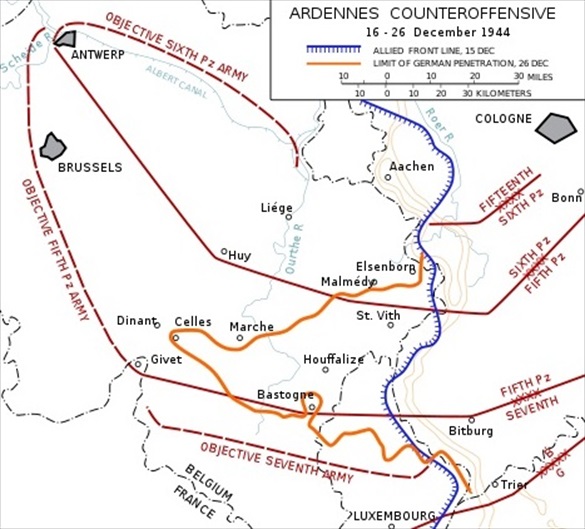

The Ardennes Offensive and the German “Bulge,” December 1944

|

Above: The German Wehrmacht (armed forces) launched a surprise attack in Belgium and Luxembourg in December 1944 in an attempt to reach the large Belgian port of Antwerp and the North Sea and thus tear open the seam between the Anglo-Canadians in Belgium and the American forces in Luxembourg and Northern France. “If Germany can deal a few heavy blows, this artificial coalition will collapse with a tremendous thunderclap,” Hitler assured his generals. For 2½ months in one of the greatest logistical feats of World War II, the generals drew on every available resource they had left—300,000 men and boys from the army (Heer), Waffen-SS (the combat branch of the Nazi Party), Luftwaffe, Kriegsmarine, Hitler Youth, and even new conscripts from prisoner-of-war camps; 970 tanks and assault guns; and 1,900 artillery pieces. This map shows the extent of the German counteroffensive that created the so-called “bulge” in Allied lines between December 16 and 26, 1944. The original German objectives are outlined in reddish dashed lines. The orangish or rust-colored line indicates the Germans’ furthest advance eastward. The German advance was stopped at the Meuse River at Dinant, shown just west of the orangish bulge.

|  |

Left: A German regiment in the bitterly cold Ardennes Forest, December 1944. Hitler selected the Ardennes for his western counteroffensive for several reasons: the terrain to the east of the Ardennes and northwest of Cologne was heavily wooded and offered cover against Allied air observation and attack during the build-up of German troops and supplies; the rugged Ardennes wedge itself required relatively few German divisions; and a speedy attack to regain the initiative in this particular area would erase the Western Allies’ ground threat to Germany’s industrialized Ruhr centered around Duesseldorf and delay their advance on Berlin. German generals were doubtful of the gambit’s success, but many younger officers and the rank and file were hopeful that an armistice on the Western Front would save their country from a disaster in the making on the country’s Eastern Front, where the Soviet Army was poised to extract their nation’s revenge.

![]()

Right: German troops advance past abandoned American equipment. The Western Allies’ string of dazzling successes in 1944, news reports of the bloody defeats that the Soviet armies were administering to the Germans on the Eastern Front, and the belief that the Wehrmacht was collapsing and the Third Reich was tottering on weak knees led Allied war planners to pay scant attention to the quiet Ardennes sector. The Americans especially paid dearly for this mindset, as well as for ignoring their own intelligence of the Ardennes counteroffensive preparations.

|  |

Left: German field commanders plan their advance through Luxembourg’s Ardennes Forest. In the Battle of Elsenborn Ridge, which lasted 10 days, the American and German lines were often confused. The main drive against Elsenborn Ridge was launched in the forests east of the twin villages of Rocherath-Krinkelt early in the morning of December 17, 1944. The attack against this boomerang-shaped piece of high ground was begun by tank and Panzergrenadiers (mechanized infantry) of the 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend. By December 27, the Germans had beaten themselves into a state of uselessness against the heavily fortified American position.

![]()

Right: Captured teenagers from the 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend. (The division took the title Hitlerjugend because it was composed mainly of young men from the Nazi Party’s paramilitary Hitler Youth organization.) Units of Gen. Leonard T. Gerow’s V Corps of the U.S. First Army held Elsenborn Ridge against the elite SS division, preventing it and attached forces from reaching the vast array of supplies near the cities of Liège and Spa in Belgium, as well as the road network west of the ridge leading to the Meuse River and the city of Antwerp. This was the only sector of the American front line during the Battle of the Bulge where the Germans failed to advance.

Contemporary U.S. Army Film of the Battle of the Bulge

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click