GERMANS UNABLE TO BREAK BASTOGNE ROADBLOCK

101st Airborne Command Post, Bastogne, Belgium • December 25, 1944

On Christmas Eve 1944 in the German-besieged Eastern Belgian town of Bastogne (population 3,500), soldiers of the armorless U.S. 101st Airborne “Screaming Eagles” Division, elements of the 9th and 10th Armored Divisions, and several combat engineer and field artillery battalions received rations of brandy and listened to the American crooner Bing Crosby sing “White Christmas” over and over and over again. Here and there makeshift Christmas trees had been decorated with tinsel by GIs using cut strips of aluminum foil intended for radar-jamming. About a hundred men attended Mass in bitter cold in front of an improvised altar lit by candles set in empty C‑ration cans. Other religious services were held as well. Soldiers manning Bastogne’s defensive perimeter wished each other a Merry Christmas, the lucky ones visited by an officer passing around sips from a liquor bottle. Outside the perimeter GIs could hear their foes signing “Stille Nacht, Heilige Nacht.” Gen. George S. Patton, Jr. pushed his foot-slogging U.S. Third Army to its limits as it toiled northward in deep snow, freezing temperatures, fog, and on icy and cratered roads to reach the German salient and rescue the Americans from what looked like a costly disaster in the making. His Christmas greetings to the besieged men: “Xmas Eve present coming up. Hold on.”

Bastogne’s stillness and darkness ended after nightfall on December 24 when a German bomber dropped magnesium flares on the town. This was followed by 2 sorties of low-flying, twin-engine Junkers Ju 88s dropping bombs that set fires to dozens of buildings and strafing streets with their machine guns. Brig. Gen. Anthony McAuliffe’s command post was hit, and the 3‑story Institut de Notre-Dame, a medical aid station, collapsed in dust and flames, killing and wounding dozens, including a score of paratroopers. The town itself had no antiaircraft defenses, the weapons having been dispatched to the perimeter.

General of Armored Troops (General der Panzertruppe) Hasso von Manteuffel of the German Fifth Panzer Army ordered the Bastogne garrison be taken on this date, December 25, 1944. The Luftwaffe’s visit the night before was simply the initial phase. The Christmas morning thrust into the town was to be provided by an armored group from the seasoned 15th Panzergrenadier Division before U.S. P‑38 fighter-bombers could take to the air. However, almost nothing went according to the enemy’s plans. Some German regiments never had time to join the battle or carry out their assigned tasks; others had not been given sufficient time to reconnoiter or coordinate with other armored units. Manning the perimeter, sharpshooting Americans piled machine-gun lead and bazooka rounds onto German tanks festooned with white-cloaked panzergrenadiers, blowing tanks and passengers to pieces or at least stunning or disabling them. Reports that German tanks were in the streets of Bastogne never arrived at Adolf Hitler’s forward headquarters at Adlerhorst (Eagle’s eyrie) in the German state of Hessen, the whys and wherefores a mystery. By early afternoon, when the 15th Panzergrenadier Division reported that it had hardly a battleworthy tank left, the Germans called off their attack, just a thousand yards/914 meters from the edge of town.

The last “desperate effort,” as a German field commander himself termed it, occurred in the morning hours of the 26th. American howitzers massed west of Bastogne literally blew a German infantry assault apart. Four German tank destroyers were brought to a halt by a large ditch and, while maneuvering, were put out of action by U.S. artillery and tank destroyer fire at close range. More bad news arrived at Hitler’s headquarters that afternoon. Following fierce village-by-village fighting in frigid temperatures, Patton’s spearhead 4th Armored Division breached the German ring around Bastogne to link up with 2 of McAuliffe’s troopers manning a roadblock a little after dusk, thereby lifting the enemy’s siege but setting the stage for even heavier fighting in the Bastogne combat sector the next month.

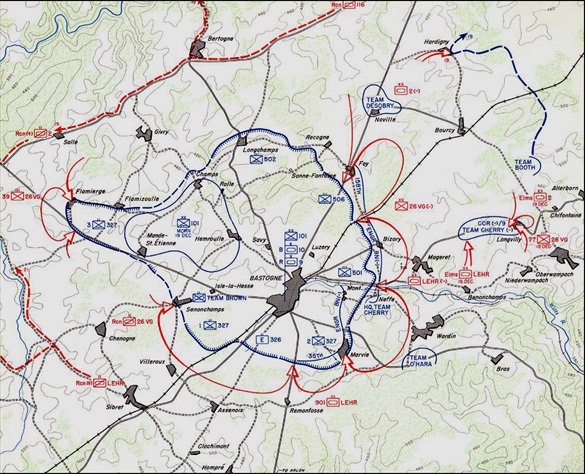

Defense of the U.S. Bastogne Garrison, December 20–27, 1944

|

Above: Control of Bastogne’s crossroads was vital to Adolf Hitler’s Ardennes Offensive (Operation Wacht am Rhein) directed at the Allies’ vital supply harbor at Antwerp, Belgium, because a railroad and 7 main highways in the Ardennes Forest converged on this small town close to the Luxembourg border. By December 20 Bastogne had become an armed camp with 4 U.S. airborne regiments, 7 battalions of artillery, a self-propelled tank destroyer battalion, and the surviving tanks, infantry, and engineers from 2 armored combat commands—all under the 101st Airborne Division’s temporary commander, peppery but genial Brig. Gen. Anthony ”Old Crock” McAuliffe, decorated veteran of Normandy (Operation Overlord) and Holland (Operation Market Garden). Inside their 30‑km/48‑mile perimeter, Bastogne’s defenders were outnumbered by the enemy 5 to 1 and lacked sufficient cold-weather gear, ammunition, medical supplies, and food.

|  |

Left: Refugees evacuate Bastogne in wagons and on foot. Confusion reigned supreme among local civilians at the onset of the siege: some people streaming in from east of town stayed to fight or provide what help they could as nurses or priests; others, realizing the roads to the west were still open, headed in that direction. Late on December 21, German troops cut the last road leading in and out of town.

![]()

Right: Around 7 p.m. on Christmas Eve, German bombers began the first of 2 aerial attacks on Bastogne, laying waste to a medical aid station, burying 20 patients in the debris, and setting fire to dozens of buildings. The Luftwaffe hammered the town again on the nights of December 29/30 in a 73‑plane raid and December 31.

|  |

Left: Paratroopers of the 101st Airborne Division watch waves of Douglas C‑47 Skytrains drop 320 tons of much needed supplies to them, Bastogne, mid-afternoon, December 26, 1944. Jeeps and trucks are parked in a large field in the near distance. The day’s airdrops were augmented by 11 Waco cargo-carrying gliders ferrying in fuel and medical personnel: 9 medical officers and enlisted technicians to assist a trauma surgeon flown in the day before. Two earlier airdrops of medicine, ammunition, and food on December 21 and 23 helped sustain the defenders, though 11 C‑47s were lost on the December 23 airdrop. Foraging parties were sent out to help alleviate shortages. ![]()

Right: 101st Airborne paratroopers retrieve containers of medical supplies from a drop zone near Bastogne during the German siege. The few doctors and enlisted medics who were left inside the siege zone had used a rapidly diminishing supply of medicine and plasma to treat the wounded who flooded Bastogne’s overcrowded aid stations. At 4:50 p.m., December 26, a battered tank battalion of Patton’s Third Army—the 37th Tank Battalion, 4th Armored Division reduced en route to Bastogne to just 3 M4 Sherman tanks and carrying a few armored infantrymen—broke the town’s siege, opening a southern supply corridor. The corridor was so narrow “you can spit across it,” an officer remarked. Fierce fighting raged for several more days but the 8‑day ordeal for McAuliffe’s brave men and the heroic townspeople of Bastogne was over.

Battle of Bastogne, December 20–27, 1944 (Skip first 15½ minutes)

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click