GERMANS POUR INTO TUNISIA AFTER TORCH LANDINGS

Tunis, Tunisia • November 9, 1942

On this date in 1942, one day after the largest amphibious invasion force in history to that time landed Allied troops on the French Algerian and Moroccan coasts, German troops, tanks, and aircraft started pouring into neighboring Tunisia from nearby bases in Italy. Operation Torch, under the command of Lt. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, saw American troops meeting relative light Axis Vichy French resistance as they made their combat debut in the North African theater of war. (The opposing Vichy colonial forces—109,000 strong—were mostly poorly armed and equipped as a result of the Franco-German armistice of June 1940, which is not to say that some well-led French forces did not fight back with everything they had, as ordered by Vichy head Marshal Philippe Pétain, particularly on the Algerian and Moroccan invasion beaches and from coastal defense guns lobbing shells on U.S. warships and transport ships offshore.)

For multiple reasons the Torch umbrella was not extended over French Tunisia. Vichy French troops surrounded Tunisian airfields and had a reasonable chance of preventing the swift buildup of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps by defending the airfields had they chosen to at an early stage. Instead, they retreated to the hills and briefly fought the Axis intruders before being beaten off by the overwhelming force they had allowed to pour into their Tunisian colony unchallenged.

The Americans’ baptism under fire occurred in rugged terrain in Western Tunisia. There Rommel’s forces momentarily halted Allied plans to push eastward and link up with Gen. Bernard Law Montgomery’s combat-tested British Eighth Army, which was advancing westward from Egypt through crumbling Axis-held Libya. The battle at Kasserine Pass, a 2‑mile/3.2‑km‑wide gap in one of the Atlas Mountains chains in West-Central Tunisia on February 22, 1943, left 6,000 American casualties. The green, poorly led U.S. Army II Corps, pitted against a blooded, experienced, well-trained, and brilliantly led Axis force, was pushed back over 50 miles/80 km from its positions in the initial days of the battle. Despite their earlier disarray, elements of the U.S. II Corps, reinforced by British reserves, rallied and held the exits through mountain passes, defeating the efforts of German and Italian forces to retake the North African offensive. Kasserine Pass was the last German offensive in North Africa, due in large part to Adolf Hitler’s fixation with restoring Nazi Germany’s fortunes in Eastern Europe following the capture and loss of the German Sixth Army (over 100,000 strong) at Stalingrad (February 1943).

Rommel, who had considered American troops a non-threat in North Africa, was devastated by the turnabout; allegedly taking medical leave, he secretly left the theater during the second week of March, 3 days after Maj. Gen. George S. Patton was placed in command of II Corps with the explicit task of improving its performance. (The secret of Rommel’s departure was so well kept that the Allies continued referring to the field marshal in their official and unofficial communications.) Rommel’s luckless replacement in Tunisia, Col. Gen. Hans-Juergen von Arnim, was captured by British Commonwealth forces on May 12, 1943, and the remaining Italians—comprising the best units of the Italian Army—surrendered the next day at Benito Mussolini’s direction. More than 275,000 Axis soldiers entered captivity, ending the Allies’ North African Campaign.

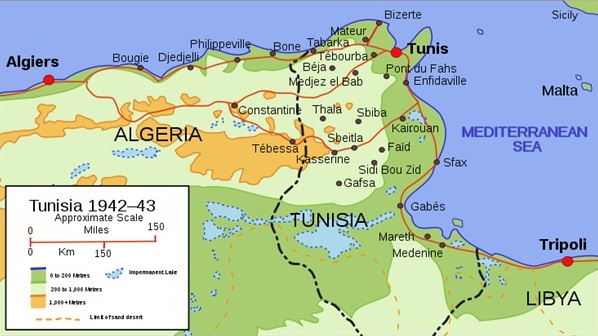

The Allied-Axis Battle for Tunisia, 1942–1943

|

Above: Sketch map of Tunisia during the 1942–1943 North African Campaign. In the weeks following simultaneous Torch landings in neighboring French Morocco and Algeria in early November 1942, the intent of the Allied command was to press the German and Italian forces in their Tunisian stronghold against the Mediterranean Sea and force their surrender. It happened but not until May 1943.

|  |

Above: In February 1943, elements of Rommel’s Afrika Korps attempted to seize Kasserine Pass, gateway to Allied-held Algeria, by a sudden, swift attack. A hodgepodge of U.S. and Free French units attempted to hold the pass. German infantry infiltrated around the defenders by climbing the heights on either side of the 2‑mile/3.2 km-wide pass. Junkers Ju 87 Stuka dive-bombers, escorted by Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighters, entered the fray. On February 20, 1943, the pass was in German hands. As the Germans continued their effort to push the Americans back into Algeria on the morning of February 22, they ran into concentrated artillery fire. On February 23, the Americans cautiously advanced eastward to discover the Germans had withdrawn. Concerned that Montgomery’s British Eighth Army might attack him in the rear while he was moving west, Rommel abandoned the battlefield and retired to the east. These photos show American units moving through the open pass.

|  |

Left: In this photograph Italian prisoners of war are seen being herded out of Tunis as the British V Corps entered the capital on May 7, 1943, the same day American armored and infantry divisions pushed the retreating Germans out of the port city of Bizerte in the north of the country. At 12:30 on May 13, one day after Mussolini had named him Field Marshal, Giovanni Messe, the Governor of Libya, surrendered the remainder of the Italian First Army. (Messe avoided von Arnim’s fate—namely, prisoner of war in the U.S. state of Mississippi—by switching loyalties and fighting on the side of the Allies against Mussolini after the Italian armistice in September 1943.)

![]()

Right: After the fall of the Tunisian port cities of Tunis and Bizerte, Axis troops began surrendering in such large numbers that they clogged roads, impeding the Allies’ mopping-up operations. In the second week of May enemy prisoners totaled over 275,000, many winding up at the Gromalia POW camp (shown here), 4 miles/6.4 km outside Tunis. When Axis generals began surrendering on May 9, 1943, the 6‑month Tunisia Campaign entered its final days. Victory in Tunisia did not come cheaply. Of 70,000 Allied casualties, the U.S. Army lost 2,715 dead, 8,978 wounded, and 6,528 missing. At the same time, however, the Army gained thousands of seasoned officers, noncommissioned officers, and troops whose experience would prove decisive in subsequent campaigns. These seasoned soldiers would not have long to wait or far to go, for the next test was only 2 months and 150 miles/241 km away, the Italian island of Sicily and Operation Husky.

The Allied-Axis Battle for Tunisia, 1942–1943

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click