GERMANS, ITALIANS HUDDLE AFTER TORCH LANDINGS

Munich, Germany • November 10, 1942

On this date in 1942, just 2 days after Allied landings in Vichy French-held Morocco and Algeria (Operation Torch), Italian dictator Benito Mussolini sent his son-in-law, foreign minister Galeazzo Ciano, to Munich in his stead to speak with Adolf Hitler. Mussolini had wanted to meet the Fuehrer in Salzburg, in the Austrian Alps, at the end of the month. But events at the top of the month in North Africa now totally consumed his attention and prevented him from leaving the Italian capital.

Meeting in the Fuehrerbau in the Bavarian capital, Ciano and Hitler, the latter looking tired and unhappy according to the Italian delegation, agreed to the immediate joint occupation of Vichy collaborator Marshal Philippe Pétain’s semi-autonomous Southern France and the Mediterranean island of Corsica (aka Vichy France or the “Free Zone”). The next month, December, at Fuehrer headquarters in Rastenburg, East Prussia, Ciano, again at the behest of an increasingly frail Mussolini, counseled Hitler to negotiate an armistice with the Soviets to avoid the decimation of German and Italian armies standing on the verge of an appalling disaster at Stalingrad. It was clear to Il Duce (Italian, “the leader”) that the war in the East could no longer be won: The Soviets had just hammered their way through a sector held by the Italian Eighth Army (Armata Italiana Russi, or ARMIR), handicapped by obsolete equipment, and the Germans blamed their Axis partner for not holding the line.

Predictably Hitler rejected Mussolini’s advice on shutting down the Eastern Front. Italian foreign ministry officials believed Hitler to be “on the edge of madness,” and the Italian embassy in Berlin went so far as to prepare a plan to “disengage” Italy and possibly other Axis members, including Romania, Bulgaria, and Hungary, from their alliance with Germany, “isolating” that country and leaving it to its own fate, but “in such a way as to preclude any accusation of treason.” Italian ministry officials did not believe Mussolini had the courage to push the plan, which was true: The Duce fired Ciano and almost all his other cabinet ministers. Mussolini assumed Ciano’s empty chair as Italy’s new foreign minister.

The next month, March 1943, Mussolini ordered the Eighth Italian Army, reduced by the carnage at Stalingrad by nearly half from the original 235,000-man force, to vacate the Eastern Front, leaving the German Wehrmacht to fight another failed operation (Operation Citadel, or Unternehmen Zitadelle, July 5–16, 1943) on their own. It was not until after the dictator himself was overthrown by the Grand Council of Fascism on July 25, several weeks after the successful Allied invasion of Sicily (Operation Husky), that a new Italian government under Marshal Pietro Badoglio could negotiate a successful switch of allegiances. For the next 4 months, the Allies clawed their way up the Italian boot, only to be stymied at Anzio (see below).

Battle of Anzio: The Drawn-Out Allied Effort to End the Stalemate in Italy, January–June 1944

|

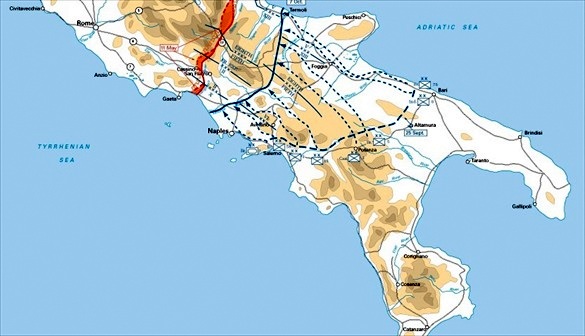

Above: After the Italian armistices of September 1943 (there were two), the Allies, with the assistance of forces loyal to the new Italian government, soon controlled most of Southern Italy—this in the face of increasing opposition from the Germans, who had thrown themselves into the battle to turn back the Allied advance up the Italian boot. On January 22, 1944, the Allies launched an amphibious invasion in the area of Anzio, 40 miles/64 km south of Rome (upper left corner of map). The invasion, codenamed Operation Shingle, was a bold plan pushed by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill to end the stalemate in Italy.

|  |

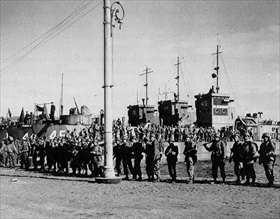

Left: Soldiers of Company A, 3rd Ranger Infantry Battalion, board landing craft that will take them to Anzio. Two weeks later nearly all would be killed or captured.

![]()

Right: U.S. Army troops landing at Anzio, late January 1944. U.S. Maj. Gen. John P. Lucas was given the task of outflanking German strong points along the Gustav (or Winter) Line (on the map, thick rust-colored line midway between Naples and Anzio) so as to enable an attack on Rome, 40 miles/64 km north of Anzio. The divisions at Anzio would link up with Allied forces farther south and break the stalemate.

|  |

Left: A Sherman tank of the 23rd Armored Brigade attached to the British Eighth Army coming ashore from a landing craft at Anzio on the first day, January 22, 1944. The Allies practically strolled ashore, taking the Germans completely by surprise. Unfortunately Lucas failed to take advantage of the element of surprise. Within 48 hours of landing, Lucas had snatched defeat from the jaws of victory by ordering his 2 divisions to dig in instead of ordering a march on Rome. A month later Lucas was replaced by his deputy corps commander, Maj. Gen. Lucian K. Truscott.

![]()

Right: German soldiers take captured Allied wounded to a first-aid station near Nettuno (not far from Anzio), March 6, 1944. German Field Marshal Albert Kesselring’s Tenth Army, which Lt. Gen. Mark Clark’s U.S. Fifth Army intelligence severely underestimated, quickly massed 10 divisions of armor and men, several of them crack combat units. Not since the Blitzkrieg of spring 1940 had Germans gathered such a large attacking force to do battle with the Western Allies.

|  |

Left: German paratroopers position an artillery piece near Nettuno. Because the Allies had failed to move inland and seize the Alban Hills, the Germans were able to look down on every part of the shallow beachhead and on the town of Anzio itself.

![]()

Right: A 4.2-in/10.66-cm mortar of 1st Infantry Brigade’s support group, firing in support of the 5th Northamptonshire Regiment in the Anzio beachhead, May 18, 1944. Several days later the regiment was on its way to Rome.

U.S. Fifth Army Report from the Anzio Beachhead, January–March 1944 (Skip the first minute)

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click