GERMAN TROOPS TAKE PARIS; FRENCH GOV’T FLEES

Paris, Occupied France · June 14, 1940

On this date in 1940 German troops marched into Paris, forcing the French government to move to Tours, then to Bordeaux, where it set up an impromptu headquarters. In a futile plea to U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the French government under Prime Minister Paul Reynaud implored the United States for a declaration of support or a declaration of war against Germany. It didn’t happen. When the majority of French ministers finally concluded that it was impossible to continue fighting against both Germany and now Italy (Italian dictator Benito Mussolini had declared war on France on June 10), the prime minister resigned. It was a stunning emotional and political collapse.

Reynaud was succeeded by 84-year-old World War I hero Marshal Philippe Pétain (1856–1951), who cobbled together a new Council of Ministers on June 16. Then, using the offices of neutral Spain, Pétain rushed to learn what Adolf Hitler required to halt military operations against his country and sign an armistice. Hitler punished Germany’s century-old enemy by waiting until June 21 to reply. After the Franco-German armistice was signed on June 22, 1940, Pétain established a new French state (L’État français) centered in Vichy, Central France. Paris remained the official French capital, to which Pétain always intended to return the government when this became possible. Civil jurisdiction of the Vichy government extended over the whole of metropolitan France except for Alsace-Lorraine, a disputed territory in Eastern France under German administration.

While officially neutral during the war, Vichy actively collaborated with the Nazis. In his capacity as head of state (Chef de l’État français, 1940–1944) and prime minister (1940–1942), Pétain suppressed Vichy’s parliament and turned his regime into a nondemocratic, repressive government aligned with, among other things, German anti-Semitic laws. French police organized raids to arrest Jews and other “undesirables” in both the northern zone, occupied by the Wehrmacht (German armed forces), and the southern, or “free,” zone (Vichy France). One of the most notorious raids occurred in Marseille in late January 1943. After the war Pétain was convicted of treason and sentenced to death, a sentence commuted to life imprisonment by his wartime enemy, Gen. Charles de Gaulle.

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”ASINList” width=”600″ height=”200″ title=”Recommended Reading” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”False” show_border=”False” asin=”0252065301,0804724997,0253008530,0199970866,1845457862,0312423594,1936274310,0199254575,0810118432,0300126018″ /]

French Jews and the Marseille Roundup, January 22–24, 1943

|  |

Left: Pithiviers internment camp was a transit camp in Pithiviers, a town in the Loire Valley, south of Paris. One-fourth of the Jews living in France were rounded up by French and sometimes German Gestapo police and deported to the death camps of Eastern Europe during the Vichy years. Few Jews in France, especially foreigners, escaped deportation and survived the war without help from courageous French men and women who willingly risked their liberty and often their lives by breaking French law.

![]()

Right: The Marseille Roundup of Jews took place in the Old Port (“Raeumung des Hafenviertels”), which the Nazis considered a “terrorist nest” because of its small, winding, and curvy streets. French police checked the identity documents of 40,000 people, nabbing 2,000 Marseillese who were passed through a series of French transit camps, eventually ending up at the Drancy internment camp outside Paris, the last stop before the death camps in the East. The Marseille Roundup also encompassed the expulsion of an entire neighborhood of 30,000 persons after a house-by-house search by German police, assisted by their French counterparts. Then the buildings were dynamited.

|  |

Left: Because of the importance the Nazis attached to the roundup of Marseille’s Jews, SS (Schutzstaffel) leader Carl Oberg, in charge of German police in France, including the Gestapo and the intelligence agency of the SS known as the Sicherheitsdienst (SD), made the trip from Paris and transmitted to René Bousquet, Vichy Secretary General of the French Police (in fur-trimmed coat with German officers, January 23, 1943), orders directly received from Gestapo chief Heinrich Himmler in Berlin.

![]()

Right: Gen. Hans-Gustav Felber (left); SS‑Sturmbannfuehrer Bernhard Griese, Commander Police Regiment Griese; and Carl Oberg at Marseille’s Gare d’Arenc freight train depot during the deportation of Jews, January 24, 1943. Oberg was the supreme authority in France for managing anti-Jewish policy and the battle against the French Resistance. He deported well over 40,000 Jews from France.

|  |

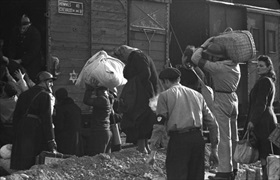

Left: Deportation in Marseille at the freight train depot Gare d’Arenc under guard of the SS Police Regiment Griese and French police, January 24, 1943. French police loaded women, children, the elderly, and the infirm into freight cars and split up families before the trains departed for transit camps.

![]()

Right: The Marseille Roundup was assisted by thugs, thieves, and murderers from the city’s underworld, who received 1,000 francs for every Jew caught, plus whatever they could steal or extort from their victims. The Nazis could also depend on French informers to maintain a steady stream of Jews to fill the deportation convoys.

Remembering the French Holocaust Through Memorials in the French Capital

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click