GERMAN TROOPS ENTER PARIS; FRENCH GOVERNMENT FLEES

Paris, Occupied France · June 14, 1940

On this date in 1940 German troops marched into a half-empty Paris, forcing the French government to move to Tours, then to Bordeaux on the French Atlantic coast, where for the third time since the Franco-Prussian war of 1870–71 it set up an impromptu national headquarters. In a futile plea on June 10 to U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the French government under Prime Minister (French, Premier ministre) Paul Reynaud implored the United States for immediate and large-scale American aid. It didn’t happen. When Reynaud and the majority of French ministers finally concluded that it was impossible to continue fighting against both Germany and now Italy (Italian dictator Benito Mussolini had declared war on France on June 10), the prime minister resigned. It was a stunning military, political, emotional, and soon-to-be moral collapse.

The anti-Nazi Reynaud was succeeded by 84-year-old World War I hero Marshal Philippe Pétain (1856–1951), vice president of the Council of Ministers who cobbled together a new governing council on June 16, just over 5 weeks after Adolf Hitler’s Wehrmacht (German armed forces) attacked France and the Benelux countries simultaneously. The next day, using the offices of neutral Spain where he had served as France’s ambassador in 1939–1940, Pétain rushed to learn what Hitler required to halt military operations against his country and sign an armistice. Ninety-five percent of the public supported Pétain’s efforts. He was hailed as a male Joan of Arc, saving his countrymen from the “abyss.” Frenchmen cheered his radio address of June 17 when he declared immodestly that he was “giving to France the gift of my person in order to alleviate her suffering.” On June 18 in Paris’s Place de la Concorde, one of the city’s major public squares, loudspeakers announced France’s surrender. On the left bank of the Seine, across from the Place de la Concorde, a giant swastika flag already flew above the French Chamber of Deputies, and in front of the Ministry of Marine a Mark IV Panzer tank was parked.

Hitler punished Germany’s century-old enemy by first waiting until June 21 to reply to Pétain and then summoning the French peace delegation to the woods of Compiègne, the very location where Kaiser Wilhelm’s Germany had surrendered to the victorious Allies not 22 years earlier. After the Franco-German Armistice of Compiègne was signed on June 22, 1940, which ended the Third Republic, Pétain established a new French state (L’État français) centered in Vichy, a spa town in Central France. Paris remained the official French capital, to which Pétain always intended to return the government when this became possible. Civil jurisdiction of the Vichy government extended over the whole of metropolitan France except for Alsace-Lorraine, a disputed territory in Eastern France now under German administration.

While officially neutral during the war, Vichy actively collaborated with the Nazis. In his capacity as head of state (Chef de l’État français, 1940–1944) and prime minister (1940–1942), Pétain suppressed Vichy’s parliament and turned his regime into an anti-democratic, anti-liberal, repressive government aligned with, among other things, German anti-Semitic laws. The 60,000‑strong Gendarmerie (French police) organized raids to arrest Jews and other “undesirables” in both the northern zone, occupied by the Wehrmacht, and the southern, or “free,” zone (Vichy France). One of the most notorious raids occurred in Vichy’s Mediterranean port of Marseille in late January 1943 (see photo essay below). After the war Pétain was convicted of treason and sentenced to death following a three-week trial, a sentence immediately commuted to life imprisonment by his prewar subordinate and wartime enemy, Gen. Charles de Gaulle.

French Jews and the Marseille Roundup, January 22–24, 1943

|  |

Left: Pithiviers internment camp was a Vichy-managed transit camp in Pithiviers, a town in the Loire Valley, 50 miles south of Paris. One-fourth of the 330,000 Jews living in France at the start of the war were rounded up by French and sometimes German Gestapo police and deported to the death camps of Eastern Europe during the Vichy years. Few Jews in France, especially foreign-born, escaped deportation and survived the war without help from courageous French men and women who willingly risked their liberty and often their lives by breaking French law.

![]()

Right: The Marseille Roundup of Jews was conducted by some 12,000 French police from various forces and about 5,000 Germans. The roundup took place in the Old Port (Vieux Port), which the Nazis considered a “terrorist nest” because of its small, winding, and curvy streets and ancient hidden underground passageways. French police checked the identity documents of 40,000 people, nabbing 2,000 Marseillese who were passed through a series of French transit camps, eventually ending up at the Drancy internment camp, a disused housing estate on the outskirts of Paris, the last stop before the death camps in the East. The Marseille Roundup also encompassed the expulsion of an entire neighborhood of 30,000 persons after a house-by-house search by German police, assisted by their French counterparts. Then the buildings were dynamited. In all, 2,000 structures spread over 35 acres were reduced in 17 days to a wasteland of rubble and dust.

|  |

Left: German-Vichy French meeting in Marseille’s hôtel de ville (city hall), January 23, 1943. Along with Lyon, Marseille had the highest population of Jews (35,000) in Vichy France. Because of the importance the Germans attached to the roundup of Marseille’s Jews, SS (Schutzstaffel) General Carl Oberg, in charge of German police in France, including the Gestapo and the intelligence agency of the SS known as the Sicherheitsdienst (SD), made the trip from Paris and transmitted to René Bousquet, Vichy Secretary General of the French National Police (smiling in fur-trimmed coat and tie with German officers), orders directly received from Gestapo chief Heinrich Himmler in Berlin. After Pierre Laval, Vichy prime minister in the Pétain government, Bousquet was the person most culpable for the deportation of 50 percent of the pre-war French and foreign Jewish population who were murdered in Nazi extermination camps in the East.

![]()

Right: Gen. Hans-Gustav Felber (left); SS-Sturmbannfuehrer Bernhard Griese, Commander Police Regiment Griese (facing camera); and Carl Oberg at Marseille’s Gare d’Arenc freight train depot during the deportation of Jews, January 24, 1943. Oberg was the supreme authority in France for managing anti-Jewish policy and the battle against the French Resistance. Before moving to France, Oberg was the former personal adjutant to SS Obergruppenfuehrer Reinhard Heydrich, the leading planner of the “Final Solution of the Jewish Question” (German, Endloesung der Judenfrage), the annihilation of European Jewry. Oberg deported well over 40,000 Jews from France—men, women, and, as a “humanitarian” measure to keep families together, children.

|  |

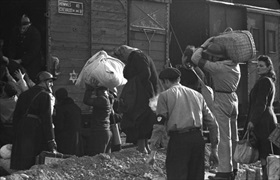

Left: Deportation in Marseille at the freight train depot Gare d’Arenc under guard of the SS Police Regiment Griese and French police, January 24, 1943. French police loaded women, children, the elderly, and the infirm into freight cars and split up families before the trains departed for transit camps.

![]()

Right: The Marseille Roundup was assisted by thugs, thieves, and murderers from the city’s underworld, who received 1,000 francs for every Jew caught, plus whatever they could steal or extort from their victims. The Nazis could also depend on French informers to maintain a steady stream of Jews to fill the deportation convoys.

Remembering the French Holocaust Through Memorials in the French Capital

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click