FRANCE BEGINS TO EMPTY ITSELF OF JEWS

Paris, Occupied France • March 27, 1942

On May 10, 1940, Adolf Hitler, having ended Poland’s existence in September 1939, turned his wrath on the democracies in the West. The Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg capitulated to his war machine in May. Representatives of 84‑year-old Marshal Philippe Pétain, who had recently been named president of the Council of Ministers of the French Third Republic, signed a ceasefire with Hitler on June 22, 1940. Hitler could not have made the armistice ceremony any more humiliating for the French, occurring as it did in the same railway car at Compiègne in Northern France where Kaiser Wilhelm II’s delegates had signed the World War I armistice.

Early in October 1940 Marshal Pétain’s new collaborationist Vichy government—named after the resort community in Central France in which his administration had settled—approved the first of 26 French anti-Semitic laws, Statuts des Juifs. The laws, together with 30 decrees published through September 1941, affected over 300,000 self-identified Jews in France, of which 200,000 lived in Paris and its environs. Similar anti-Semitic laws were quickly approved in the Vichy North African possessions of Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia. Passed largely unopposed and without coercion from German authorities, the French defined Jewishness in more encompassing terms than did the Nazis’ infamous Nuremberg Laws of the 1930s, and like the Nuremberg Laws the Statuts des Juifs deprived French Jews of the right to hold public office or serve in the military, regulated their membership in the medical and legal professions, and deprived them of normal French citizenship. Naturalized French citizens had their papers revoked, thereby rendering them stateless. By the end of October 150,000 Jews had obediently registered with the Parisian police (registration, it turned out, was preliminary to rounding up the Jews), and Jewish businesses complied with the law that required them to place bilingual signs in their windows identifying them as Jewish owned.

Arrests of Jews in Paris began in May 1941, 1½ months after Vichy created the Commissariat Général aux Questions Juives to coordinate repression of Jews in both the German military zone in the north and west of France (zone occupée) and the Vichy-administered central and southcentral part of France, the so-called “Free Zone” (zone libre). In the summer of 1941 the chasse aux Juifs, the hunt for Jews, began in earnest, so zealously pursued by French collaborators and anti-Semites (France had a long history of anti-Semitism) that even cynical Nazis were said to be impressed. Municipal police, the Milice française (a right-wing paramilitary militia nominally headed by Vichy’s Prime Minister and Minister of the Interior, Pierre Laval), and the French Self-Defense Corps, the latter 2 organizations largely manned by native Fascist thugs and, in the case of the Milice, released jailbirds, all did the bidding of Germans to round up French Jews for eventual deportation to Nazi Germany. Their initial target: the Jews of Paris. Hardest hit were arrondissements (administrative districts) that brimmed with Jewish establishments and families, many foreign-born refugees or poor. Searched right down to their genitals in the case of males, their victims were taken to the newly opened internment camp of Drancy on the outskirts of Paris, others to camps at Compiègne, Pithiviers, and Beaune-la-Rolande. In all, there were over 200 internment camps in France and its overseas possessions.

On this date, March 27, 1942, 1,112 Jews, the first of between 75,500 and 76,000 Jews residing in France (two-thirds of whom were foreign-born), were placed in third-class railroad cars with seats (later into cattle cars each holding 80–100 people) provided by the French state railway system, SNCF. Their destination: Nazi death factories in the East—chiefly Auschwitz-Birkenau—where the great majority of them would be systematically exterminated. Fewer than 3,000 of these deportees returned alive.

![]()

The French “Hunt for Jews” (“Chasse aux Juifs”), Paris, 1941–1942

|  |

Left: Shortly after the German occupation of France in June 1940, the reactionary, collaborationist Vichy administration of Marshal Philippe Pétain, encouraged by occupation authorities, began a program of registering all 330,000 Jews in France; only half were French nationals. This photo shows officials carefully examining the identity cards of Parisians suddenly stopped at a sidewalk table. For those carrying a false carte d’identite (the country was flooded them), it was important for such people to carry all kinds of supporting papers—“plausibility papers” they were called—the more varied the better: social security cards, student IDs, driver’s licenses, certificates of employment, traffic fines, library cards, trade union cards, ration cards, military service records and the like. Many Jewish Parisians easily “passed” for Aryans (non-Jewish Caucasians). Occasionally encountering public disdain or harassment, they and other law-abiding Jews sometimes felt uncomfortable, even humiliated being forced to wear the yellow Star of David on the left side of their outermost garment, as legislated in late May 1942 for Jews age 6 and over. As for the identity card, depending on the sex of a person a Jew’s card bore an official red stamp in bold that read “JUIF” or “JUIVE.” Fake cards carried no such stamp.

![]()

Right: A prewar 4-story low-income housing complex built in the shape of a horseshoe, the Drancy internment camp northeast of Paris was an interrogation, detention, and assembly camp, mainly for Jews, but also for communists, Gaullists, Freemasons, human smugglers (passeurs), Jewish sympathizers, and other “enemies” of the Vichy government. Barbed wire, searchlights, machine guns, and police sentinels ringed the camp. Dormitories designed for 30 people housed 4 times that number. The fortunate slept 3 to a bunk, the rest on straw-covered floors. In mid-July 1942, when French authorities launched a massive arrest of Jews in Paris, codenamed Opération Vent printanier (Operation Spring Breeze), police brought the first 13,000 of their victims, among them 4,501 children and 5,802 women, to the Vélodrome d’Hiver (Winter Velodrome), a massive indoor cycling stadium known by locals as the Vel d’Hiv, a stone’s throw from the Eiffel tower. (The July roundup by roughly 4,500 French policemen is commonly called the Rafle du Vel’ d’Hiv or La Grande Rafle, the Big Roundup. The infamous sweep necessitated importing young provincial policemen to bolster the work of the pitiless Paris police.) Five days later the police hauled the detainees, famished and dehydrated, to Drancy, Beaune-la-Rolande, and Pithiviers internment camps near Paris.

|  |

Left: French police arrest Jews in Paris and place them on 1 of the city’s green-and-cream municipal buses for transport to a Vichy internment camp for registration and interrogation. The largest camp, Drancy, together with its 5 subcamps, first fell under French police administration. Early in July 1943 the camps became the responsibility of the German secret police, the Gestapo Office of Jewish Affairs in France.

![]()

Right: Busloads of Jews arrive at Drancy internment camp in this photograph from August 1941, the month when, on German orders, Paris police conducted their second rafle (roundup) of Jews, some 4,300. The first Paris rafle, on May 14, 1941, had swept up about 4,000 Jewish men, mostly Polish immigrants. A third Parisian roundup occurred in December and was the first and only time Germans took the lead. French police, strictly monitored by Vichy’s sinister and brutally anti-Semitic Commissariat Général aux Questions Juives, conducted more than 90 percent of the arrests of Jews during the Occupation. Police went so far as to arrest some Jewish children in their nurseries, kindergartens, and classrooms. Other children were simply abandoned to the streets, penniless, after police had arrested their parents and hauled them away.

|  |

Left: Wearing dark blue kepis French police process their Jewish hostages. The German Army set up internment camps to hold Allied civilians captured in areas it occupied in France. Civilians included U.S. citizens caught in Europe by surprise when Hitler declared war on America in December 1941, as well as British Commonwealth citizens caught in areas engulfed by the Blitzkrieg in the West.

![]()

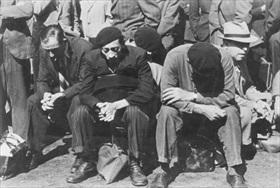

Right: Traumatized Jews await an unknown fate. Could any of them have predicted what Hitler had in store for them at this point in time? Not until June 2 and June 26, 1942, did European listeners to BBC radio broadcasts hear dreadful reports from Polish underground sources describing the murder of 700,000 Jews in German death camps in the East. But could these reports be credible? Between June 22, 1942, and the end of July 1944, 67,400 French, Polish, and German Jews were deported from France in 64 rail transports (convois), mainly to Auschwitz but some to Sobibór, both extermination camps in Nazi-occupied Poland. Among them were 11,000 children, some less than 2 years old, including infants only days old. (Cruelly, children were required to leave their beloved toys behind.) People over 60 numbered 9,000. The oldest was a 95‑year-old woman. At Paris’s Drancy internment camp just 1,542 internees remained alive when Allied forces liberated it on August 17, 1944. Also in Paris, 40,000 Jews survived to witness the expulsion of the German Occupier, thanks in many cases to the support of sympathetic and courageous Gentiles and even Jewish acquaintances, others to sheer luck, savvy, forged documents, and bribes. A particularly courageous Gentile living in Nazi-occupied France, Aristides de Sousa Mendes, the Portuguese consul in Bordeaux, defied his government and issued some 30,000 visas, including about 10,000 to Jews, that allowed visa holders to reach the safety of Lisbon and points beyond.

Vichy French Newsreels from the Early 1940s. Includes Marshal Pétain Addressing Nation

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click