ALLIES OPEN UP SECOND FRENCH FRONT

Côte d’Azur on the French Mediterranean • August 15, 1944

The Allied assault on German-occupied Southern France originally was to have kicked off simultaneously with the Allies’ June 6, 1944, invasion of Northwestern France (Operation Overlord)—the intent being that the Germans would think twice before sending reinforcements from Southern France to the Normandy beachheads and that, with any luck, the enemy would be trapped between 2 invading Allied armies in a classic pincer movement. However, a worldwide shortage of sufficient landing craft, together with Overlord planners upping the number of participating divisions in the Normandy invasion from 3 to 5, forced Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander, to extend the start date for Operation Anvil, renamed Operation Dragoon, by 6 weeks.

On this date, August 15, 1944, the Allied invasion of Marshal Philippe Pétain’s Vichy France began with a parachute jump of 9,000 U.S. and British infantrymen. (Late the night before and into the next day commandos of First Special Service Force neutralized German coastal defense batteries opposite the Allied landing areas and sea lanes.) The jump by the 1st Airborne Task Force, which secured the area northwest of the landing beaches, was quickly followed by an aerial bombardment by the first set of 1,300 Allied bombers, a naval bombardment, glider landings, and an amphibious assault by a mixed force of Americans and Frenchmen. Within hours of the landings, the invasion force (troops, vehicles, and tanks) was twice the size in men alone of the opposing German Army Group G, which was poorly equipped, stretched too thin, and woefully understrength. (There was only 1 army, the 19th, in Army Group G!) Many of the German defenders were either older Wehrmacht (armed forces) replacements or Central and Eastern European Volksdeutsche (ethnic Germans) and Ostlegionen (foreign legion-types). With few exceptions German resistance to the Allied invasion was negligible. Many defenders, especially non-German servicemen, quickly surrendered.

After nightfall on August 16/17 Army Group G headquarters realized the impossibility of its land (83,000–100,000 in the assault zone), naval (45 small ships), and air (200 aircraft) forces ever expelling the Allies from their Mediterranean lodgment. By then Allied units had penetrated 20 miles/32 kilometers inland in some sectors. The defenders therefore decided to sacrifice the port cities and their garrisons at Toulon (liberated by a mixed force of U.S. and French soldiers on August 27 with a loss of 17,000 German POWs) and Marseille (mostly liberated by August 27 with a loss of 11,000 POWs) to buy time for a fighting withdrawal up the Rhône River valley. However, in both Toulon and Marseille German demolition engineers succeeded in rendering the port facilities momentarily useless.

Pursuing the enemy continued as one Rhône town and city after another fell (Lyon, Dijon), and in a timespan of 40 days most of France had been liberated. On September 10 Dragoon units were able to establish contact with units from Gen. George S. Patton’s U.S. Third Army. Slowing almost to a crawl due to overstretched Allied supply lines from the coast of Southern France, the pursuit of the enemy ended later in the month when Army Group G—reduced by half now—reached the sanctuary of the Vosges Mountains near the French frontier, leaving more than 130,000 German troops trapped behind Allied lines, 7,000 dead on the battlefield, and 20,000 wounded. Eventually, the southern route opened by Operation Dragoon became a significant source of supplies for the Allied advance into Germany, providing between 30 and 40 percent of the total Allied requirement.

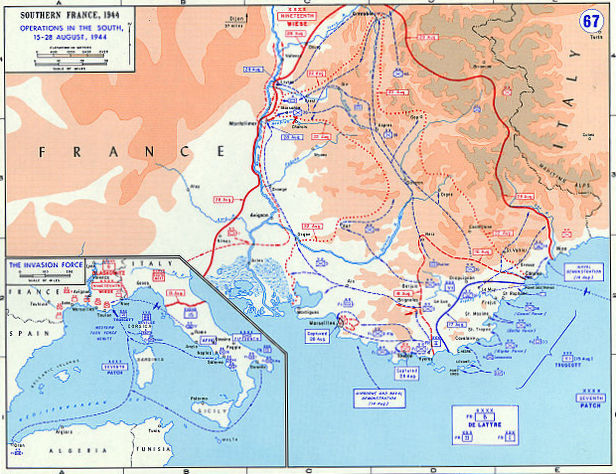

Operation Dragoon: The Allied Liberation of Southern France, August–September 1944

|

Above: Over the course of the monthlong southern offensive (August 15 to September 14, 1944), the Allies drove 400 miles/644 kilometers northward into France, liberating 10,000 square miles/25,900 square kilometers of territory while inflicting 143,250 German casualties. Launched with reluctant British participation, Operation Dragoon provided crucial support to the main Allied thrust into Nazi Germany across the Rhine. Dragoon remains one of the most successful air-land-sea operations of the war, although it has been overshadowed by the larger operation in the north of France, Operation Overlord, the Allied invasion of Normandy 2 months earlier.

|  |

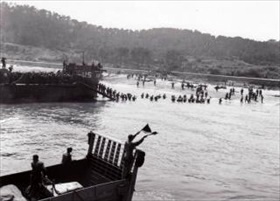

Left: Men of the 45th Infantry Division land at Sainte Maxime, situated in the middle of Operation Dragoon’s 5 invasion beaches, August 15, 1944. The 45th Infantry Division was 1 of 3 assault divisions (the other two were the 3rd and 36th) to land on the French Riviera (Côte d’Azur). The 3 divisions were part of VI Corps coming under Gen. Alexander (“Sandy”) Patch’s U.S. Seventh Army.

![]()

Right: Members of the 30th Infantry, 3rd Infantry Division board ten LCIs (Landing Ships, Infantry) and one LST (Landing Ship, Tank), July 24, 1944, near Naples, Italy, for a practice landing in anticipation of the upcoming invasion of Southern France.

|  |

Left: 3rd Infantry Division disembarking from LCI 188 at Cavalaire-sur-Mer, between Toulon and Italy, August 15, 1944. The 3rd Infantry Division was one of the few U.S. Army divisions that fought on all European fronts, seeing combat in North Africa, Sicily, Italy (Salerno, Cassino, and Anzio), France (Rhône Valley, Vosges Mountains, and Strasbourg), Germany (Nuremberg, Augsburg, and Munich), and Austria for 531 consecutive days.

![]()

Right: Capable of carrying 150 tons, the LCT (Landing Craft, Tank) in this photo is shown unloading tanks and tank destroyers for the 36th Infantry Division at Saint-Raphaël, the easternmost invasion beach, August 15, 1944. The division encountered only light opposition in their landing sector. The 36th’s rapid advance opened up the Rhône River Valley.

Operation Dragoon: Allied Invasion of Southern France

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click