VATICAN SIGNS PACT WITH NAZIS

Rome, Italy · July 20, 1933

On this date in 1933 in Rome, representatives of German President Paul von Hindenburg and Pope Pius XI (1922–1939), among them Vatican Secretary of State Eugenio Pacelli (later Pope Pius XII), announced that a concordat (treaty) had been forged between the Holy See and the German Reich. The Reichskonkordat was a major propaganda coup for the Nazis, in power nearly six months. It gave the impression that the Nazi regime of German Chancellor Adolf Hitler, who had acquired quasi-dictatorial powers through the Enabling Act of March 23, 1933, posed no threat to German churches, notwithstanding the ominous opening lines in the concordat that stated relations between the two entities must be regulated “in a way acceptable to both parties.” Within the week Pacelli, the chief author of the concordat, was forced to defend the Holy See in the first of two articles in the Vatican’s newspaper, L’Osservatore Romano. Soon after ratification the Vatican began reporting breaches of the concordat. Catholic critics within Germany were forced to mute their responses to the state’s interference in religious matters and to misdeeds Nazi radicals committed against the Church and its organizations. In time the Holy See issued the papal encyclical Mit Brennender Sorge (“With Burning Concern”). Written in German, not the usual Latin, it was read in all German Catholic churches on Palm Sunday 1937, a day when church attendance was highest. Pius XI’s encyclical condemned the paganism of Nazi ideology, the myth of race and blood, and the bastardized Nazi conception of God. It warned Catholics that the growing Nazi ideology, which exalted one race over all others, was incompatible with Catholicism. Over 300,000 copies were circulated. The day after Palm Sunday, Gestapo bullies raided church offices and seized every copy they could lay their hands on. Privately Pacelli fumed over “the actions of the German Government at home, their persecution of the Jews, their proceeding against political opponents, [and] the reign of terror to which the whole nation [is] subjected”—this to the British ambassador to Rome. With the exception of Pius XI’s 1937 encyclical, the Holy See’s differences with Nazi Germany were generally not aired in public. Some historians have characterized Pacelli (Pius XII) and his papacy as having an “ambiguous record” and responding weakly to the Holocaust.

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”ASINList” width=”600″ height=”200″ title=”Recommended Reading” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”False” show_border=”False” asin=”0253214718,0800629310,0813220165,081321081X,087580330X,0312604211,0674049616,014311400X,0895260344,1592765653″ /]

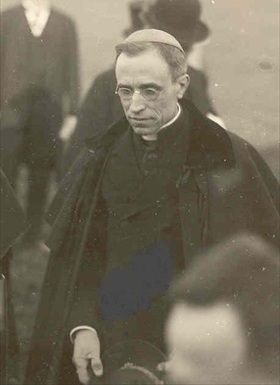

Eugenio Marìa Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli (Pius XII), 1876–1958

|

Above: Vatican Secretary of State Eugenio Pacelli (seated, center) at the signing of the Reichskonkordat on July 20, 1933, in Rome. Seated to Pacelli’s right is German Vice-Chancellor Franz von Papen. Between 1933 and 1939 Pacelli issued dozens of protest violations of the Reichskonkordat, which at the outset he had hoped would protect the rights of Catholics under the new German government of Adolf Hitler. Pacelli’s actions as secretary of state and later as Pope Pius XII have generated controversy, particularly on the subject of the Holocaust. An entire library of books has been built either defending Pius XII’s papacy or taking him to task (the “Pius Wars”). His detractors have accused him of everything from anti-Semitism to colluding with the Nazis (“Hitler’s pope”). Others claim the Catholic Church did more than any other religious body to save Jewish lives, occasionally through Pius XII’s personal intervention; e.g., Pius instructed papal diplomats to aid persecuted Jews in Nazi-occupied nations, he contributed money to aid desperate Jews, he opened Catholic facilities in the Vatican and in other parts of Rome and Italy to shelter thousands of Jews from the Nazis, and he gave direct face-to-face orders to protect Jews from the Nazis. In the end, with Pius XII’s help a remarkable four-fifths of the Jewish population of Catholic Italy escaped Hitler’s Final Solution.

|  |

Left: Pacelli, Apostolic Nuncio (ambassador) to Bavaria (1917–1925), pays a visit to a group of bishops in 1922. Pacelli was simultaneously Apostolic Nuncio to Germany (1920–1930).

![]()

Right: Pope Pius XII on his day of coronation, March 12, 1939. Pacelli (1876–1958) took the same papal name as his predecessor, a title used exclusively by Italian popes. When Pacelli was elected pope, the Nazi regime registered strong protests and called Pius XII the “Jewish Pope” because of his earlier condemnation of German race laws when he was Vatican secretary of state.

Coronation of Pope Pius XII (in Italian), March 12, 1939

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click