U.S. WAKE ISLAND DEFENDERS REBUFF INITIAL JAPANESE INVASION

Wake Island, Central Pacific Ocean • December 11, 1941

As war clouds gathered over the Western and Central Pacific in the late 1930s/early 1940s, U.S. military brass identified a V‑shaped set of coral islets, since 1899 an American outpost between Hawaii and Guam, a “priority defense requirement.” Actually a submerged volcano top, Wake Island (see map below) happened to be one of the loneliest atolls in the entire Pacific. Yet by 1935 the tiny wasteland of sand, scrubby trees, and brush had emerged as an important commercial and military airbase. Between early 1941 and August 19 civilian contractors and 178 Marines landed on Wake to improve the island’s feeble defenses and build an air station and barracks for U.S. naval and Marine personnel.

On October 12, 1941, Major James Devereux arrived with Marine reinforcements and more civilian construction workers. The balding, 38‑year-old Marine embraced his task with a fury. Overworked Marines and civilians scrambled round-the-clock to build out the naval base as well as the coral runway for U.S. Army Air Corps B‑17 Flying Fortresses that soon would be landing there. Six 5 in./127 mm coastal defense guns were dispersed over the islets.

In December 1941 the Wake Island garrison numbered 422 Marine enlisted men (mostly artillerymen) and 27 officers of the 1st Defense Battalion under Maj. Devereux, as well as Marine aviators of Marine Fighting Squadron (VMF) 211; 10 naval officers and 58 enlisted men (including hospital corpsmen); a 5‑person Army communications unit; 70 Pan American Airways civilians and 1,146 contractor employees. Apart from Oahu, Hawaii, Wake had become the most heavily defended U.S. island outpost in the Central Pacific. That said, significant defense deficits remained: a desperately needed radar system never arrived to give advance warning of an enemy attack (a weakness the Japanese would exploit), and reinforcements to the Navy’s air arm, consisting of 12 Grumman F4F‑3 Wildcat fighters minus instruction manuals and spare parts, arrived just 4 days before war broke out.

At noon on December 8, 1941 (December 7 in Pearl Harbor), Japanese twin-engine bombers and fighter aircraft, using a rain squall and low cloud cover to fly unseen and unheard, launched a deadly strike on the American base. In quick order the bombers destroyed 8 Wildcat fighters on the ground (4 were in the air), blasted gasoline storage tanks, and killed and wounded 34 Marine aviation personnel. On this date 3 days later, December 11, a Japanese special naval invasion force arrived and received a drubbing. Marine shore batteries and the remaining Wildcats caused the deaths of at least 200 to 340 Japanese (sources vary), injuries to 65, and the loss of 2 destroyers (a first for Japan). The invaders—450 Special Naval Landing Force troops in transports and old destroyers—never set foot on the island. Amazingly only 1 American perished in this first battle between U.S. Marines and Imperial Japanese forces. However, Wake’s air cover was now practically nonexistent: just 2 Wildcats remained in working order. (The fighters were later destroyed in combat.) Defiant and proud, the Marines knew the Japanese would attempt a second landing.

On December 23 the Japanese did just that. In between, however, Japanese aviators left daily explosive calling cards. It was hair raising, bone rattling, and mind numbing for the garrison’s anxious defenders. A U.S. Navy relief expedition centered on the aircraft carrier Saratoga departed Pearl Harbor on December 12, but it was recalled 10 days later, 2 days out from Wake Island and 1 day after Japanese soldiers had overrun the tiny island. Marines and civilian construction workers died amid a hail of bullets and grenades, some grappling their attackers in brutal hand-to-hand combat. The survivors—400 Marine, 5 Army and 65 Navy personnel, and 1,076 civilians—were taken prisoner. Most were transported by sea to Japanese POW camps for slave labor, but over 100 civilian contractors were retained as workers on Japanese-occupied Wake. On October 7, 1943, the island’s remaining Americans were bound, blindfolded, led to the beach, and machine-gunned to death by their captors.

Battle of Wake Island: U.S. Marines’ Legendary Last Stand, December 8–23, 1941

|

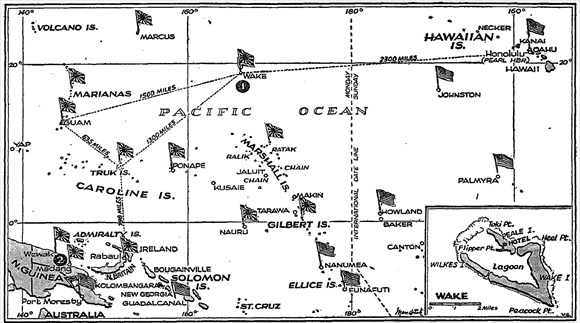

Above: Map of the Western and Central Pacific Ocean, circa early 1943. Japanese-occupied Wake Island atoll (Wake Island, Wilkes Island, and Peale Island where a Pan American Airways hotel had been located) is situated in the center of the map above the black circle enclosing a “1.” The north-south dashed line depicts the International Date Line, with Wake being on the opposite (west) side of it; thus, Wake is a calendar day earlier than places to the east of it. Prior to Wake’s capture, the island’s U.S. Navy-Marine garrison had been an important intelligence-gathering center and warning outpost. Wake (actually Peale Island) had also been a stopover for Pan Am’s big China Clipper flying boats. To the east of Wake Island the Pacific outposts are in American hands. Japanese island strongholds lie to the west of Wake and much of the south; e.g., the Marianas, Guam, and the Marshall and Gilbert islands, which the Americans took during campaigns that lasted from November 1943 through August 1944. The Japanese remained in occupation of Wake Island, weathering periodic U.S. bombing and occasional raids, until September 4, 1945.

|  |

Left: Columns of billowing greasy black smoke rise from on either side of Wake Island’s airstrip after a Japanese air raid in December 1941. During the 16‑day siege of Wake Island, the Japanese lost 7 aircraft, 2 destroyers, 2 transports, 2 patrol boats, and over 1,100 men, with many more wounded. U.S. dead were 122 (including civilian contractors), with 49 wounded and 2 missing. Interned along with U.S. military prisoners were 1,104 civilians. Among the latter group, 180 unfortunates died in brutal captivity in Japan and occupied China. Wake’s heroic defense and sacrifice were the chief bright spots in the grim first months of the Pacific War.

![]()

Right: Just hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor, 36 Japanese medium bombers flown from bases on the nearby Marshall Islands attacked Wake Island, destroying 8 of the 12 F4F‑3 Wildcat fighter aircraft belonging to Marine Corps fighter squadron VMF‑211 on the ground. This photo, taken after the Japanese had captured the island, shows the wreckage of Wildcat 211‑F‑11, flown by executive officer Capt. Henry T. Elrod on the morning of December 11, 1941, in the attack that sank the destroyer Kisaragi with the loss of all 167 hands—the first Japanese warship sunk by a U.S. fighter pilot. “Hammerin’ Hank” Elrod was posthumously awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor—the first aviator to receive the medal in World War II—for his actions on Wake during the second Japanese landing attempt on December 23. Sadly by nightfall that day, the island’s defenders were left with no serviceable aircraft to turn back the invaders.

|  |

Left: Japanese Patrol Boat No. 32 and Patrol Boat No. 33 were 2 ex-destroyers reconfigured in 1941 to launch a landing craft carrying 250 naval infantrymen over a stern ramp. In the photo they have been run aground on the south coral shore of Wake Island near the airstrip before dawn on December 23, 1941. Island defenders, with a 3 in./76.2 mm gun, managed to draw a bead on beached Patrol Boat No. 33, less than 500 yards/457 m from their position. Some of their 15 projectiles touched off the ship’s magazine, and the warship began to burn. The illumination provided by the burning ship revealed her sister ship, Patrol Boat No. 32, which was hit with 5 in./127‑mm shells from coastal artillery guns. Twenty-five minutes later that boat too was completely demolished. The Japanese marines, however, were able to slip over the patrol boats’ sides in the darkness and sprint across the coral reef for cover.

![]()

Right: Hundreds of prisoners of the Japanese garrison, U.S. military, Pan Am, and civilian contractor personnel employed by a cooperative of 8 construction companies, are marched to the Nita Maru, a large transport ship waiting off Wake Island’s south shore on January 12, 1942. The men could not possibly know that their lives as POWs on Wake during the past 3 weeks had been relatively easy compared to the true hell that awaited them at their destination, POW camps in China. In October another 260 Wake captives wound up at a slave labor camp near Sasebo, Japan. By April 17, 1944, 53 of the original 260 were dead. Ninety-eight civilian contractors whom the Japanese had kept on Wake were brutally killed at the atoll’s shoreline the previous October.

Radio Broadcast Announcing Fall of Wake Island to Japanese

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click