U.S. TARGETS JAPAN FOR STARVATION

Tinian, Mariana Islands · March 27, 1945

An island nation, Japan was vulnerable to a blockade of essential food and strategic materials. On this date, March 27, 1945, the U.S. Army Air Forces and the U.S. Navy, hoping to put the final nail in the enemy’s coffin, kicked off Operation Starvation, the aerial mining of Japanese waters. Three nights later 85 more “miners” followed suit. By beginning the nighttime aerial dropping of mines (eventually 12,000 mines) in rivers and coastal waters, Maj. Gen. Curtis LeMay’s Marianas-based B‑29 Superfortresses accessed Japanese waters too shallow or close to land for Allied submarines to enforce a sea blockade.

The five-month-long aerial campaign saw the near destruction of Japanese coastal shipping and shipping lanes, halting Japan’s importation of critical raw materials and food and forcing the abandonment of 35 of 47 vital convoy routes. Adding LeMay’s incendiary raids on urban and military-industrial areas to the destructive mix reduced Japan’s overall production in 1945 by two-thirds compared with the year before. Already in 1940 rice—the chief item in the Japanese diet—had been subject to rationing due to bad harvests in the Japanese colony of Korea and the demands of the Japanese military in China (since 1937) and Southeast Asia (since 1941). Fish, the other dietary staple, had all but ceased to be distributed in some areas in 1944. Food supplies were so meager that the average Japanese citizen was living at or near starvation level. Average civilian caloric intake in 1945 was 78 percent of the minimum needed for health and physical performance.

By the end of June 1945 the civilian population began to show signs of panic. Experts predicted deaths by starvation would exceed seven million were Japan to somehow muster the will and resources to wage war through 1946. With the benefit of hindsight, Japan’s formal surrender on September 2, 1945, was inevitable even without the U.S. immolating Hiroshima and Nagasaki, without the Soviet Union’s entry into the war on August 8, 1945, and without the ghastly number of casualties projected by an Allied invasion of the Japanese island of Kyūshū in late 1945 and the main island of Honshū in April 1946 (Operation Downfall). But the horrors of the Pacific Islands campaign were so fixed in the minds of U.S. military and political leaders that the fire-and-sword strategy of using atomic weapons appeared to be the least costly way to bring World War II to an end.

![]()

Operation Starvation, March–August 1945

|  |

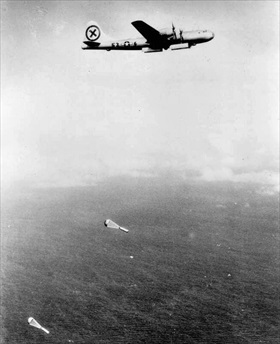

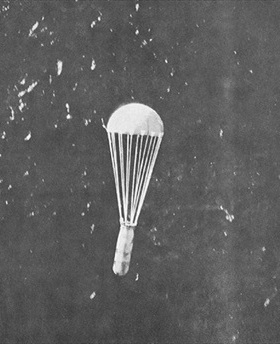

Left: Overseen by Maj. Gen. Curtis LeMay, Operation Starvation was a joint U.S. air and naval effort to strangle Japanese maritime traffic by the aerial mining of Japan’s harbors and straits. The main objectives of Operation Starvation were to prevent the importation of raw materials and food into Japan, prevent the supply and movement of military forces, and disrupt shipping in Japan’s Inland Sea, the body of water that separates Honshū, Shikoku, and Kyūshū islands. Beginning on March 27, 1945, B‑29 Superfortresses assigned to Operation Starvation dropped 825 parachute-retarded influence mines with magnetic and acoustic exploders. The initial sortie was followed up on March 30 by 1,528 more. Some models of mines had water-pressure-displacement exploders. Aerial mining proved the most efficient means of destroying Japanese shipping during the war. In terms of damage per unit of cost, it surpassed the strategic bombing and the U.S. submarine campaigns against Japan.

![]()

Right: A 1,000 lb/454 kg Mk 26 sea mine being dropped by a B‑29, 1945. LeMay’s XXI Bomber Command (a unit of the Twentieth Air Force in the Mariana Islands) laid 12,135 mines in 26 fields on 46 separate missions. The Japanese employed 349 vessels and 20,000 men to clear mines. Over the course of the war, aerial, surface, and submarine mine-laying sank or damaged over 2 million tons of enemy shipping, a volume representing nearly one quarter of the prewar strength of the Japanese merchant marine. After the war, the commander of Japan’s mine-sweeping operations noted that he thought the U.S. mining campaign could have led directly to the defeat of Japan on its own had it begun earlier.

|  |

Left: Sea mines prepared by mine assembly personnel on Tinian Island in the Northern Marianas are ready for loading onto B‑29.

![]()

Right: A 2,000 lb/907 kg MK 25 mine is loaded into a B‑29’s bomb bay. Aircraft were loaded with an average of 12,000 lb/5,443 kg of mines consisting of a mixture of 2,000 lb/907 kg MK 25 mines and 1,000 lb/454 kg MK 36 mines. A mix of magnetic and acoustic actuating devices was used with various sensitivity settings, a random mix of arming delays between 1 and 30 days, and ship counts between 1 and 9.

Operation Starvation: The 1945 Aerial Mining Campaign to Destroy Japanese Shipping and Bring Japan to Its Knees (Skip the first 8 minutes)

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click