U.S. SUPREME COURT OKAYS JAPANESE AMERICAN INTERNMENT

Washington, D.C. • December 18, 1944

On December 7 and 8, 1941, the Empire of Japan launched an unprovoked air and sea attack on U.S. military assets in the Central and Western Pacific Ocean, at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and the Philippines, respectively. On December 11, 1941, the U.S. Congress declared war on the aggressor nation. Seventy days later, on February 19, 1942, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. The order authorized the Secretary of War and the U.S. armed forces to remove people of Japanese ancestry from what became known as Military Exclusion Areas 1 and 2. Violation of mandates issued under Executive Order 9066 by top War Department personnel were henceforth federal crimes. The military exclusion areas were legally off limits to Japanese-born U.S. residents (labeled “alien enemies”) and Japanese American citizens who were born in the U.S. (labeled “non-alien enemies”). FDR’s order contradicted many years’ worth of Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and U.S. naval intelligence data that attested to residents of Japanese descent posing no national security threat, and the order flew in the face of government studies that recommended against mass exclusion and incarceration.

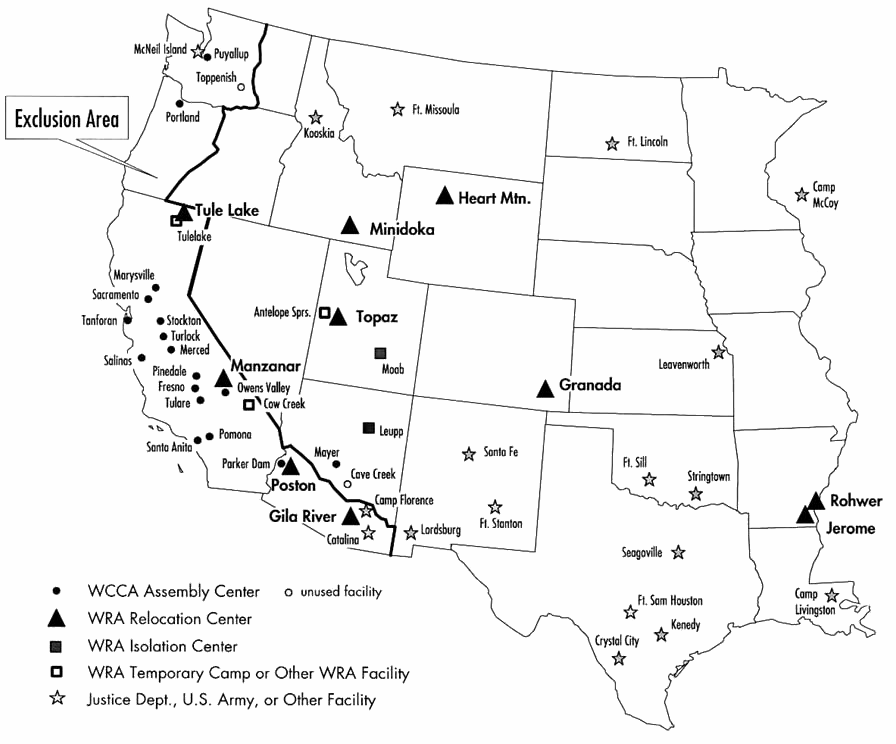

Executive Order 9066 set in motion the forced mass exodus and relocation of more than 126,000 people of Japanese ancestry to sites where they were confined indefinitely, surrounded by barbed wire fencing and armed guard towers. Most people uprooted, dispossessed of their real property (homes, businesses, farms, farming implements, cars and trucks, fishing boats, bank and savings accounts, etc.), and incarcerated in the boondocks came from the West Coast and two-thirds of them (nearly 80,000) were American citizens. Almost half were children. In accordance with Roosevelt’s executive order, the military transported the “evacuees” to 27 sites in states west of the Mississippi River (see map below).

Japanese nationals and American-born West Coast residents swept up by FDR’s Civilian Exclusion Order (official name of the military evacuation order) put their lives on hold, perhaps consoled by the Japanese expression “shikata ga nai,” or “it can’t be helped.” Owner of a flower nursery in San Leandro, California, Kakusaburo Korematsu, his wife, and all but one son obeyed their evacuation order upon receipt. Twenty-three-year-old Fred did not. In what was the most momentous decision of his life, Fred opted to disobey the curfew and exclusion orders. He thought that the statute under which he faced removal and imprisonment was a violation of his civil rights as an American.

Fred Korematsu went into hiding only to be arrested on May 30, 1942. Eventually he landed in the San Francisco county jail. At the behest of the American Civil Liberties Union Korematsu agreed to use his arrest to test the legality of Japanese American eviction and incarceration. His attorneys charged the president, Congress, and the military with having engaged in unconstitutional actions against Korematsu and, in effect, Japanese Americans by seeking to deny them a hearing or other due process protections. On September 8, 1942, Korematsu was convicted in a U.S. district court for violating military exclusion orders issued under the authority of Executive Order 9066. In time he ended up in the Topaz Relocation Center in Utah where his parents had been sent.

Twice Korematsu appealed his 1942 conviction without success. In October 1944 the nation’s highest court agreed to hear his appeal. On this date, December 18, 1944, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in a 6‑to‑3 decision that the evacuation order violated by Korematus was valid, one justice opining that the “martial necessity arising from the danger of espionage and sabotage” by Japanese Americans and Japanese nationals warranted the evacuation order. The majority of justices dodged the constitutional racial discrimination issue in the case. Two dissenting justices faced that issue head on: one said the nation’s wartime security concerns were not sufficient to strip Korematsu and over 126,000 people of Japanese descent of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. A second dissenter denounced the decision as the “legalization of racism.”

Executive Order 9066 Cleared the Way for the Forced Exile and Relocation of West Coast Japanese Nationals and Japanese Americans

|

Above: Map showing (a) the massive West Coast World War II exclusion area (Military Areas 1 and 2) and (b) confinement sites in the continental U.S. for Japanese Americans as well as for over 31,000 suspected enemy aliens and their families interned under the Enemy Alien Control Program. The 10 hastily built incarceration camps, euphemistically called “relocation centers,” are identified by black triangles. The camps were built in 7 states all west of the Mississippi. All the camps were remote; many were situated in desolate deserts or swamplands. U.S. Department of Justice-administered camps (there were 27) and U.S. Army camps (18) are represented by stars; for example, Fort Missoula Internment Camp in Montana and Fort Lincoln Internment Camp 5 miles/8 km south of Bismarck, North Dakota. It was to these often former Civilian Conservation Corps camps that people arrested in December 1941 and early 1942—that is, before Executive Order 9066 was in place—as well as thousands of German and Italian nationals living in the U.S. or deported from Central and South America were brought. In the map legend, WCCA = Wartime Civil Control Administration, WRA = War Relocation Authority. Purportedly for their own safety roughly 75,000 U.S. Japanese American citizens and 45,000 immigrants from Japan living in the U.S., a number equivalent to the population of Wilmington, N.C., would eventually be torn from their homes, neighborhoods, farms, fishing boats, and places of employment and worship in California (where the majority lived), Western Oregon and Washington, and Southern Arizona as part of the single-largest forced relocation in U.S. history. Eighty-five percent of all ethnic Japanese living in the continental U.S. were affected. On December 17, 1944, just a month after the notorious decision by the U.S. Supreme Court that upheld the legality of Executive Order 9066, the Roosevelt administration rescinded the military exclusion order, ending mass forced relocation and allowing internees to return to the West Coast. Except for Tule Lake, the WRA camps would be emptied by the end of 1945.

|  |

Left: Overseen by U.S. soldiers, these Japanese American “evacuees” await their fate: either a train ride to an assembly center for initial processing while their relocation center was under construction or a train ride to their finished abodes. Fred Korematu’s assembly center was the Tanforan Racetrack south of San Francisco, where over a month earlier his parents and siblings had been summoned by their military evacuation order. People incarcerated at Tanforan lodged in cramped, crowded, and dirty horse stalls infested with mice and other vermin. Full-term women gave birth in such stalls.

![]()

Right: This bleak 1942 aerial view depicts the Topaz Relocation Center at Topaz, Utah. Complete with armed guards, watch towers, and barbed wire, the camp became the temporary home “for the duration of the war” for 9,000 Japanese Americans, among them Fred Korematsu and his family who were forcibly evicted from the U.S. West Coast. The poorly built wooden barracks typically consisted of 4 rooms (“apartments”) each (1 room per family) and were occupied in roughly 14 weeks from start to finish. Each drab, thin-walled apartment was furnished with hard army cots, a potbellied stove to heat the space, and 1 naked light bulb screwed into a ceramic socket on the end of a long cord hanging from a rafter. There were no ceilings. The Topaz camp was closed in October 1945.

|  |

Left: Acclaimed civil rights activist and pioneer Fred Korematsu (1919–2005), who fought against World War II Japanese internment, described by many Americans as the worst official civil rights violation in modern U.S. history. Nineteen-year-old Korematsu, Castlemont High School photograph, Oakland, California, 1938. When the U.S. Army forced Japanese Americans into confinement camps during World War II, Korematsu refused to comply with the orders and was arrested, tried, and convicted in federal court. Korematsu fought his conviction and confinement, his case reaching the U.S. Supreme Court in 1944.

![]()

Right: In recognition of his courageous stand against the injustice of wartime detention and confinement, President Bill Clinton in 1998 awarded Fred Korematsu the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian award given on behalf of the U.S. government. Four decades after Korematsu’s 1942 conviction, the original federal court reopened his case. The government’s own records proved that the wartime government had suppressed, altered, and destroyed material evidence when it was arguing the Korematsu case before the Supreme Court. The writ of error coram nobis litigation cleared Korematsu’s name as well as the names of all other people incarcerated under Executive Order 9066. It also laid the legal cornerstone for the 1988 Civil Liberties Act signed by President Ronald Reagan, which formally acknowledged that the wartime exclusion and detention of Japanese Americans had been unreasonable. (A late 20th-century study concluded that the internal government decisions that led to Roosevelt issuing Executive Order 9066 were based on racial prejudice, wartime hysteria, and failed political leadership.) The Civil Liberties Act granted $20,000 in reparations to each survivor of the camps (a little over 82,000 people), costing the U.S. Treasury $1.6 billion (equivalent to over $4.38 billion today).

The Fred Korematsu Story

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click