U.S. SUCCESSFULLY DETONATES WORLD’S FIRST ATOMIC BOMB

Trinity Test Site near Alamogordo, New Mexico • July 16, 1945

On this date in 1945 the first detonation of an atomic bomb directly led to greater unimaginable destruction when “Little Boy” and “Fat Man” immolated Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9, 1945, respectively. Up until July 16, 1945, military brass and military and civilian scientists could only speculate about the massive explosive power of this new type of bomb. The majority of scientists involved in the Manhattan Project, the $2 billion U.S. Army’s top-secret nuclear nuclear weapons program, never wanted to build an atomic bomb nor did they want it to be used against civilians. Their reservations were given a cold shoulder, most famously in the case of Hungarian-born physicist Leó Szilárd’s petition that was intended for U.S. President Harry S. Truman and high-ranking officials and that was eventually co-signed by over 50 Manhattan Project personnel. Szilard’s co-author from a half-dozen years earlier, the German-born theoretical physicist Albert Einstein, in a petition the 2 men delivered to the White House that sparked the creation of the Manhattan Project, was barred from working directly for, or consulting on, the Manhattan Project owing to the renown scientist’s left-leaning politics and peace activism. Despite having nothing to do with the project he inseminated, Einstein was quoted as saying “Woe is me” upon learning of Hiroshima’s fate.

Both Little Boy and Fat Man had an interesting gestation period. The engineering design phase was fraught with danger. Little Boy was a relatively straightforward gun-type fission weapon while Fat Man was a complex implosion-type nuclear weapon. Little Boy used highly enriched uranium‑235, which is fissile (capable of being split or divided), meaning it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction leading to an explosive energy release. Fat Man used plutonium‑239 to achieve an explosive energy release. A gun-type fission weapon earlier than Little Boy was Thin Man, which like Fat Man used plutonium as its fissile material. Further development of Thin Man stopped when the spontaneous fission rate of plutonium was discovered too high for use in a gun-type design; i.e., the device would undergo a preliminary chain reaction that destroys the fissile material before it is ready to produce a large explosion.

The gun-type fission weapon of Thin Man found its way into Little Boy when uranium instead of plutonium was the weapon’s fissile material. Fat Boy continued as before as an implosion-type nuclear weapon with plutonium as its fissile material. Implosion was tricky. The weapon designers created 32 polygonal lenses that focused the implosion into a spherical shape resembling a soccer ball. Exploding-bridgewire detonators, invented at the Manhattan Project’s Los Alamos Laboratory, got the detonation just right.

The complexity of an implosion-design plutonium bomb called for a full-scale test. J. Robert Oppenheimer, director of the Los Alamos Laboratory that designed the 2 types of nuclear bombs, codenamed the isolated test site “Trinity.” The test device, or “Gadget,” was of the same design as Fat Man. The weekend Trinity Test attracted some 425 people. When the bomb exploded it released the explosive energy of 25 kilotons of TNT ± 2 kilotons in addition to a huge cloud of radioactive fallout. Norris Bradbury, Trinity Test bomb assembly group leader, remarked that the explosion “did not fit any preconceptions possessed by anybody.” Richard Feynman, American theoretical physicist and Nobel Prize laureate, was stationed 20 miles/32 kilometers from the detonation point, observed: “A big ball of orange, the center that was so bright, becomes a ball of orange that starts to rise and billow a little bit and get a little black around the edges, and then you see it’s a big ball of smoke with flashes on the inside of the fire going out.” Another witness that day said he “could feel the heat on my face a full 20 miles/32 kilometers away.” Trinity Test director Kenneth Bainbridge called the detonation a “foul and awesome display.”

Trinity Test Site, New Mexico, 1945: Detonating World’s First Nuclear Bomb

|  |

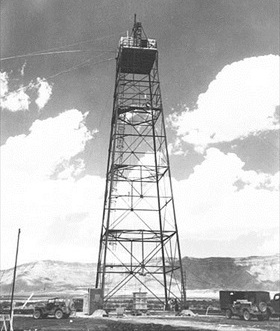

Left: The 100 foot-/30 meter-tall steel tower constructed at a small Army airfield for the Trinity test. The name Trinity was inspired by the “three-person’d God” in a sonnet written by English poet and cleric John Donne. The test site was located on the Alamogordo Bombing and Gunnery Range (now part of the White Sands Missile Range) in a particularly dry stretch of southern New Mexico desert called the Jornada del Muerto—Spanish for “Journey of the Dead Man.” Trinity lay 200 miles/322 kilometers south of Los Alamos, where the atomic bombs were designed and built.

![]()

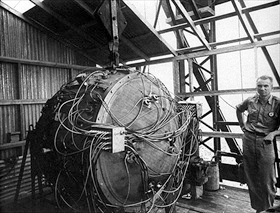

Right: The explosives of 5-ton Gadget were carefully hoisted to the corrugated-steel shelter at the top of the tower for final assembly in mid‑July 1945.

|  |

Left: Norris Bradbury, bomb assembly group leader, stands next to the partially assembled Gadget atop the test tower, July 15, 1945. Among other things, Bradbury had to ensure that the series of detonators needed to set off a nuclear chain reaction inside Gadget fired simultaneously within a fraction of a millionth of a second, otherwise the plutonium would “fizzle” and not produce a nuclear explosion. The July test of the plutonium device turned out to be an unqualified success. Frank Oppenheimer watched his brother Robert hardly breathing in the last few seconds before Gadget exploded; after it did his brother’s face relaxed into an expression of tremendous relief. In something of an understatement Robert Oppenheimer simply said: “I guess it worked.” Oppenheimer is often called the “father of the atomic bomb.”

![]()

Right: Trinity was a test of an implosion-design plutonium device, the same conceptual design used in the second nuclear device dropped on Japan—Fat Man—which was detonated over Nagasaki, Japan, on August 9, 1945. This photo was taken at 5:30 a.m., a 0.016 second after test detonation. The searing light of the explosion was more intense than anything ever witnessed before and could have been seen from space. Its core temperature was 4 times greater than that at the sun’s core. The awesome roar of the air blast 30 seconds later “warned of doomsday,” reported one witness. Oppenheimer later remarked that the detonation reminded him of a passage from the second-century BCE Hindu Bhagavad Gita: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”

|  |

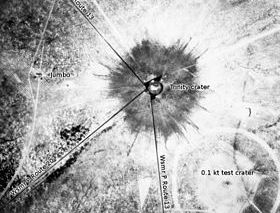

Left: An aerial photograph of the Trinity crater shortly after the test. The bomb blast left a crater of radioactive glass 10 foot/3 meter deep and 1,100 foot/335 meter wide. Nothing remained of the steel tower. The shock wave was felt over 100 miles/161 kilometers away, and the mushroom cloud reached 7.5 miles/12 kilometers in height. President Harry S. Truman was positively giddy with new confidence on a swift victory in the 4‑year Pacific War. From the Big Three victors’ conference in Potsdam near the former Nazi capital, Berlin, Truman wrote his wife in mid-July 1945: “We’ll end the war a year sooner now, and think of the kids [U.S. service members—ed.] who won’t be killed.”

![]()

Right: J. Robert Oppenheimer (center, in dark suit and light-colored hat), Brig. Gen. Leslie Groves (military head of the Manhattan Project in khaki uniform to Oppenheimer’s left), and other scientists and military personnel inspect the melted remains of the test tower at ground zero after the Trinity blast. The photo was taken in September when some participants returned with news reporters. Note the men wearing shoe covers to keep from picking up radiation. The test site was littered with lopsided marbles and knobbly sheets that later became known as Trinitite. Trinitite was primarily quartz and feldspar, tinted sea green with minerals in the desert sand, with droplets of condensed plutonium sealed into it.

University of California Television: The Manhattan Project

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click