U.S. SEVERS COAL LINK TO JAPAN INDUSTRY

Aboard the U.S. Carrier Shangri-La • July 14, 1945

On this date and the next in 1945, less than four months after the start of the joint U.S. air and naval effort to strangle Japanese maritime traffic by the aerial mining of Japan’s harbors and straits, aptly named Operation Starvation, Navy air groups destroyed over half the train ferries between the northern Japanese island of Hokkaido and the main island of Honshū. The largest, most populated of the Home Islands, Honshū was the center of Japan’s industry and the site of most of the country’s rail lines. Almost overnight the amount of Hokkaido coal delivered to Honshū factories dropped more than 80 percent, seriously crippling Japanese industry.

Literally between a rock and a hard place, Japan saw its imports of selected commodities, including coal and foodstuffs, which totaled over 20 million tons in 1941, cut in half in 1944 and plummet to 2.7 million tons in June 1945. Japanese censors blocked delivery of letters to service members overseas on account of civilians complaining bitterly about the lack of food, water, petroleum products, and just about everything else back home. Vice Admiral Paul Wenneker, German naval attaché in Tokyo (1940–1945), believed it was submarine warfare that brought island inhabitants to their knees. Wenneker had personal knowledge of the U.S. submarine blockade of Japan, for he was in charge of the blockade-running naval operation that brought German goods such as opticals, machine tool equipment, special service personnel, and plans for airplanes to Japan in return for vital Asian materials like quinine and tin. “But this was not so easy an arrangement because of the American submarines on the route between Japan and the south,” by which he meant Penang or Singapore on the Malay Peninsula. “It was terrible,” he told his American interrogator. “Sometimes the entire convoy including all my material would be lost. It seemed that nothing could get through.”

Yes, the U.S. submarine blockade had been responsible for the drop in imports through the early part of 1945; however, it was the B‑29 air-dropped mines of Operation Starvation, overseen by Maj. Gen. Curtis LeMay, that provided the tipping point. By August 1945, the month in which LeMay’s 509th Composite Group, part of the U.S. Twentieth Air Force, vaporized Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the country had less than half the food and raw materials needed to continue the fight. Reports surfaced of hungry civilians reduced to eating sawdust while Japan’s fleet of warships rusted at anchor due to lack of fuel, and while Tokyo’s military rulers dithered over accepting the Allies’ demand for unconditional surrender as expressed in the Potsdam Declaration of July 26, 1945.

After the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki Japan’s Emperor Hirohito (posthumously referred to as Emperor Shōwa) personally had no fight left, which made all the difference. In a royal understatement, Hirohito told his subjects in a radio broadcast on August 15: “Despite the best that has been done by everyone . . . the war situation has developed not necessarily to Japan’s advantage.” To continue the fight would “result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation.”

![]()

Grabbing Japan’s Attention: Operation Starvation

|  |

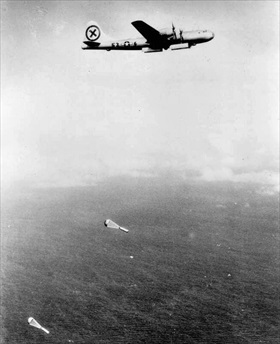

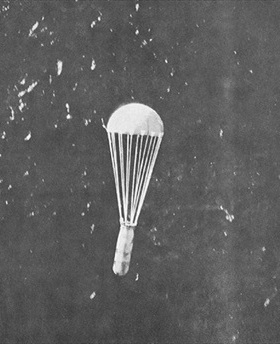

Left: Beginning on March 27, 1945, four-engine B‑29 Superfortresses assigned to Operation Starvation dropped 1,000 parachute-retarded influence mines with magnetic and acoustic exploders. The initial sortie of heavy bombers was followed up by 1,528 more. Some models of mines had water-pressure-displacement exploders. Aerial mining proved the most efficient means of destroying Japanese shipping during the war. In terms of damage per unit of cost, it surpassed the strategic bombing and the U.S. submarine campaigns.

![]()

Right: A 1,000 lb M26 sea mine being dropped by a B‑29, 1945. The Twentieth Air Force laid 12,135 mines in 26 fields on 46 separate missions. Eventually most of the major ports and straits of Japan were repeatedly mined, severely disrupting Japanese logistics and troop movements for the remainder of the war. The mines sank or damaged 670 ships totaling more than 1,250,000 tons.

|  |

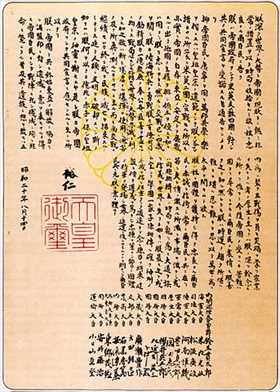

Left: Imperial rescript from Emperor Hirohito ordering Japan’s capitulation and the end to World War II. It was written by the Japanese government on August 14, 1945, in response to the Allies’ Potsdam Declaration of July 26, 1945, sanctioned by the emperor, signed by the cabinet, and recorded by Hirohito on a phonograph record. Then at noon on August 15 the rescript was broadcast to the nation. In his Gyokuon-hōsō (lit. “Jewel Voice Broadcast”), Hirohito admonished his subjects to “endure the unendurable and bear the unbearable.” Click the audio bar to hear Hirohito read the Imperial Rescript on the Termination of the War.

![]()

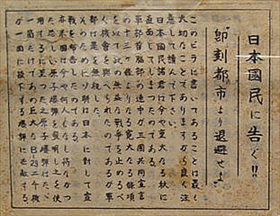

Right: A leaflet dropped from a B-29 on Japan after the bombing of Hiroshima. Translation: Notice to the Japanese People! Evacuate the city immediately. What this leaflet contains is extremely important, so please read carefully. The Japanese people are facing an extremely important autumn. Your military leaders were presented with thirteen articles for surrender by our three-country alliance to put an end to this unprofitable war. [The reference here was to the Potsdam Declaration issued by the U.S., Great Britain, and Nationalist China on July 26, 1945.] This proposal was ignored by your army leaders. Because of this the Soviet Republic intervened. In addition, the United States has developed an atom bomb, which had not been done by any nation before. It has been determined to employ this frightening bomb. One atom bomb has the destructive power of 2000 B‑29s. This frightening fact should be understood by you by observing what kind of situation was caused when only one was dropped on Hiroshima.

1945 U.S. Army Air Forces Strategic Bombing of Japan

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click