U.S. MINES INDOCHINA WATERS

Honolulu, Hawaii · October 29, 1943

In World War II’s Pacific Theater, sea mines—explosive underwater devices that damaged, sank, or deterred Japanese warships, submarines, and maritime commerce—were weapons that had difficulty gaining the same respect as guns, bombs, and torpedoes enjoyed in the U.S. arsenal. Over time, however, a small number of mining advocates in both the U.S. Navy and the U.S. Army Air Forces influenced their service bosses enough to ensure the growth of offensive mine-laying, equipment development, and combat experience. On this date in 1943 U.S. submarines began mining the waters off French Indochina. The following March the U.S. Navy mounted a direct aerial mining attack on Japanese shipping on Palau Island in the western Pacific, which stopped 32 Japanese ships from escaping Palau’s harbor. Combined with bombing and strafing attacks, the operation sank or damaged 36 ships. The most successful mining operations were those conducted by the Allied air forces laying aerial minefields. Beginning with a very successful attack on the Yangon River in Burma (Myanmar) in February 1943, B‑24 Liberators, PBY Catalinas, and other available bomber aircraft took part in localized mining operations in the China Burma India (CBI) Theater and in the Southwest Pacific (Philippines, the Dutch East Indies, Borneo, New Guinea, and the western Solomon Islands). British and Royal Australian air forces carried out 60 percent of the sorties and the U.S. Army Air Forces and U.S. Navy carried out the balance. U.S. Adm. Thomas C. Kinkaid, who directed nearly all RAAF mining operations in the CBI, wrote in July 1944 that “aerial mining operations were of the order of 100 times as destructive to the enemy as an equal number of bombing missions against land targets.” The U.S. mining effort against the Japanese home islands proved very successful, closing major ports like Hiroshima on western Honshū, the largest home island, for days. At best, the Japanese succeeded in sweeping only about 50 percent of American acoustic mines (they measured sound of certain frequencies). Pressure mines, the most commonly used against Japan near the end of the war, were even more difficult to sweep. By war’s end, more than 25,000 U.S.-laid sea mines were still in place. Over the next 30 years, more than 500 minesweepers were damaged or sunk in continuing clearance efforts.

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”ASINList” width=”600″ height=”200″ title=”Recommended Reading” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”False” show_border=”False” asin=”0275984192,0307275361,1249327822,0141001461,1596987693,0688016200,0760339759,0812968581,0143123017,0757001629″ /]

Operation Starvation: Strangling Japanese Maritime Traffic

|  |

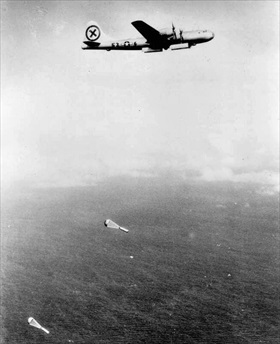

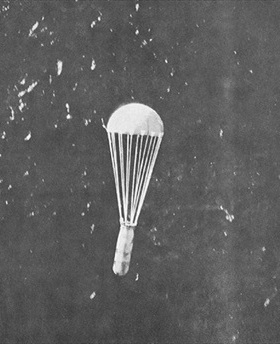

Left: Overseen by Maj. Gen. Curtis LeMay, Operation Starvation was a joint U.S. air and naval effort to strangle Japanese maritime traffic by the aerial mining of Japan’s harbors and straits. The main objectives of Operation Starvation were to prevent the importation of raw materials and food into Japan, prevent the supply and movement of military forces, and disrupt shipping in the Inland Sea. Beginning on March 27, 1945, B-29 Superfortresses assigned to Operation Starvation dropped 825 parachute-retarded influence mines with magnetic and acoustic exploders. The initial sortie was followed up on March 30 by 1,528 more. Some models of mines had water-pressure-displacement exploders. Aerial mining proved the most efficient means of destroying Japanese shipping during the war. In terms of damage per unit of cost, it surpassed the strategic bombing and the U.S. submarine campaigns against Japan.

![]()

Right: A 1,000 lb Mk 26 sea mine being dropped by a B‑29, 1945. LeMay’s XXI Bomber Command (a unit of the Twentieth Air Force in the Mariana Islands) laid 12,135 mines in 26 fields on 46 separate missions. The Japanese employed 349 vessels and 20,000 men to clear mines. Over the course of the war, aerial, surface, and submarine mine-laying sank or damaged over 2 million tons of enemy shipping, a volume representing nearly one quarter of the prewar strength of the Japanese merchant marine. After the war, the commander of Japan’s mine-sweeping operations noted that he thought the U.S. mining campaign could have led directly to the defeat of Japan on its own had it begun earlier.

|  |

Left: Sea mines prepared by mine assembly personnel on Tinian Island in the Northern Marianas are ready for loading onto B‑29s.

![]()

Right: A 2000 lb MK 25 mine is loaded into a B‑29’s bomb bay. Aircraft were loaded with an average of 12,000 lb of mines consisting of a mixture of 2,000 lb MK 25 mines and 1,000 lb MK 26 mines. A mix of magnetic and acoustic actuating devices were used with various sensitivity settings, a random mix of arming delays between 1 and 30 days, and ship counts between 1 and 9.

1945 U.S. Army Air Forces Strategic Bombing of Japan

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click