U.S. MARINES STORM ASHORE AT CAPE GLOUCESTER

West New Britain, Papua New Guinea • December 26, 1943

Following the successful conclusion of the U.S. and Australian Buna-Gona Campaign on New Guinea’s southeastern peninsula in late-January 1943, the Allies moved west along the island’s north shore. Gen. Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in the Southwest Pacific Area, used Buna (see map, lower center) as the staging base for attacks up the north coast after the exhausted and battle-depleted Allied troops had recovered and were reconstituted. During these 6 months of recovery, as each side reinforced and replaced earlier losses on New Guinea, the Japanese still retained the strategic initiative on the island, and they still held the preponderant air, naval, and ground strength in the Southwest Pacific, despite being forced to abandon their Solomon Islands forward base on Guadalcanal in February 1943.

The stalemate in the Southwest Pacific was broken at the beginning of September 1943 by a joint operation launched by MacArthur and U.S. Rear Admiral Daniel E. Barbey, who headed up what eventually became the VII Amphibious Force—the ships that carried the ground forces, their equipment, and supplies. The first coordinated airborne and amphibious assault in the Pacific occurred at Lae in the Huon Gulf (center in map). Finschhafen northwest of Lae, a Japanese strongpoint that guarded the western side of the 60‑mile/96‑km-wide Vitiaz and Dampier Straits separating New Guinea and New Britain, proved a tougher nut to crack. In the meantime, MacArthur’s choice to lead his new Alamo Force, the U.S. Sixth Army’s Lt. Gen. Walter Krueger, was training his growing number of divisions to fight as amphibious task forces just as the U.S. was gaining overwhelming numerical superiority in air and naval strength in the Southwest and South Pacific areas. The U.S. also now held the strategic and tactical initiative and could select the dates and locations for forthcoming operations that would most advance the Allied cause.

In December 1943 MacArthur ordered amphibious assaults across the Vitiaz and Dampier Straits. In the predawn hours of December 15 the U.S. Army’s 112th Cavalry Regimental Combat Team, with help from a U.S. Marine amphibious tractor battalion and Allied naval and air units, seized Arawe, a Japanese air and PT (patrol torpedo boat) base on the southwestern coast of New Britain garrisoned by 120 soldiers and sailors. And on this date, December 26, 1943, the 1st Marine Division, veterans of the Guadalcanal Campaign (August 7, 1942, to February 9, 1943), landed at full strength at Cape Gloucester on the island’s northwestern tip.

Aided by naval salvos from American and Australian warships and by aerial attacks and smoke screens from the 2 nations’ air forces, the 1st Marine Division’s landing at Cape Gloucester proved successful. Four days later, against only light enemy opposition, the Marines secured the airfields that were the initial objective of the operation. Heavy fighting tapered off after the first 2 weeks of 1944. Towards the end of February the Japanese began to leave their defensive positions for the relative safety of Rabaul on the opposite end of the island. When U.S. reinforcements arrived on New Britain, the 112th Cavalry Regiment deployed to New Guinea in early June. The 1st Marine Division returned to the Solomons, to the Russell Islands 30 miles/48 km northwest of their Guadalcanal stomping grounds, for rest and refitting before being dispatched to Peleliu in mid-September 1944. American casualties (killed and wounded) during the Arawe and Cape Gloucester operations, which ended April 22, 1944, numbered 1,863, with 4 missing. Japanese dead amounted to just over 1,300, with an unknown number of wounded and missing.

![]()

Battle of Cape Gloucester, December 26, 1943, to April 22, 1944

|

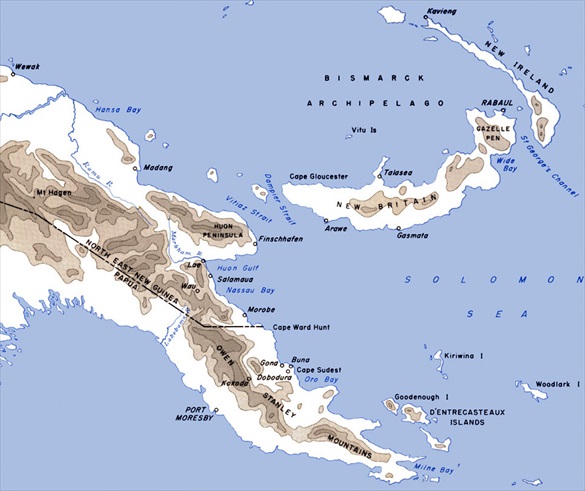

Above: Map of Eastern New Guinea and Japanese-occupied New Britain. The Japanese bastion of Rabaul appears in capital letters on the northeastern tip of the Taiwan-size island of New Britain and Cape Gloucester on the northwestern tip of New Britain. Arawe appears on the southwestern coast. The U.S. Army’s official history concluded that, in retrospect, the New Britain landings at Arawe (Operation Director) and Cape Gloucester (Operation Backhander) were not essential to the reduction of Rabaul as intended. (Actually Rabaul, with its estimated 100,000-plus ground troops, was neutralized for the remainder of the war by the Allies’ prolonged aerial attacks and by the “island hopping” strategy adopted in late 1943 to isolate and bypass enemy strongpoints, letting them literally “wither on the vine” as U.S. forces advanced.) The landings and occupation of Western New Britain simply seem to have tied down good men who could have been engaged to greater advantage elsewhere.

|  |

Left: Men and cargo of the 1st Marine Division, veterans of the campaign on Guadalcanal, are pictured aboard a landing craft for the invasion of Cape Gloucester, December 26, 1943. Despite the narrow beaches and the rough surf that buffeted their landing craft, 13,000 Marines and an excess of 7,500 tons of supplies came ashore in a single day.

![]()

Right: The initial landings in the Cape Gloucester area had as their ultimate objective the isolation of the huge Japanese air and naval base at Rabaul, 300 miles/483 km to the east on the other side of the island. The plan called for the Allies to secure Cape Gloucester’s beachheads and capture the dual airfields at Tuluvu to assist in the planned attacks on Rabaul. The Marines took the airfields on December 30, 1943, after slogging for 3 days through neck-deep swamps (marked “Damp Flats” on their maps), where men were actually killed by sodden branches falling from rotting trees. Impeded by heavy rains, Army aviation engineers worked around the clock to make Airfield No. 2, the larger of the Tuluvu airstrips, operational, a task that took them until the end of January 1944. In the end the 2 airstrips proved of marginal value to the Allies.

|  |

Above: Embattled Marines at times could see no more than a few feet ahead of them owing to the thick jungle (left frame). Retreating at first into the jungle of Cape Gloucester, Japanese soldiers finally gathered strength and counterattacked their Marine pursuers. The photo in the right frame shows Marines in the forest’s darkness fending off a Japanese attack using an M1917 Browning machine gun. Marines needed 3 weeks of hand-to-hand combat to clear more than 10,000 enemy troops from the immediate area around Cape Gloucester. The Cape Gloucester base effectively bottled up the 135,000 Japanese defenders at Rabaul, because the dense, jungle-swathed mountain ridges of the interior were impassable.

|  |

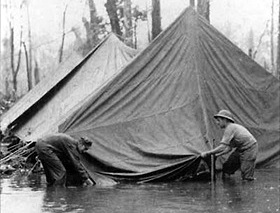

Left: Atrocious weather in the “green inferno” of New Britain proved to be the main problem for Marines and soldiers at Cape Gloucester. Monsoon deluges—as much as 16 inches of rain fell in a day—flooded foxholes and made life miserable in the base camp. Wet uniforms never really dried, and the men suffered continually from fungus infections, the so-called jungle rot, which readily developed into open sores. Mosquito-borne malaria threatened the health of the men, who also had to contend with other insects—“little black ants, little red ants, big red ants” on an island where “even the caterpillars bite.”

![]()

Right: Movement on foot or by vehicle through the island’s swamp, jungles, and tall, coarse kunai grass verged on the impossible, especially where monsoon rains had flooded the land or turned the volcanic soil into slippery mud.

“Rings Around Rabaul.” Victory at Sea Episode Makes Excellent Use of Japanese and American Footage

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click