U.S. LAUNCHES NEW GEORGIA CAMPAIGN IN SOUTH PACIFIC

New Georgia Islands, Solomon Islands • June 21, 1943

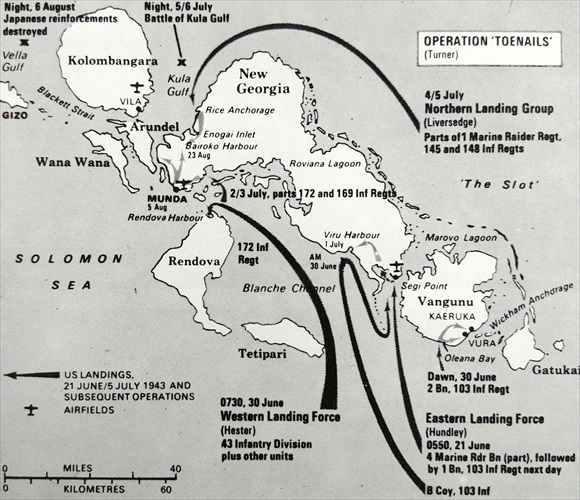

On this date in 1943, the U.S. kicked off Operation Toenails, as the New Georgia campaign was called, with unopposed landings by the elite 4th Marine Raider Battalion followed the next day by the Army’s 43rd Infantry Division. The year before, in October, the Japanese had reconnoitered New Georgia, 1 of 6 major islands and many smaller ones, in the 500‑mile/800‑kilometer-long Solomon chain, with the intent of building suitable airfields to support their combat action 150 miles/241 kilometers to the south on Guadalcanal, in the southeastern reaches of the Solomon Islands chain. Within weeks the Japanese Navy was operating out of airfields and bases at Munda Point on New Georgia’s northwestern tip and Vila on nearby Kolombangara Island, both at the approximate center of the Solomons (see map below). Starting on December 2, 1942, the 2 airfields incurred the wrath of massive and constant U.S. air strikes (medium and heavy bombers and fighters) and later naval shelling.

Having successfully evacuated the last members of their Guadalcanal garrison in early February 1943 after 6 months of horrific ground, air, and naval combat, the Japanese were determined to reinforce their defenses on the New Georgia group of islands. Despite the Guadalcanal setback, the Solomons remained a crucial part of Japan’s southern defensive perimeter because the islands were obvious stepping stones northward to the Japanese homeland. Thus in February and May 1943, the Japanese reinforced New Georgia Island with more equipment, soldiers (many were Guadalcanal veterans), and marines, making a total of 10,500 defenders and setting the scene for one of the most grueling battles of the Pacific War.

Just over a week after U.S. Marines and soldiers had stormed ashore on the south shore of New Georgia, American forces landed on nearby Rendova Island, which was secured on July 4, 1943. Rendova sat across a watery expanse from the Munda airfield. Amphibious landings were made elsewhere on New Georgia and on smaller islands, bringing troop strength to 32,000 men, but the main focus was on neutralizing the Munda airfield, defended by 200 Japanese. On August 5 American forces moved unopposed into Munda, which had been evacuated 2 days earlier by the enemy. But the conquest of Munda did not come easily. Some 1,200 reinforcements from the Japanese stronghold of Rabaul on New Britain rode down The Slot on the “Tokyo Express.” In a series of land and naval operations between early July and August 4, 1943, Japanese forces stymied and bloodied American units approaching from the north and east of the airfield. On July 17, in their last offensive against American lines, Japanese infantry unsuccessfully attacked U.S. beachheads but overran the 43rd Infantry Division’s command post. On August 3 the once-tenacious enemy—now exhausted, disease-ridden, reduced in numbers and firepower, and having lost communications with Rabaul headquarters—vacated the Munda area. Ten days later, after Navy Seebees had repaired the badly damaged airstrip, the first U.S. aircraft landed at Munda.

With the 2-week battle of Munda Point lost, the Japanese abandoned New Georgia entirely and redeployed to adjacent Kolombangara Island and Vila, Munda’s satellite airfield. The Kolombangara garrision, enlarged by 3,400 survivors from New Georgia, lay prostrate under continual U.S. air strikes and interdiction. Over 10,000 troops were evacuated piecemeal by Japanese destroyers, assault boats, and barges between late September and early or mid-October 1943. On September 25, 1943, a few U.S. soldiers landed on Kolombangara and established a defense perimeter around Vila airfield. Funnily enough, in January 1944 a fresh vegetable farm was planted on the abandoned airstrip.

Marching Through the New Georgias: The New Georgia Campaign, June 21 to October 7, 1943

|

Above: At At 45 by 35 miles/72 by 56 kilometers in size, New Georgia Island is the largest of 11 main islands in the Central Solomons. The terrain of the New Georgia group of islands is typical of many South Pacific islands, with thick, trackless rain forests covering volcanic cores. Inlets, lagoons, and channels dot the coastline. Landing beaches suitable for LCIs (landing craft, infantry) are few. A difficult climate, torrential rainfall, and tenacious mud plagued the combatants. The Japanese had built a well-camouflaged airfield and base at Munda Point, site of a coconut plantation on New Georgia Island’s northwestern tip (center of map), and a secondary airstrip, Vila, on nearby Kolombangara Island. The New Georgia Campaign was concerned chiefly with seizing Munda airfield, a refueling station for Japanese aircraft on their way to and from Japan’s main base north of the Solomons at Rabaul on New Britain Island in Papau New Guinea. After a 2‑month campaign in the summer of 1943, the resourceful but heavily outnumbered, outgunned, and battle-scarred Japanese were forced to retreat from New Georgia Island. (Map source: Salmaggi and Pallavisini, 2194 Days of War, 1988, p. 381.)

|  |

Left: Riding in assault craft, soldiers and medics of the U.S. 43rd Infantry Division land on a New Georgia beach, to be met by native guides.

![]()

Right: U.S. Marine Raiders fire at enemy snipers hidden in the dense foliage at one of New Georgia’s landing beaches. The Japanese extracted a high price for every yard of ground lost to the enemy and vice versa. Added to the high number of wounded and missing casualties during the New Georgia campaign were 1,195 Americian dead (6 percent loss rate) against 1,671 Japanese dead (16 percent). Marine Raiders suffered a disproportionate 20 percent casualty rate due to negligible air and inaccurate artillery support.

|  |

Left: Marines Raiders cross a stream during their advance on Enogai Point, New Georgia Island. The collapse of Enogai’s defenses on July 10, 1943, prevented the enemy from heavily reinforcing the Munda area from neighboring Kolombangara Island. However, a shortage of rations and drinking water, extreme heat, humidity, disease, near continuous jungle combat, and a stubborn, well-camouflaged enemy in hardened positions took a heavy toll on American troops everywhere on New Georgia.

![]()

Right: A soldier of the U.S. 43rd Infantry Division uses an M2 flamethrower against a Japanese pillbox during fierce fighting near Munda airfield on New Georgia Island. Enemy machine-gun positions were impervious to light infantry weaponry. Japanese soldiers and marines fought skillfully, for a time forcing a stalemate at the airfield.

|  |

Left: A U.S. Army 155mm “Long Tom” gun on Rendova Island bombards enemy positions in and around the Munda airstrip. This photo shows smoke from an exploding bomb dropped by a Japanese fighter operating out of Rabaul that just missed hitting the U.S. artillery piece.

![]()

Right: Three Marine M3 “Stuart” light tanks, working alongside Army infantrymen, perform mop-up duties near Munda airfield, August 6, 1943, 1 day after Americans finally took their main objective. Munda’s defenders, ordered by the Japanese Imperial Staff in Tokyo to defend the airfield to the last man, knocked out several tanks before being overrun themselves. Some enemy soldiers resorted to holing up in caves; others joined the retreat to Kolombangara Island. Major ground fighting on New Georgia ceased on August 23.

New Georgia Campaign, 1943: Rendova Island to Munda Airfield

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click