U.S. GOVERNMENT BEGINS ARRESTING ENEMY ALIENS

Washington, D.C. • December 8, 1941

Although the devastating Japanese surprise attack on U.S. military installations at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on December 7, 1941, came as a shock to most Americans, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration had already begun weighing possible responses to an outbreak of war with Japan, Germany, and Italy—countries treaty-bound in a mutual defense pact, the Tripartite (or Axis) Pact. One response focused on what to do with the over 110,000 Japanese-born (Issei) and first American-born generation Japanese (Nisei) living along the Pacific coast of California, Oregon, and Washington. Naval and aircraft manufacturing facilities, hydroelectric dams, power stations, bridges—all of them unguarded—appeared vulnerable to attack by Japanese fifth columnists, U.S.-based clandestine enemy agents bent on internal subversion and havoc-making. Prescient West Coast Japanese Americans speculated as early as 1937 over whether they and Japanese Issei (mostly long-term U.S. residents who were denied U.S. citizenship by discriminatory laws) might one day be “herded into prison camps” in the event of war with Japan.

Japanese Americans were not the only potential fifth columnists mentioned in the popular press and weighing on the minds of the average American. Playing no favorites, Washington lawmakers passed the anti-alien Smith Act, also known as the Alien Registration Act of 1940. Signed into law by Roosevelt on June 28, the law prohibited certain subversive activities, amended provisions for entry and deportation of aliens, and required fingerprinting and registration of non-citizen residents over 14 years of age. The Federal Bureau of Investigation compiled a list of potentially dangerous or subversive Japanese, German, and Italian aliens who were to be arrested and interned at the outbreak of war with their country. Some West Coast communities were placed under surveillance.

So it was on this date, December 8, 1941, the day the U.S. Congress declared war on the Empire of Japan, that the U.S. Justice Department and FBI swung into action, arresting 3,000 people from all over the country whom they considered dangerous enemy aliens. Only half were Japanese. (It was 3 days later before Congress declared war on Japan’s military partners, Germany and Italy.) Late the next month many of those arrested by the FBI (now 4,000 and growing) were deported to distant internment camps run by Justice’s Immigration and Naturalization Service at Fort Missoula in Montana, Fort Stanton in New Mexico, and Fort Lincoln in North Dakota. Eventually over 7,000 people of Japanese origin were held in these and similar camps.

Most Issei, now classified as “enemy aliens,” and American-born Nisei, now classified curiously as “non-aliens,” who were snapped up by government agents in December 1941 and through the following March were transferred over the course of 1942 to 1 of 10 confinement sites run by the War Relocation Authority, a civilian organization created on March 19, 1942, following Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 of February 19, 1942. That order authorized the Secretary of War and his military commanders to remove all individuals of Japanese ancestry from designated “military areas” and confine them in camps behind barbed wire for the duration of the war. FDR’s order was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in Korematsu v. United States on December 18, 1944. In a 6–3 decision the court held that the exclusion order and the incarceration of Japanese nationals and Japanese-born American citizens was justified during circumstances of “emergency and peril.” In 1976 President Gerald Ford signed a proclamation formally terminating Executive Order 9066 and apologizing for the internment.

Roundup of West Coast Japanese, December 1941 to March 1942: Prologue to Wholesale Japanese American Internment

|

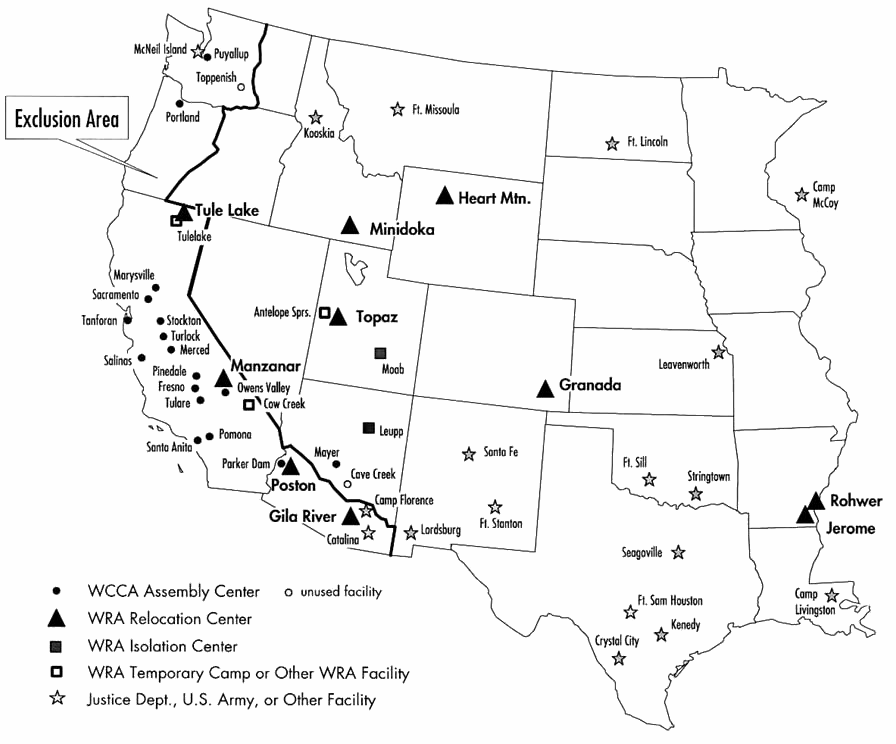

Above: Map of massive World War II exclusion area and incarceration camps in the continental U.S. for Japanese Americans as well as for over 31,000 “enemy aliens” and their families. The latter grouping consisted of collections of Germans, Italians, but also U.S.-resident Japanese Issei and Japanese and German nationals and their dependents deported from Latin America and the Caribbean. For the most part these 31,000 enemy aliens were incarcerated under the Justice Department’s Enemy Alien Control Program. The 10 incarceration camps, euphemistically called “relocation centers,” are identified by black triangles and were located in 7 states. Justice Department camps (8) and U.S. Army camps (18) are represented by stars; for example, Fort Missoula Internment Camp in Montana and Fort Lincoln Internment Camp 5 miles/8 km south of Bismarck, North Dakota. It was to these often former Civilian Conservation Corps camps that people arrested between December 7, 1941, and early 1942—that is, before Executive Order 9066 was in place—were brought. In the map legend, WCCA = Wartime Civil Control Administration, WRA = War Relocation Authority. Over 126,000 Japanese American citizens and Japanese nationals would eventually be removed from their homes in California (where the majority lived), the western halves of Oregon and Washington, and Southern Arizona, which states comprised the “exclusion area,” as part of the single-largest forced relocation/incarceration in U.S. history. The Poston War Relocation Center on the Colorado Indian Reservation south of Parker was the largest such camp in America (peak population 17,814). Housing Japanese Americans and nationals mostly from Southern and Central California, Posten became the third-largest “city” in Arizona at the time. Together with the Rivers War Relocation Center on the Gila River Indian Reservation 64 miles/103 km southeast of Phoenix, the 2 sites grew to hold 30,000 people of Japanese descent, most of them American citizens. (Some people of Japanese descent who took a loyalty oath to the U.S. government were released from confinement in 1944 and 1945. Others were not released until 1946, when over 4,400 people of Japanese descent were repatriated to Japan.) In Hawaii, where 150,000-plus Japanese Issei and U.S.-born Japanese comprised over one-third of the population, only 1,200 to 1,800 were removed to the mainland and incarcerated. On the Hawaiian island of Oahu, the location of Pearl Harbor, there were 17 incarceration sites, the largest and longest-operating being Honouliuli Internment Camp, which held 320 internees and 4,000 prisoners of war. For their own “protection,” nearly 900 indigenous Aleuts were rounded up and confined in abandoned salmon canneries near Alaska’s capital Juneau, 2,000 miles/3,219 km from their island villages, which were burned to the ground as part of a “scorched earth” policy.

|  |

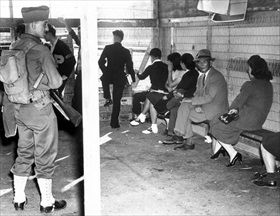

Left: “Here is a view of some of the Japanese taken into custody by FBI officers when a ferry from Terminal Island docked at San Pedro [California]. They were herded into a wire enclosure for questioning and were guarded by soldiers from Fort McArthur [sic]. . . . Terminal Island, with a Japanese colony of 6000, has become [a] huge concentration camp with aliens refused [the] right to leave confines and citizens ordered to stay home.” Newspaper caption. Photograph taken December 7, 1941? Published December 8, 1941. Source for this and the next 5 photographs and captions: University of California Calisphere. Two of the most prominent temporary detention stations holding immigrants awaiting cursory hearings before internment were Angel Island in San Francisco Bay, California, and New York’s Ellis Island. In December 1941 Ellis Island held 279 Japanese, 248 Germans, and 81 Italians.

![]()

Right: “Terminal Island Aliens Rounded Up—Male Japanese aliens, numbering some 400, residing on Terminal Island, vital naval and shipbuilding center in Los Angeles Harbor, were taken into custody early on the morning of February 2 in a surprise round-up by 180 federal, city and county officers. A group of Japanese is being loaded into an automobile after being roused from their homes.” Caption under Associated Press photograph, February 2, 1942.

|  |

Left: “This contingent of Santa Barbara County Japanese, who were rounded up in alien enemy raids under direction of FBI, [are] shown leaving county jail yesterday en route to Midwest internment camps.” Caption under Associated Press (?) photograph, February 18, 1942. Most likely the people pictured here were taken first to a detention station and then to a Department of Justice internment camp, of which there were eight. These camps were guarded by Border Patrol agents rather than military police, which provided security for the 10 WRA confinement sites.

![]()

Right: “Alien Japanese Taken Into Custody—Among a group of alien Japanese taken into custody by Federal agents in Vallejo [California] yesterday were Isekichi Matesuyama, 55, (left), and Michiko Ebisu, 49, (center), both laundry workers, shown being booked at the police station by Inspector Ralph Hensen. The pair are being held for immigration authorities.” Caption under photograph, February 18, 1942.

|  |

Left: “Japanese Seized in Roundup—Japanese aliens taken into custody by FBI agents in a surprise raid in the Santa Maria-Guadalupe area February 18 are unloaded from an Army truck at the courthouse at Santa Barbara, California, where they were brought for examination. More than 200 were taken in the roundup, and a score of Army trucks were used to transport the prisoners.” Caption under photograph, February 19, 1942.

![]()

Right: “Arrested yesterday during the sweeping Southland raids, these three smiling Japanese are shown in custody. They are, left to right, Frisco Tokichi Hasegawa, retired dry goods man; Mrs. Iku Onodesa and Tadasu Iida, teachers.” Caption under photograph, March 14, 1942. The photograph appeared in the Los Angeles Examiner.

Disingenuous 1942 Government-Produced Film Defends Internment of Japanese Americans During World War II

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click