U.S. DECLARES WAR ON JAPAN

Washington, D.C. • December 8, 1941

At 12:30 p.m. on this this rainy and blustery day in 1941, standing before a joint session of the U.S. Congress and a world listening by radio, the 32nd President of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt, laid several typewritten sheets on the speaker’s podium. The day before, the president had calmly and decisively dictated to his secretary a draft request to Congress for a declaration of war against the Empire of Japan. He had composed the speech in his head after deciding on a brief, uncomplicated appeal to the people of the United States rather than a thorough recitation of Japanese perfidies leading up to their savage attack on the unsuspecting U.S. Pacific Fleet anchored at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

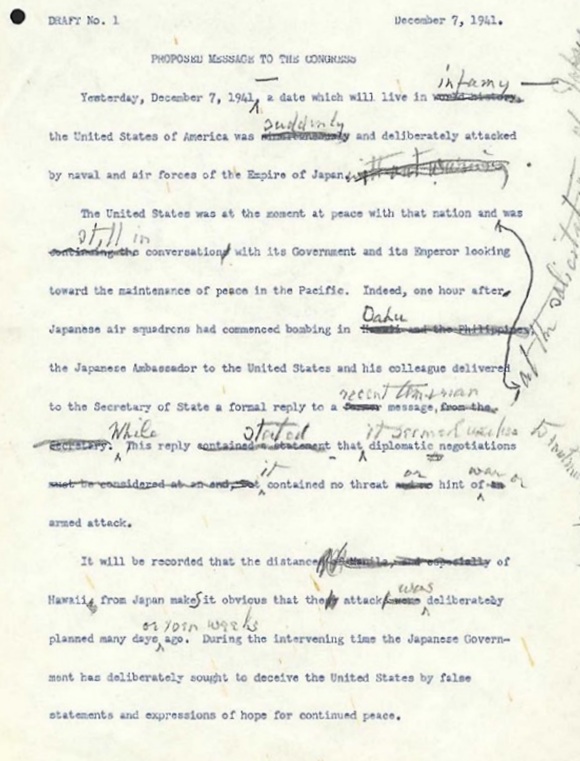

Roosevelt pencil-edited his reading copy, making the most significant change in the opening line. “Yesterday, December 7, 1941,” the president intoned in his seven-minute address to members of Congress, was “a date which will live in infamy.” Less than an hour after FDR’s speech, which was followed by five minutes of applause, shouting, and foot stamping, Congress passed a formal declaration of war against Japan and officially brought the U.S. into World War II. That same day the president wrote to British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, telling him that the two nations were in the “same boat” now, “a ship which will not and cannot be sunk.” Also on that day Britain declared war on Japan, followed within three days by at least eight more nations.

The December 7, 1941, carnage generated a visceral hatred of the Japanese in the nation’s psyche that persisted to the end of the war and beyond. Late on Monday, December 8, the U.S. aircraft carrier Enterprise, calling off its hunt for the Japanese marauders, maneuvered through the Pearl Harbor channel to park at Carrier Row on the opposite side of Ford Island’s Battleship Row. After viewing the battered and scorched Pacific Fleet from his flattop—a black and red inferno lighting the evening sky as fires continued consuming the USS Arizona, the air reeking of leaking fuel oil and smoke, the harbor waters mottled with flotsam—Adm. William “Bull” Halsey uttered his memorable curse: “Before we’re through with ’em, the Japanese language will be spoken only in hell.”

![]()

The Day After Pearl Harbor

|

Above: Page 1 of President Roosevelt’s changes to his first draft of the “Day of Infamy” speech delivered to the U.S. Congress on December 8, 1941. The five hundred word address is regarded as one of the most famous American political speeches of the 20th century.

|  |

Left: President Roosevelt delivers his “Day of Infamy” speech to members and guests of the U.S. Congress, December 8, 1941. Behind him are Vice President Henry Wallace (left) and Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn. To the right, in military uniform in front of Rayburn, is Roosevelt’s son James, who escorted his father to the Capitol. Only one member of Congress, a life-long pacifist from Montana, voted against the declaration of war. The anti-war and isolationist movement that had campaigned so strongly against American involvement in the war in Europe, begun in September 1939, collapsed almost immediately on the day Adolf Hitler’s and Benito Mussolini’s Axis partner, Japan, launched a preemptive strike on U.S. facilities at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

![]()

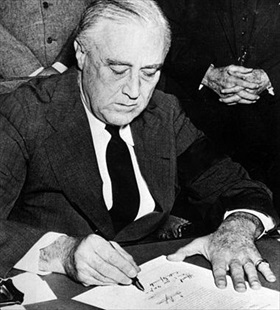

Right: A grim-faced President Roosevelt signs the declaration of war against Japan, December 8, 1941. That Monday and for days afterwards U.S. recruiting stations were jammed with a surge of volunteers and had to go on 24‑hour duty to deal with the crowds seeking to enlist in the armed forces. Famous American aviator Charles Lindbergh, the nation’s leading isolationist, made a 180-degree turn, declaring: “Our country has been attacked by force of arms, and by force of arms we must retaliate. We must now turn every effort to building the greatest and most efficient Army, Navy and Air Force in the world.”

President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Address to U.S. Congress, December 8, 1941

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click