U.S.-AUSTRALIAN AIRMEN MAUL JAPANESE CONVOY

Bismarck Sea, Southwestern Pacific Ocean • March 2, 1943

The Battle of Midway (June 4–7, 1942) was America’s first strategic victory against the Japanese Navy and a devastating defeat for the warlords ruling that Asian nation. Lost were 4 of the 6 Japanese aircraft carriers (the bulk of the Japanese carrier fleet) that had taken part in the sneak attack on the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on December 7, 1941. Midway is considered the turning point in the Pacific War, despite Japan still maintaining a powerful presence throughout Southeast Asia, especially in New Guinea and the Solomon Islands in the latter half of 1942–early 1943 (see map below), islands that lay at the doorstep of Australia, America’s threatened ally against expansionist Japan.

Often denied its turning-point status, the Battle of Bismarck Sea was a repeat mauling by U.S. armed forces on Japanese interests in the Southwest Pacific, this time assisted by Australian servicemembers. In early February 1943 U.S. naval codebreakers decrypted enemy signals that a large Japanese convoy was forming to land more than 9,000 fresh troops at Lae on the south side of the Huon Peninsula of New Guinea. Several months before, the 2 Allies had wiped out Japanese invaders at Buna and nearby Gona, Australian-Papuan settlements over 160 miles/257 kilometers south of Lae. The enemy convoy was to leave Rabaul, Japan’s strategic naval and army stronghold on the eastern tip of New Britain Island, steam to the western end of that island, pass south through the Vitiaz Strait toward Finschhafen, and steer west into the Huon Gulf. A successful Lae landing would provide the enemy with sufficient reinforcements to allow them to reclaim the initiative in New Guinea, or so it was thought.

In late February 1943 a Japanese convoy of 8 destroyer escorts, 7 troop transports and a naval special service ship carrying more than 6,000 ground troops and aviation personnel, plus a protective screen of 100 aircraft, was assembling at Rabaul. Meanwhile, Australia-based crews of U.S. and Australian bomb groups reporting to U.S. Fifth Air Force Maj. Gen. George Kenney were refining their killer skills. (Kenney reported directly to Gen. Douglas MacArthur, supreme military commander in the Southwest Pacific Theater, which included the territories of Papua and New Guinea and the western part of the Solomon Islands.) The killer skills being honed were skip-bombing skills as a means of sinking or damaging enemy vessels. The idea was for a bomber to release its deadly payload at extremely low altitude (masthead height) so that it skimmed across the water like a flat rock before striking the side of its target. Practice results were spectacular.

Of course, proof was in the battle. On this date, March 2, 1943, and over the next 2 days, squadrons of Consolidated B‑24 Liberators, Martin B‑26 Marauders, Douglas A‑20 Havocs, North American B‑25 Mitchells, preceded by U.S. and Royal Australian cannon-fighter and torpedo bomber aircraft, strafed, bombed, and skip-bombed enemy ships. Off Lae on the second day Allied air forces fell on the surviving foe. Diary entries of Japanese sailors and soldiers describe ship decks awash in blood. By the time the high-altitude bombers and the low-flying A‑20 and B‑25 skip-bombers had left the gruesome fray, 7 troop transports, 6 or 7 destroyers, and almost 3,000 Japanese had slipped below the green surface of the Bismarck Sea or clung to flotsam. Returning U.S. pilots and Navy fast (PT) boats were ordered to completely riddle every soldier (about 1,000) and box of supplies still floating in the water, which they tried doing. The last troop transport, a derelict, was dispatched to the seabed on March 3. Some 2,700 enemy survivors were picked up by rescue destroyers and submarines during and after the killing spree and returned to Rabaul; only about 1,200 ever reached Lae. Allied losses over the 3 days were 13 aircrew, 4 fighter aircraft, and 8 wounded.

Japanese Calamity: The Battle of the Bismarck Sea, March 2–4, 1943

Above: The Battle of the Bismarck Sea (March 2–4, 1943) involved no U.S., Australian, or Japanese warships with the exception of Japanese destroyers escorting troop transports and U.S. Navy PT boats providing mop-up services. Nevertheless, the Battle of the Bismarck Sea counted as both a major World War II naval battle and a major turning point in the Pacific War in the way that the Battle of Midway did three-quarters of a year earlier. The success of the American and Australian aircrews vividly demonstrated that the claims put forth by U.S. Brig. Gen. Billy Mitchell in the early 1920s, namely, that land-based bombers were a highly effective weapon against enemy ships, were indeed true. Japanese hopes for regaining the initiative on the island of New Guinea (today Papua New Guinea) after the Battle of the Bismarck Sea were dashed when the remaining and starving Japanese garrisons succumbed to amphibious and land-based offensives by U.S. and Australian troops and airmen under the leadership of Gen. Douglas MacArthur. |

|  |

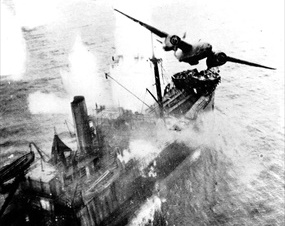

Above: In the left frame a Japanese troop transport is under aerial attack in the Bismarck Sea, March 3, 1943. The troop convoy carried the main body of the Japanese 51st Infantry Division from Rabaul, the Japanese stronghold on New Britain Island, to Lae in Northeast New Guinea. The 51st Division was assigned to the Japanese 18th Army, whose garrison headquarters was on New Guinea. According to one source, in the Battle of the Bismarck Sea the 51st Infantry Division lost 3,664 men; only 2,427 men of the division were rescued. In the right frame a stricken Japanese vessel billows smoke from a bomb hit amidships while a fire rages in the stern. Moments later the transport settled on the bottom of the sea.

|  |

Left: A U.S. Douglas A-20 Havoc at the moment it cleared a Japanese merchant ship following a successful skip-bombing attack. A more successful anti-shipping technique was mast-height, or extreme low altitude, bombing. The 2 techniques were not mutually exclusive, however. Aircrew could deliver their first bomb by skipping it and the second at mast height.

![]()

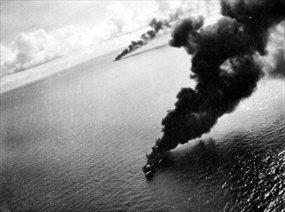

Right: Aerial photograph taken on March 3, 1943, of Japanese ships on fire after an attack by Bristol Beaufighters of No. 30 Squadron Royal Australian Air Force. According to the official RAAF release on the Beaufighter attack, “enemy crews were slain beside their guns, deck cargo burst into flame, superstructures toppled and burned.” By day’s end 7 transports had been hit and most were burning or sinking along with 3 escort destroyers. Four other enemy destroyers picked up as many survivors as possible and then fled to Rabaul, accompanied by a fifth destroyer that had been sent from Rabaul to assist in the rescue. On the evenings of March 3–5, a slew of U.S. aircraft and Navy PT boats raked Japanese rescue vessels, as well as the shipwreck survivors on life rafts and swimming or floating in the sea. The murderous runs were later justified on grounds that rescued Japanese servicemen would have been rapidly landed at their military destination and promptly returned to combat, as well as retaliation for Japanese pilots shooting U.S. survivors of downed aircraft.

|  |

Left: Mast-height bombing required bombers to approach a target ship at low altitude, 200–500 ft/61–152 m, at roughly 265–275 miles/426–442 kilometers per hour, and then drop down to mast height, 10–15 ft/3–4.6 m about 600 yards/549 m from the target. The aircraft released its bombs around 300 yards/270 m short of the target, aiming directly at it, preferably broadside. In this photo, sweeping in at mast height, 2 U.S. medium bombers, probably Mitchell B‑25s, prepare to drop their payload on a Japanese troop transport, possibly the Taimei Maru.

![]()

Right: U.S. Fifth Air Force bombs bracket the 2,883‑ton transport Taimei Maru, March 3, 1943. The transport carried a cargo of troops, equipment, fuel, landing craft, and ammunition destined for Lae on New Guinea. Of the men aboard, some 200 perished in the attack. An airborne and seaborne assault by U.S. and Australian forces on Lae in mid-September 1943 in led to the destruction of Japanese efforts in New Guinea.

Newsreel Account of the Battle of the Bismarck Sea, March 2–4, 1943

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click