U.S. ARMY LAUNCHES BOUGAINVILLE CAMPAIGN IN SOUTHWEST PACIFIC

Cape Torokina, Bougainville, Northern Solomon Islands • November 1, 1943

Guadalcanal, the largest island in the southern Solomon Islands, was the site where the string of Japanese conquests, starting in Janunary 1942, finally ran its course. The bloody fight for Guadalcanal (August 7, 1942 to February 9, 1943) was a recognized turning point in the Pacific War. That said, the long island-hopping road from Guadalcanal via Bougainville in the Solomon Islands to the Bismarck Archipelago, to the large island of New Guinea, to the Caroline and Mariana island groups and the Philippines, then on to Tokyo Bay was 3 years in duration and would require fighting a stubborn foe across countless jungle-clad islands and over huge expanses of mostly empty ocean.

The Bougainville Campaign, codenamed Operation Cherryblossom, launched on this date, November 1, 1943, was a subordinate series of closely coordinated land and naval operations in the Allied grand strategy known as Operation Cartwheel (1943–1944). The strategy entailed bypassing and physically isolating fortified Japanese positions in the Western Pacific and seizing weakly defended but strategically important ones—in the words of U.S. Gen. Douglas MacArthur, Allied Supreme Commander, Southwest Pacific Area: “Hit ’em where they ain’t.” Actually, Cartwheel’s ultimate goal was to isolate (“neutralize” or “reduce” in the language of the day) Rabaul, the key Japanese air, land, and naval bastion on New Britain Island in the Bismarck Archipelago, less than 200 miles/322 km north of Bougainville Island, the largest island in the Solomons chain. Rabaul, bristling with enemy warships and warplanes, menaced the lanes of sea and air communications between the U.S. and its chief allies in the Southwest Pacific, Australia and New Zealand, and it blocked any Allied drive to expel the enemy from New Guinea’s Papuan Peninsula and the Philippines.

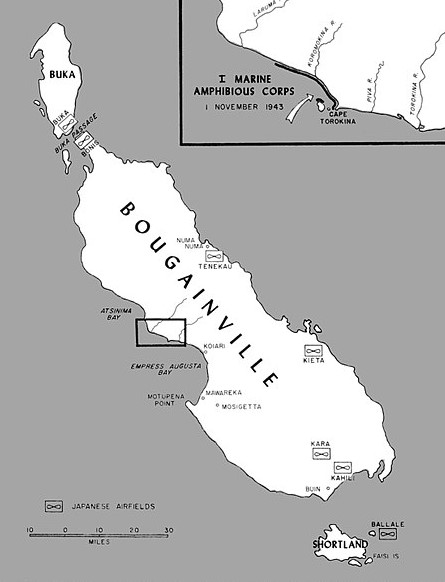

The Bougainville Campaign was divided into 2 phases, one under formal American command, the other under Australian command. The first phase, which ended in November 1944, was kicked off by 14,000 U.S. Marines landing and building a strong defensive perimeter around the beachhead at Cape Torokina in Empress Augusta Bay on the west side of Bougainville Island (see map). By late November/early December, 3 airstrips had been established inside the perimeter from which to project airpower toward Rabaul. The last airstrip, one suitable for bomber runs, became fully operational at the end of January 1944. These airstrips played an important role in isolating Rabaul, now under daily bombardment from Bougainville and airbases further south. Throughout 1944 and 1945, follow-on forces from the U.S. Army and then the Australian II Corps arrived as the Allies conducted operations to clear and secure the rest of the island.

Even before the U.S. role in combat wound down, the possession of Bougainville by either side in the conflict was of no consequence to the outcome of the Pacific War. The shorter second phase of combat operations saw just over 30,000 Australian troops going on the offensive—ferreting out remnants of beaten, starving, disease-ridden, and die-hard Japanese soldiers from holes and bunkers that laced the island. Phase 2 was nearly as protracted as the first, lasting until August 21, 1945. It was certainly more deadly. In those last 10 months Japanese KIA’s (killed-in-action) numbered 8,500 out of an estimated 18,500–21,500 dead overall. Of the enemy dead, tropical diseases and debilitating malnutrition carried off about half of them: 9,800. Surviving combat were some 21,000–23,500 Japanese and Korean laborers. Australian casualties exceeded 2,000 dead and wounded; U.S. dead amounted to 727. On the civilian side potentially 13,000 of the pre-war population of 52,000 died, with most islanders’ deaths occurring after 1943.

The Bougainville Campaign and the Allied Plan to Isolate the Strategic Japanese Fortress at Rabaul in the Southwest Pacific

|

Above: Map

depicting Japanese bases and the narrow U.S. Marine invasion beaches on the west coast of Bougainville Island at Cape Torokina, November 1–2, 1943. Administered by Australia before March–April 1942, when the Japanese seized the island during their advance into the South Pacific, Bougainville had a pre-war population of 52,000. At 3,591 sq. miles/9,300 sq. km, the fiddle-shaped island (75 miles/121 km long and 40–60 miles/64–96 km wide) of thick jungle and large mountain peaks in its interior is slightly larger than the U.S. state of Delaware. Once secured, the Japanese began constructing a number of airfields across the island—at Buka Island in the north, at Kahili and Kara in the south, and Kieta on the east coast—along with a naval anchorage near Buin. These bases helped protect Rabaul, Japan’s major garrison and naval base on New Britain Island in neighboring Papua New Guinea, making Bougainville an attractive Allied objective. After the war Bougainville was returned to Australian administration as part of the U.N. Trust Territory of New Guinea. When Australia granted independence to Papua New Guinea in 1975, Bougainville became the easternmost province of that new country.

|  |

Left: Landing craft carrying men and equipment of the 3rd Marine Division (a formation of the I Marine Amphibious Corps) form a circle in Empress Augusta Bay while awaiting landing orders during the invasion of Cape Torokina, Bougainville, November 1–2, 1943. The invasion beaches, 5,000 yards/4.6 km in the background, are being shelled by U.S. destoyers to little effect. In the far distance is one of two active island volcanoes, Mount Bagana, rising 8,650 ft/2,636 m above sea level and belching smoke.

![]()

Right: Men from the 1st Battalion, 3rd Marine Division on Blue Beach 3 shortly after their landing. Marines mostly met limited resistance from the enemy, their landing on the island’s western coast having come as a surprise to the Japanese defenders. Enemy aircraft from Rabaul attempted to interdict the landing force, but their attacks proved ineffective and they were largely fought off by U.S. and New Zealand fighter aircraft for a loss of 26 Japanese planes. By the end of the first day, a small defensive perimeter had been established and the majority of the first wave of transports had unloaded their stores on the beachhead. A week later some Marine elements were able to take the offensive.

|  |

Left: These Marines gathered for a group photograph in front of a Japanese dugout at Cape Torokina, which they helped take. Within 4 to 6 weeks of their landing, the Marines and soldiers of the U.S. 37th Infantry Division had expanded their perimeter to a depth of 6 miles/9.7 km or so, established 3 airstrips (courtesy of Navy Seabees) from which to bomb Rabaul several hundred miles/kilometers to the northeast, and essentially isolated the enemy defenders, though the Japanese still had a substantial number of army (40,000) and naval (20,000) personnel in the southern part of the island to harass the Americans.

![]()

Right: Japanese troops tried infiltrating Allied lines at night. At dawn U.S. soldiers would clear them out. In this photo, taken during the Battle of the Perimeter (March 9–27, 1944), an M4 Sherman tank covers advancing infantrymen. Japanese casualties during the 2‑1/2-week battle were estimated to have been 5,400 killed and 7,100 wounded. In its aftermath and cut off from outside assistance, the enemy withdrew the majority of its forces into the jungle interior and to the north and south ends of the island, where those not swept up by aggressive Australian patrols (Phase 2) or swept off by malnourishment or tropical diseases maintained a precarious existence until the end of the war.

U.S. Army Presentation: “Bougainville: A Step to Victory” (1943–1944)

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click