U.N. RELIEF AND REHABILITATION ADMINISTRATION CREATED

Washington, D.C. • November 9, 1943

On this date in 1943 in Washington, D.C., U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt added his signature to an agreement by representatives of 44 nations to establish the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. UNRRA (pronounced un-ruh) was the first U.N. organization to be created, established 1½ years before the United Nations charter itself was agreed to by 50 member states on June 26, 1945.

UNRRA’s operations focused on 3 humanitarian service areas on 6 continents. Services were (1) arranging and/or distributing relief supplies such as food, shelter, clothing, medicine, fuel, farm implements, and other basic necessities, (2) arranging and/or providing relief services through a cadre of trained staff to which all signatory nations contributed, and (3) aiding agricultural and economic rehabilitation. The U.S. government provided nearly three-quarters of UNRRA’s funding, or $2.7 billion. Over 125 nongovernmental and private charitable aid societies and civic and religious organizations assisted UNRRA’s staff of 12,000 people with donations, auxiliary personnel, and a myriad of other social welfare services such as help locating relatives who had survived enemy work, concentration, and death camps as well as providing resettlement and repatriation assistance; increasingly, the organizations operated independently of UNRRA.

To facilitate their services UNRRA joined with Allied authorities to establish and maintain nearly 800 resettlement camps housing over 700,000 people (1947 figure) in Germany, Austria, Poland, Italy, Yugoslavia, Greece, and other strife-torn countries, including 4 countries in Asia. UNRRA camps distributed foodstuffs and medicines; sheltered millions upon millions of vulnerable men, women, and children; repatriated millions of refugees; and provided economic and vocational assistance to those who fell under their care even before the global conflict ended. These at-risk people fell into 2 broad categories—displaced persons (DPs) and refugees. Displaced persons were those beings who fled actual or potential conflict areas, often by the skin of their teeth, mostly destitute, and suffering the consequences of being uprooted. These included millions of people consigned to forced labor in mines and factories or on farms in Nazi Germany. Interned in assembly centers or displaced persons camps, DPs could be expected to return to their native countries when hostilities ceased. Refugees on the other hand were involuntary migrants who were rendered homeless, having been evicted, exiled, or deported, unwilling or unable to return home (“non-repatriables”) and hence existed outside the protection of their former government; these stateless victims were interned in refugee camps. Generally speaking, “DP” covered both categories of people.

European Jewry presented a unique and dire picture. It constituted 25 percent of the DP population. Months after liberation the majority remained under military guard behind barbed wire in camps where they were found, suffering from shortages of food, clothing, medicine, good sanitation, and all sorts of supplies. Death rates remained high. Between 1945 and 1952, more than 250,000 Jewish displaced persons lived in camps and urban centers in Germany, Austria, and Italy alone.

UNRRA was dissolved in September 1948. Its work was taken over by U.N. successor organizations and specialized agencies, among them the International Refugee Organization (IRO) working on behalf of 643,000 displaced persons and refugees (1948 figure), by the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) and the World Health Organization (WHO), and by the institutional machinery later created by the U.S. Marshall Plan after 1948. But in the crucial years 1943–1948, when many millions of civilians were most vulnerable, dozens of generous nations and hundreds of agencies mobilized whatever resources they had or could put their hands on to help feed the hungry, clothe the destitute, nurse the sick and wounded to health, send them on their way, and heal a broken world.

Life in Postwar Displaced Persons Camps

|  |

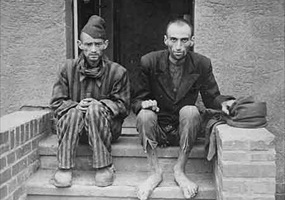

Left: Two emaciated Jewish survivors, cheekbones prominent in their faces, sit outside a barracks in newly liberated Dora-Nordhausen (aka Dora-Mittelbau) concentration camp, mid-April 1945. In displaced persons camps like the converted Dora-Nordhausen camp Holocaust survivors who had survived years in hiding, or in ghettos, or in concentration and death factories often lived among anti-Semites and unrepentant and vindictive Nazi sympathizers and collaborators who had harassed, persecuted, and killed Jews before and during World War II. This was especially true of camps containing refugees and displaced people from Central and Eastern Europe (Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Hungary, and Romania). In the summer of 1945, Earl Harrison, U.S. President Harry S. Truman’s emissary to the DP camps, wrote a report on the Jews’ suffering in the camps. The result: in the U.S. zone of occupied Germany Jewish refugees were transferred from camps organized by countries of nationality to separate camps where U.S. Jewish relief organizations and Zionist activists from Jewish Palestine could operate. Conditions improved immeasurably.

![]()

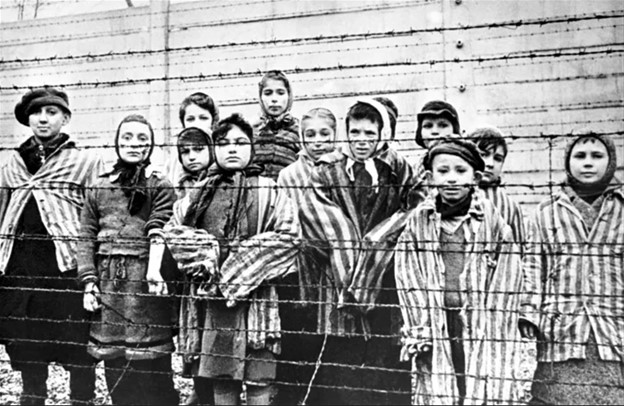

Right: Child survivors at Auschwitz on liberation day, January 27, 1945. Between 1.1 and 1.3 million prisoners (perhaps more), or about 85 percent of the people sent to Auschwitz, were murdered at the Auschwitz-Birkenau complex in what is today Southwest Poland, the epicenter of one of mankind’s darkest acts. During the complex’s nearly 5‑year existence an estimated 232,000 children and young people up to the age of 18 were among the millions killed. The figure includes roughly 216,000 Jews (majority Hungarian), 11,000 Roma (Gypsies), at least 3,000 Poles, and over 1,000 Belarusians, along with a significant number of Russian and Ukrainian children. On a single day in late 1944—October 10, 1944—800 children were gassed to death. The majority of the innocents were deported to Auschwitz along with their parents in various campaigns directed against whole ethnic, religious, or social groups.

|  |

Left: One of the many responsibilities UNRRA workers assumed was assisting military authorities in caring for millions of refugees in resettlement camps and repatriating displaced persons. This picture shows a Polish displaced person being registered at Buchenwald. The U.S. Army converted the former German concentration camp near Weimar in Thueringen (Thuringia) state into a reception center for displaced persons who surfaced in the neighborhood. Photo taken between 1945 and 1947.

![]()

Right: A Polish UNRRA worker registers information from a displaced man and his wife, perhaps newly repatriated. The photo caption says, “He will receive a further credit of up to 10,000 złotych for the purchase of livestock and tools when he is assigned his farm.” The victorious Allies awarded large areas of Prussia, Pomerania, Saxony, and Silesia, former German territories, to Poland at the Potsdam Conference (July 17 to August 2, 1945) as Poland’s prewar borders in the east and west were forcibly shifted westward. That uprooted 13.5 million ethnic Germans. Upwards of 4 million Poles were uprooted from areas that became parts of Soviet-annexed Lithuania, Belorussia (Belarus), and Ukraine. Photo taken between 1945 and 1948.

|  |

Left: Ibby Neuman and Max Mandel’s wedding day at the Bad Reichenhall DP camp, Germany, February 22, 1948. Displaced persons transformed the camps into active cultural and social centers. Despite the often-bleak conditions—many of the camps were former German army camps or concentration camps—social, occupational, and vocational organizations abounded. Academic, vocational, and religious schools were established and teachers came from North America and Israel to teach children and adults. Orthodox Judaism began its rebirth as yeshi (religious schools). Jewish DPs became an influential force in the Zionist cause and in the political debate about the creation of a Jewish state. Journalism sprang to life with more than 170 publications, many in Yiddish. Numerous theater and musical troops toured the camps. Athletic clubs from various DP centers challenged each other. Religious holidays and events, births, and weddings became major occasions for gatherings and celebrations.

![]()

Right: In the first months after the war there were barely any children under the age of 5 in the DP camps and only 3 percent of Jewish survivors were children and teenagers aged 6–17. Most survivors of Nazi camps had lost their entire families through gassing, phenol injections, diseases like typhus, starvation, and death marches. Displaced persons, refugees, UNRRA personnel, and relief agencies placed a premium on establishing camp schools where food and books from outside could feed and rebuild the lives of the younger generation. For Jewish survivors especially it was important to raise a new generation of Jews to make up for those who had been wiped out by the Nazis.

Holocaust Survivors–First Steps in the DP Camps and a New Beginning

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click