TRUMAN URGED NOT TO USE A-BOMB ON JAPAN

Chicago, Illinois · July 3, 1945

On this date in 1945 Hungarian-born physicist and inventor Leó Szilárd drafted the first of two versions of a petition to President Harry S. Truman, urging him not to use the atomic bomb on Japan before that nation had been given a chance to surrender. It was Szilárd who, in 1933, had conceived the nuclear chain reaction and patented the idea of a nuclear reactor with Italian-born Enrico Fermi. And it was Szilárd who, in July 1939, wrote the letter for Albert Einstein’s signature that resulted in the Manhattan Project, which built the atomic bomb. By 1945, however, Szilárd was firmly convinced that using a nuclear weapon on Japan would carry the world further down a path of ruthlessness that began with Germany raining bombs on Polish and British cities in the early days of the war. In reaction to the final version of the petition, signed and dated July 17, 1945, by 70 leading scientists who were involved in the atomic bomb research project, Brig. Gen. Leslie Groves, the director of the $2 billion-plus Manhattan Project, unsuccessfully sought evidence of Szilárd violating the U.S. Espionage Act. Most of the signers were punished by losing their jobs in weapons work. In the meantime, on August 6, 1945, a specially modified B‑29 Superfortress named Enola Gay dropped the first of two atomic bombs on Japan, “Little Boy,” a five-ton bomb of which less than a kilogram underwent nuclear fission. Yet “Little Boy” produced enough energy to kill more than 90,000 citizens of Hiroshima outright and injure over 37,000, many of whom would die later from the effects of radiation. Three days later Bockscar, another modified B‑29, exploded a second atomic bomb, “Fat Man,” over Nagasaki, 260 miles to the south, killing 40,000–75,000 people. By the end of 1945 total deaths in Nagasaki may have reached 80,000. Both atomic bombs destroyed 50 percent of each city. Indeed, an estimated 40 percent of Japan’s built-up cities were devastated in U.S. air attacks in 1944–1945. On August 14, 1945, when Emperor Hirohito (posthumously referred to as Emperor Shōwa) announced to the Imperial Council his personal decision to accept the Allies’ terms for Japan’s unconditional surrender, World War II was suddenly over—a war that had engaged the U.S. for three years and eight months and had killed 405,399 Americans and wounded 670,846.

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”ASINList” width=”600″ height=”200″ title=”Recommended Reading” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”False” show_border=”False” asin=”0060742852,087332773X,0141001461,0807845477,1579128084,080785607X,0306801892,067976285X,0316831247,1936274000″ /]

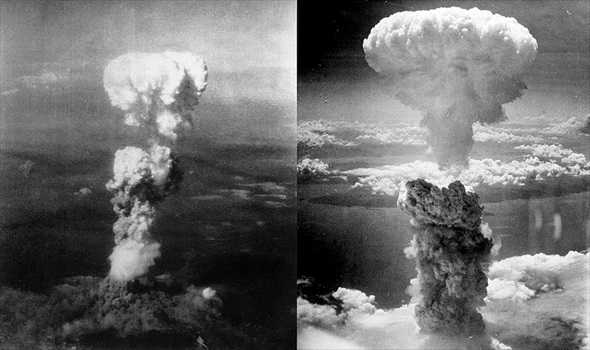

Dawn of the Atomic Age: Hiroshima and Nagasaki, August 6 and 9, 1945

|

Left: At the time this photo was made, August 6, 1945, a column of radioactive smoke billowed 20,000 feet above Hiroshima while smoke from the burst spread over 10,000 feet from the base of the rising column. Bad weather disqualified a target, as scientists insisted on a visual delivery of the atomic bomb. The primary bombing target on August 6 was Hiroshima. Secondary and tertiary targets were Kokura and Nagasaki, respectively.

![]()

Right: Atomic bombing of secondary target Nagasaki, August 9, 1945. Cloud cover over Kokura, the primary target that day, inhibited a visual attack. A last-minute break in the clouds over Nagasaki doomed that city. The next day, August 10, Tokyo protested the cataclysmic bombings in a letter to the U.S. government via the Swiss embassy.

|  |

Left: Hiroshima, a metropolis of 300,000 people before the August 6, 1945, bombing. Area around ground zero. 1,000 foot circles.

![]()

Right: Hiroshima after its devastation. Area around ground zero. 1,000 foot circles.

“A Tale of Two Cities”: 1946 U.S. War Department Film Documents Hiroshima’s and Nagasaki’s Destruction

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click