TEHRAN CONFERENCE TO SHAPE POSTWAR WORLD

Tehran, Iran • November 28, 1943

On November 27, 1943, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt left Cairo for Tehran, Iran’s capital. The Egyptian capital had hosted 2 Western leaders, Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and Chinese Nationalist leader Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek. The Cairo Conference, codenamed Sextant, was a feeder conference to a weightier one with Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin in Tehran. Apart from agreeing to construct long-distance, heavy bomber bases in the China-Burma-India (CBI) Theater (eventually 4 were built in India and 4 in China) to support the war against Japan, the Cairo meeting foundered partly on Roosevelt’s opposition to Churchill’s postwar aims for restoring British hegemony in her former Southeast Asian colonies.

Arriving separately in Tehran after a 1,300-mile/2,092-km flight, the 2 Western leaders met their Soviet counterpart on this date, November 28, 1943. The Tehran Conference, codenamed Eureka, turned out to be the most significant and far-reaching top-level Allied talks on the European war so far. For one thing it was the first time the Big Three, accompanied by their military chiefs of staff and political advisors, met together in the same location. Over the next 3½ days each side presented its perspective on the progress of the war against the Axis powers (principally Germany, Italy, and Japan), how to prosecute the war to victory, what a postwar world might look like, and how to protect the peace using an international organization as a postwar watchdog.

The following day, November 29, Stalin was all ears when the 2 Western leaders and their military advisors discussed Operation Overlord, the upcoming Anglo-Canadian-American air and sea invasion of Northwest Europe. Still very much in the planning stage, the invasion had no kickoff date. For months Stalin had nagged Roosevelt and Churchill to set a date. In theory a second front in Western Europe would relieve the immense pressure Axis forces were exerting on a thousand‑mile/1,600‑km front that stretched from the Soviet Union’s second largest city, Leningrad on the Baltic Sea, south to the Soviet Crimea on the Black Sea. Stalin was relieved the next day to learn that British and American staffs had settled on May 1944 as Overlord’s launch date.

On December 1, 1944, the last day of talks, the Big Three had to confront the elephant in the room: the fates of postwar Germany and Poland. The leaders shared a consensus that Germany must be divided among the victors to neutralize that nation’s ability to wage war a third time. Over time the agreed-on divisions coalesced around a West Germany, consisting of former British, American, and French zones, and an East Germany consisting of the former Soviet zone. In October 1990 the 2 Germanys became one. With Roosevelt self-imposed on the sidelines, Churchill and Stalin addressed the question of Poland, with Churchill seeking a frontier formula he could present to the London-based Polish government-in-exile. Poland, Churchill suggested, would have the Curzon Line in the east (the 1919 Curzon Line was a proposed border between Poland and the Soviet Union) and the Oder/Neisse rivers in the west as frontiers, together with part of East Prussia. Stalin agreed when Churchill awarded the northern half of East Prussia to the Soviet Union. As a coda Stalin reassured Roosevelt and Churchill that the Red Army would enter the war against Japan after the conclusion of the war in Europe. Thus, in 4 days the Tehran Conference forever shaped the future of Europe and the Asia Pacific.

“Big Three” Tehran Conference Shapes Europe’s Future

|

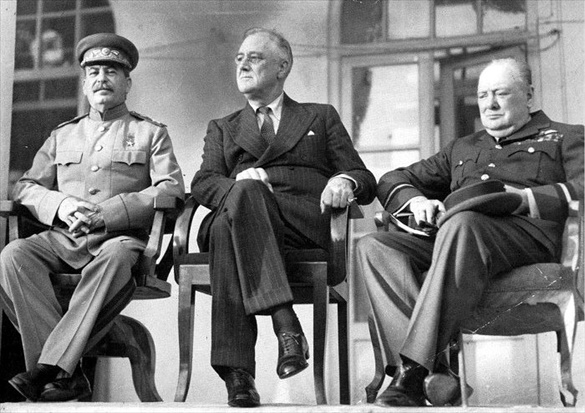

Above: The “Big Three” (left to right): Soviet Premier Marshal Joseph Stalin, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill on the portico of the Soviet embassy during the Tehran Conference (November 28 to December 1, 1943) to discuss the European Theater of war in 1943. Churchill is shown in the uniform of a Royal Air Force air commodore. Military issues dominated the talks. The Tehran Conference was the most important of the Allies’ top-level wartime meetings, including Yalta (January 30 to February 3, 1945) and Potsdam (July 17 to August 2, 1945), the latter meeting taking place after Victory in Europe Day (VE-Day, May 8, 1945) but before Victory over Japan Day (VJ-Day, August 15, 1945). The Allied leaders and their military and political staffs discussed the course of the war and its political consequences, which assumed increasing importance as the prospect of victory over Germany and its allies began to seem more likely. Stalin at last got a commitment from his Anglo-American allies to mount a major invasion of German-occupied France in mid-May 1944. When it actually happened in June 1944, the cross-channel assault relieved considerable pressure on the Red Army at a time when the Wehrmacht (German armed forces) was being hammered by Soviet military and partisan assets practically everywhere on the Eastern Front (Operation Bagration).

|  |

Left: At the Soviet embassy in Tehran on November 29, 1943, Churchill’s delegation watched the prime minister, in the name of King George VI, present the Sword of Stalingrad to the city’s namesake. Churchill is visible to the left of the raised sword. The ornate silver, gold, and crystal ceremonial sword represented a tribute to “the steel-hearted people of Stalingrad” and the climatic victory there over the Axis armies, one of war’s turning points in 1943. Churchill enjoyed a little word play with the phrase “steel-hearted people of Stalingrad,” for “Stalin,” the name adopted by the Soviet leader and the name he gave to the resilient city on the Volga River, means “man of steel” in English.

![]()

Right: After the successful conclusion of the Tehran Conference, Roosevelt, Churchill, and their staffs strategized a second time in the Egyptian capital (December 2–7, 1943). On an excursion to the Sphinx, Roosevelt asked Churchill if Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, who had commanded the Allied forces that had expelled the Axis armies from North Africa (Operation Torch) and Sicily (Operation Husky), would be acceptable to him as Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force in Europe. Churchill said it was Roosevelt’s decision but that the British would gladly support Eisenhower. Saying goodbye to the prime minister, Roosevelt flew to Tunis, North Africa. There he met Eisenhower. After the 2 men had climbed into a staff car, Roosevelt turned to the general and said, “Well, Ike, you are going to command Overlord.”

Contemporary British Newsreel Reporting on the Tehran Conference

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click