SURPRISE BODENPLATTE MAULS ALLIED AIR FORCES

SHAEP HQ, Versailles, France • January 1, 1945

Nazi Germany’s position on the Western Front had declined precipitously after the D-Day landings of Allied troops on June 6, 1944. Gen. George S. Patton’s Third U.S. Army was driving rapidly into the enemy’s rear. The German High Command (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht) was aware that German troops were in danger of being cut off and surrounded in the so-called Falaise Pocket south of Caen in Normandy. The OKW therefore issued orders to Field Marshal Gert von Rundstedt (successor to Field Marshal Guenther von Kluge, a suicide 4 months before on August 19) to withdraw his forces from France and Belgium and regroup behind the safety of the so-called Siegfried Line (Westwall) on German soil. Almost without resistance, Anglo-American troops occupied France and Belgium in October 1944.On September 16, 1944, Adolf Hitler instructed Col. Gen. Alfred Jodl and his staff at the OKW to plan a surprise offensive in the Ardennes, a heavily forested area shared by Belgium, France, and Luxembourg. On October 12, Jodl produced the first plan, Wacht am Rhein, or Watch on the Rhine. Its aim was to encircle and destroy the American armies under Gen. Omar Bradley and the Twenty-First Army Group under newly minted British Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery; capture Antwerp, the Belgian deep-water harbor that was the chief source of supply for the Anglo-American armies; and negotiate a peace treaty on the Western Front in Germany’s favor. (By now Hitler despaired of ever negotiating an armistice or peace treaty with the Soviets on the Eastern Front, so he pinned all his hopes on achieving a stalemate in the West.)

The German ground offensive, begun in foul weather on December 16, 1944, and popularly known in the West as “The Battle of the Bulge,” had a subordinate air component known as Operation Bodenplatte (Baseplate) (Unternehmen Bodenplatte). The main thrust of Bodenplatte, however, was repeatedly delayed due to bad flying weather until New Year’s Day 1945, the first day of improved weather conditions. In all, the Luftwaffe, short of experienced pilots, aircraft, and fuel, managed to deploy close to 1,000 fighters and fighter-bombers—including some Me 262s jets—in attacks on 17 British and American airfields in Belgium, the south of the Netherlands, and Eastern France.

Despite some surprise and tactical successes Bodenplatte failed to achieve German air superiority, even temporarily, while German ground forces under Supreme Commander of Army Group West Field Marshal Walter Model (another suicide down the road) continued to be exposed to punishing Allied air attacks. By January 28, 1945, the bone-tired retreating Germans had their backs to the West Wall, almost from whence they had started the month before. The Luftwaffe’s Bodenplatte campaign was the last large-scale strategic offensive operation mounted by Hermann Goering’s air force and, like the exaggerated expectations of the land-based Watch on the Rhine, was an ignominious German defeat at great expense and disproportionate loss.

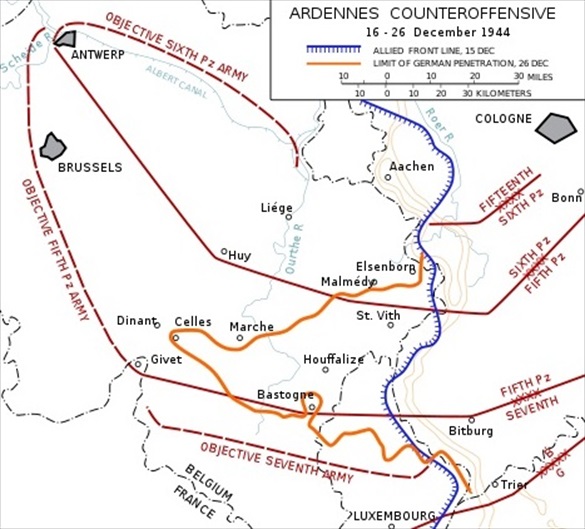

German Ardennes Ground and Air Offensives, December 1944 to January 1945

|

Above: The original objectives of the German Ardennes Offensive (Battle of the Bulge) are outlined in dashed lines on this map. The solid line indicates the Germans’ furthest advance—the 60‑mile/97‑km-wide “bulge” made in the Western Allies’ front lines. Germany’s initial 13‑division assault force consisted of 200,000 men, 340 tanks, and 280 other tracked vehicles. Reinforcements added another 100,000 men, 440 or more tanks, and 440 or more other tracked vehicles. The Luftwaffe had roughly 2,400 aircraft. Between 67,200 and 100,000 Germans were killed, wounded, or went missing between December 16, 1944, and January 25, 1945. The Americans initially had 83,000 men, 242 medium tanks, 182 other tracked vehicles across 5 divisions, 4 infantry and 1 armored. By Christmas Eve, reinforcements had brought U.S. strength up to 610,000 men. The Allies had 4,155 artillery pieces, 1,616 medium tanks, and 6,000 aircraft.

|  |

Left: Several among the 20 or so P-47 Thunderbolts at Metz-Frescaty airfield in France destroyed during Operation Bodenplatte, a subordinate operation to Operation Watch on the Rhine. The Luftwaffe managed to put 500 aircraft into the air on December 16. This first day had been the originally planned date for the strike against Allied airfields. However, the weather proved particularly bad and operations were suspended, resuming furiously on January 1, 1945, using practically every German fighter and fighter-bomber—almost 1,000 aircraft—that could still fly. The Luftwaffe bombed 11 vulnerable airfields in Belgium, 5 in Holland, and 1 in France—airfields where many of the German pilots had been formerly based. Bodenplatte cost the Luftwaffe 271 destroyed and 65 damaged aircraft, 143 pilots killed or missing, 21 wounded, and 70 taken captive. One German fighter wing (JG 4) lost 42 percent of its pilots: 18 killed, 1 wounded, and 5 taken prisoner. Many of those lost were valuable formation leaders. Incredibly, many pilots on their return flight were brought down by German flak batteries, which had not been alerted to the operation on security grounds. The Allies lost 150 combat aircraft destroyed and 111 damaged, as well as 17 noncombat aircraft, including Field Marshal Montgomery’s personal airplane. Pilot losses were few, but over 100 ground crew were killed.

![]()

Right: Fire crews at Melsbroek airfield near Brussels, Belgium, spray foam on an RAF Avro Lancaster in an attempt to save it from burning. The four-engine bomber had landed at Melsbroek with the starboard inner engine out of action and the propeller feathered.

|  |

Left: The Luftwaffe strike at Melsbroek was an outstanding success, causing considerable damage to RAF and U.S. aircraft based there. Some 15 to 20 U.S. bombers were destroyed. Among the many RAF losses were 2 entire squadrons of reconnaissance aircraft, 11 or 13 Vickers Wellington twin-engine medium bombers, 5 Spitfires, and 1 Douglas Dakota.

![]()

Right: One eyewitness said that “all hell seemed to break loose” when dozens of enemy aircraft (about 75 in all) flew over the treetops that lined Eindhoven field in the Netherlands beginning about 9:15 a.m. on January 1, 1945. For the next 20 minutes “Focke Wulfs and Messerschmitts” (Fw 190s and Bf 109s) carried out “one of the finest strafing jobs one would want to see.” The enemy pilots “systematically climbed, dived, fired their guns and even took time off to wave to some of the boys.” Before long the whole airfield was covered by heavy clouds of billowing smoke; explosions went off in every direction and fires were seen wherever one looked. Among the aircraft carnage were 8 RAF Hawker Typhoons fighter bombers and 3 RAF P‑51 Mustang fighters.

Operation Bodenplatte, January 1, 1945: Luftwaffe’s Failed Gamble to Break Allied Air Superiority Over Western Europe

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click