SOVIETS TRAP GERMANS IN HUNGARY’S CAPITAL

Budapest, Hungary • January 4, 1945

In March 1944 Adolf Hitler ordered the Wehrmacht (German armed forces) to occupy his wavering Axis ally Hungary, whose oil reserves and fuel storage tanks at Nagykanizsa (German, Grosskirchen) southwest of the capital Budapest in the Lake Balaton (German, Plattensee) area had grown strategically more important to the German war machine—this following punishing Allied air attacks on the Romanian oil refining center at Ploesti (Ploiești) in 1943 and 1944.

On this date, January 4, 1945, German troops drawn from the Eastern Front on Christmas Day 1944 failed to break the Red Army’s siege of Budapest begun 6 days earlier, on December 29, 1944, the day the provisional Hungarian leadership declared war on Germany. Hungarian resistance fighters added pressure to Hitler’s struggle to avoid losing his ally to the Soviets.

German troops, finding their retreat north across the River Danube blocked as the last bridges were blown up, managed to hold out until mid-February 1945, when fighting ended with the capture of 35,000 German soldiers, as well as 37,000 Hungarian supporters. Days earlier more than 15,000 Germans were killed trying to escape the capital. In the meantime representatives of a provisional Hungarian government signed an armistice in Moscow, one of the stepping stones to landing Hungary under a communist dictatorship in the postwar years.

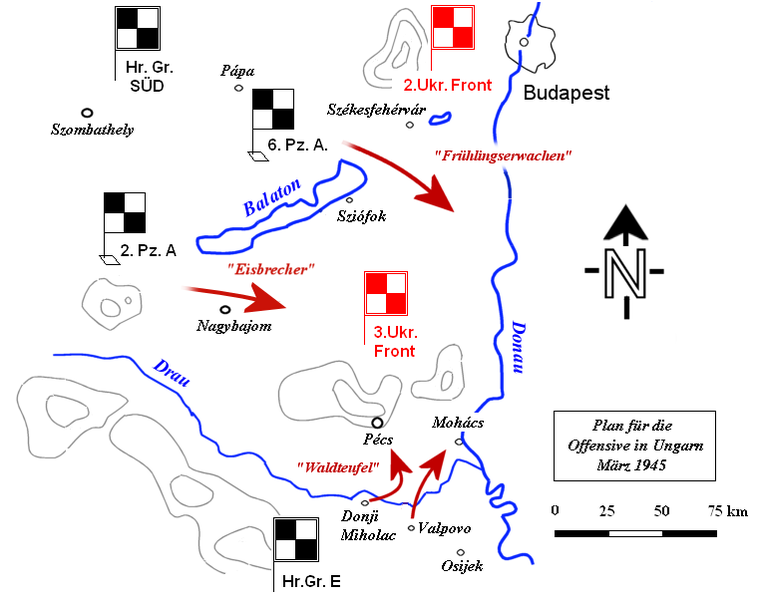

Early iin March the Germans launched their last major offensives of the war, Plattenseeoffensive, a series of 3 offensives aimed at the destruction of the Red Army in Hungary before it could reach Austria, the Reich’s southern flank. The offensives took the Red Army by surprise and made an impressive advance at this late date in the war. On March 19 Soviet ground and air forces, supported by 6 Bulgarian divisions and a corps of Tito (Yugoslavian) partisans, took all of 24 hours to recapture the territory lost during the 13 day Axis offensive. SS-Obergruppenfuehrer (Gen.) Joseph “Sepp” Dietrich, commander of the Sixth Panzer Army tasked with defending the last sources of petroleum controlled by the Germans (Operation Spring Awakening, part of Plattenseeoffensive), joked that “6th Panzer Army is well named—we have just 6 tanks left.”

On April 2, 1945, Nagykanizsa, the invaluable center of the Hungarian oil industry, fell into Soviet hands. (In early 1945, Hungarian and, to a lesser extent, Austrian oilfields supplied 80 percent of the oil used by the Wehrmacht.) Nagykanizsa’s loss left Hitler few alternatives but to rely on synthetic oil production in Germany, whose facilities lay vulnerable and largely prostrate to wave after wave of U.S. and RAF bombers from airfields in Britain and liberated Europe. As it turned out, the Plattenseeoffensive had delayed the Red Army’s drive on Austria, the scene of Hitler’s first conquest in 1938, by a mere 2 weeks.

Hungary, 1944–1945: Hitler’s Endgame on the Southeastern Front

|

Above: Map of Germany’s planned 3-part offensive in Hungary in March 1945 (Plattenseeoffensive). (Pz. A. = Panzer Army; Hr. Gr. = Heeresgruppe, or Army Group.) The largest of the 3 offensives was Unternehmen Fruehlingserwachen (Operation Spring Awakening) around Lake Balaton. The objective of Dietrich’s Sixth Panzer Army was to forestall a Soviet takeover of the oilfields in the area and perhaps even retake Budapest. The unsuccessful German offensive lasted from March 6 to the beginning of the Soviet-led counteroffensive (Balaton Defensive Operation) on March 16, 1945, which pushed Axis forces back to their starting point. The Germans and their Hungarian allies suffered upward of 47,000 dead (though probably half that figure is more accurate), the Soviets and their allies over 33,000 dead, wounded, or missing. Civilian deaths were put at 38,000.

|  |

Left: Hungarian soldiers are shown manning an antitank gun in a Budapest suburb, protecting it against a Soviet attack, November 1944.![]()

Right: The Battle (or Siege) of Budapest (December 29, 1944, to February 13, 1945) was characterized by urban warfare similar to that which the combatants had experienced in the protracted Battle of Stalingrad (August 23, 1942, to February 2, 1943) and would relive weeks later in the Battle of Berlin (April 16 to May 2, 1945). The Red Army was able to take advantage of Budapest’s urban terrain (hilly in Buda and flat in Pest) by relying heavily on snipers and sappers to advance. Fighting broke out in the sewers, as both sides used them for troop movements. Disease, food shortages, and extreme cold, ice, and snow adversely affected German and Hungarian troops. Glider flights and parachute drops helped for a time to bring supplies to the defending forces.

|  |

Left: On the night of February 11, 1945, some 28,000 German and Hungarian troops began to stream northwestwards away from their last stronghold on Buda’s Castle Hill. Soviet artillery and rocket batteries bracketed their escape route. The majority of the escapees were killed, wounded, or captured by the Soviet troops. The remaining defenders finally surrendered to the Soviets on February 13, 1945. German and Hungarian military losses were high with entire divisions wiped out. Between 99,000 and 150,000 German and Hungarian soldiers were killed, wounded, or captured. Soviet forces suffered 100,000–160,000 casualties. More than 500,000 Hungarians were transported to the Soviet Union, to labor and POW camps, including between 100,000 and 170,000 Hungarian ethnic Germans.![]()

Right: The Soviet siege of the Hungarian capital depleted the German war machine. For the Soviet troops, the siege was a final rehearsal before the Battle of Berlin. It also allowed the Soviets to breach Austria’s borders on March 30, 1945, during their Vienna Offensive. On April 13, exactly 2 months after Budapest’s surrender, the Austrian capital fell. Within 3 weeks, the Red Army was able to fly its flag from atop the Brandenburg Gate in the heart of Nazism, Berlin.

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click