SOVIETS MOVE TO TRAP GERMAN SIXTH ARMY

Stalingrad, Soviet Union • November 19, 1942

On this date in 1942 the Soviets kicked off Operation Uranus, Phase I of the Red Army’s encirclement of Gen. Friedrich Paulus’ Sixth Army (the single-largest German troop formation), as well as the German Fourth Panzer Army and the Third and Fourth Romanian armies at Stalingrad (today’s Volgograd). The Soviet high command had waited for the arrival of subzero temperatures (‑22°F/‑30°C) to harden the ground for their rolling armor and for the November landings of their Western Allies in North Africa (Operation Torch) to tie down German reserves on a second front before beginning their offensive on Germany’s Eastern Front.

The Soviets had over one million servicemen, more than 13,000 guns, nearly 900 tanks, and 1,400 aircraft to throw against the worn-out, dispirited Germans and their understrength and poorly equipped Axis cohorts. Under the leadership of Col. Gen. Aleksandr Vasilevsky and Gen. Georgy Zhukov, Red Army soldiers closed their double-pincer trap 4 days later. In January 1943 the Soviets began systematically destroying the trapped Axis forces. At month’s end Paulus capitulated. German loses in the Stalingrad pocket amounted to 20 divisions and over 150,000 men (some estimates are as high as 201,000 men), 24 generals, and 1 newly minted field marshal (Paulus himself). Losses and casualties among the Romanian, Italian, and Hungarian forces on Paulus’ flanks were even greater. Romanian losses approached 158,000 out of an initial 228,000. Italian losses were 114,520 out of the original 235,000 soldiers. Hungarian losses were 143,000 out of an initial 200,000. Losses among Soviet POW turncoats (Hiwis, or Hilfswillige as the Germans called them) range between 19,300 and 50,000. Soviet losses were 155,000 killed or missing and 331,000 wounded, though some official Russian military historians put the number of Soviet casualties at 1.1 million.

For 3 days straight German radio stations played nothing but somber music. Soldiers who had paraded 40 months earlier in triumph through Warsaw’s streets were now either dead or stumbling—disheveled, hungry, some wounded, many frostbitten—into an uncertain fate in Soviet captivity. (Less than 6,000 returned home from their ordeal as Soviet POWs.) Allied nations rejoiced with the Soviets, given the enormity and obvious strategic implications of the overwhelming Axis defeat. Indeed, the requiem for Hitler’s Third Reich was heard loudly even in Berlin, drowning out Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels’ Sportpalast speech to 14,000 carefully selected Berliners. Stalingrad had opened the eyes of the nation “to the true nature of war,” he said on February 18, 1943. Germany’s future hung in the balance in the east, and “total war is the demand of the hour.” Happily for the Allies, time was not on Germany’s side.

Axis Defeat at Stalingrad and German Declaration of “Total War”

|  |

Left: Prisoners of war Field Marshal Friedrich Paulus and two staff members meet at the headquarters of Soviet 64th Army Chief, Lt. Gen. Vasily Chuikov, January 31, 1943. Ironically, Chuikov was in Berlin in April and May 1945, where he was the first Allied officer to hear of Adolf Hitler’s April 30 suicide. He accepted the surrender of Berlin’s garrison from Gen. Helmuth Weidling on May 2.

![]()

Right: German troops as prisoners of war, early 1943. In the background is the heavily fought-over Stalingrad grain elevator. Out of the nearly 110,000 German prisoners captured in Stalingrad, only about 6,000 ever returned home. Already weakened by disease, starvation and lack of medical care during the encirclement, they were sent on brutal marches (75,000 survivors died within 3 months of capture) to prisoner camps and later to labor camps all over the Soviet Union. Some 35,000 were eventually sent on transports, of which 17,000 did not survive. Most died of wounds, disease (particularly typhus), cold, overwork, mistreatment, and malnutrition.

|  |

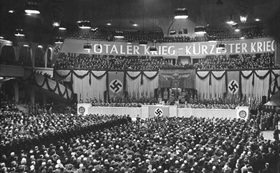

Left: As the tide of war seemed to turn against Germany and its Axis allies following Stalingrad, Joseph Goebbels felt compelled to steel the German people for coming hardships. At a rally on February 18, 1943, at the Berlin Sportpalast, the nattily attired propaganda minister addressed a large, carefully selected audience of Nazi true believers, among them Nazi Party representatives, soldiers (some wounded), doctors and nurses, scientists, teachers, and blue-collar munitions workers. Some, like Brunhilde Pomsel who served as a secretary for Goebbels from 1942 to 1945, had been ordered to the sports stadium on short notice and interspersed among the crowd to applaud in all the right places. Overhead and behind the diminutive (5‑foot‑5/165 cm) Goebbels stretched a gigantic banner in block letters: “Totaler Krieg—Kürzester Krieg” (“Total War—Shortest War”). Goebbels asked his audience, including those listening by national radio, “Do you want total war? If necessary, do you want a war more total and radical than anything that we can even imagine today?” The crowd shouted its assent. “Are you determined to follow the Fuehrer through thick and thin to victory and are you willing to accept the heaviest personal burdens?” The crowd roared, “Fuehrer command, we follow!” After the speech, Goebbels told Minister of Armaments and War Production Albert Speer that it was the best-trained audience one could have found in Germany.

![]()

Right: This 1910 postcard depicts the newly opened Sportpalast in the Berlin suburb of Schoeneberg. During the 1930s and 1940s, the Nazis used the vast indoor arena as their political grandstand—“unsere Tribuene” as Goebbels called it—preventing its use for practically anything else. Hitler spoke there on the ninth anniversary of his coming to power (January 30, 1933), and Goebbels rallied the German Volk to “Total War” (“totaler Krieg”) on February 18, 1943. On the eleventh anniversary of the Nazis’ seizing power, January 30, 1944, the Allies bombed the building. Ever-resilient Berliners used the roofless facility for an ice-skating rink the following winter. After the war the building underwent restoration, only to be razed in 1973.

Newsreel Footage of the Liberation of Stalingrad, Late January to Early February 1943

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click