SOVIETS DESTROY AXIS ARMIES AT STALINGRAD

Stalingrad, Soviet Union • January 31, 1943

On this date in 1943 Red Army staff officers arrived at German Sixth Army headquarters in Stalingrad (present-day Volgograd) to discuss surrender terms for an invading enemy now bereft of ammunition, food, effective command, and 150,000 men who belonged to the dead or missing. Field Marshal Friedrich Paulus’ defensive perimeter had shrunk to 300 yards/256 meters when he surrendered his army, despite being ordered by Adolf Hitler to fight to the last man. When told of the army’s surrender, Hitler cried, “Paulus did an about-face on the threshold of immortality. The man should have shot himself just as the old commanders threw themselves on their swords.”

The Soviet liquidation of the German Sixth Army and its Axis auxiliaries in this now devastated city on the mighty Volga River, widely celebrated in Allied media, prompted 3 days of national mourning and the closure of all nonessential businesses in Germany. It also inflicted lasting trauma on the German people, now turned sullen, depressed, and anxious for their nation’s future and for their own individual fate. Long term, the Battle of Stalingrad was a turning point in World War II. Hitler would reach no farther into the Soviet Union, and the Soviet Army acquired a new sense of its burgeoning power. The boost to Soviet morale was immeasurable, giving the Red Army impetus 6 months later to resist Germany’s armed forces at the Battle of Kursk (almost 50 German divisions containing 900,000 troops, 10,000 artillery pieces, 2,700 tanks, and 1,860 aircraft) in the most brutal armored battle in history (see photo essay below). For the third time in as many years, the mighty German Wehrmacht was stopped on the road to Moscow, the Soviet capital. The unsuccessful German assault on the bulge in Soviet lines around the city of Kursk in July 1943 marked the decisive end of Germany’s offensive capability on the Eastern Front and cleared the way for the great Soviet offensives of 1944–1945, culminating in the capture of the German capital, Berlin, in May 1945.

As for Paulus and his Sixth Army, some 91,000 survivors at Stalingrad began a forced march to POW camps in Siberia. Half died on the way, and nearly as many in the camps, where the men were designated “war criminals.” Only about 6,000, including Paulus, returned home. During his Soviet captivity the former field marshal became a vocal critic of the Nazi regime and was a witness for the prosecution at the postwar Nuremberg Trials (1945–1946). Upon his repatriation in 1953 Paulus settled in the Soviet sector of Germany (German Democratic Republic), where he died at age 66.

After Stalingrad: Battle of Kursk, July 5–16, 1943, Rings Death Bell for Hitler’s Third Reich

|

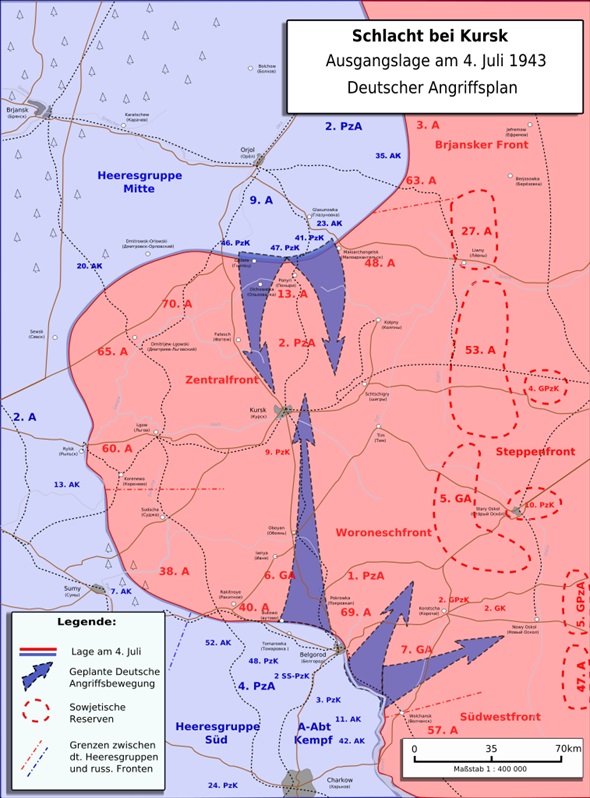

Above: Kursk salient (bulge) front lines and the German plan (Unternehmen Zitadelle; English, Operation Citadel) to eliminate the salient, thus increasing the operational density of German lines, July 4–17, 1943. The Russian city of Kursk, 280 miles/450 km southwest of Moscow, lies immediately to the left of the blue up and down arrows (Zentralfront on the map). The bulge sucked in huge numbers of opposing tanks and men, making it the arena for the greatest armored battle of World War II.

|  |

Left: German Mark VI Tiger IIIs and IVs on the move near Belgorod directly to the south and outside the Kursk salient, June 21, 1943. Their aim: penetrate and eliminate the Kursk salient.

![]()

Right: German tanks of the “Grossdeutschland Division” take up positions in the Kursk salient in early July 1943. The Grossdeutschland was considered to be the premier unit of the German Army, receiving equipment before almost all other units. The new Mark V Panthers model D that the division received on the eve of the Battle of Kursk were plagued by technical problems, suffering from engine fires and mechanical breakdowns, with many becoming disabled before reaching the battlefield.

|  |

Left: Soviet armor advances to engage the enemy. The combined Voronezh and Steppe Fronts (Woroneshfront and Steppenfront on the map) deployed about 2,418 tanks and 1,144,000 men.

![]()

Right: A Waffen-SS Mark VI Tiger I tank scores a direct hit on a Soviet T‑34 medium tank during the Battle of Kursk, July 10, 1943. The high-velocity 88 mm gun the Tiger I mounted and the quality of its advanced optical sights allowed it to devastate targets at long range with great accuracy. Reportedly it could place 5 rounds within 18‑inches/46‑centimeters of each other at 1,200 yards/1,097 meters.

|  |

Left: Soviet IL-2 combat aircraft attack an enemy formation in the southern (Voronezh) sector of the Kursk salient, July 1943.

![]()

Right: Soviet antitank riflemen take aim at an enemy tank after the Battle of Kursk had wound down, July 20, 1943. The Battle of Kursk was the first battle in which a Blitzkrieg offensive had been defeated before it could break through enemy defenses and into its strategic depths. Indeed, the Wehrmacht had barely dented the Kursk salient when Hitler reluctantly aborted Operation Citadel on July 13 following reports that the Western Allies had invaded Italy. The Battle of Kursk, it can be said, was the Soviets’ critical contribution to winning the war against the Axis.

The Battle of Kursk, July 1943

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click