SOVIET REINFORCEMENTS BOLSTER MOSCOW’S DEFENSES

Moscow, Soviet Union • October 19, 1941

On this date in 1941, the day the official “state of siege” was declared in the Soviet capital of Moscow, Red Army forces from the Soviet Far East and Siberia began arriving on the Russian Front. Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin was convinced that evacuating most of his troops from the Soviet-Japanese border on the Chinese mainland represented little risk owing, first, to a 5‑year neutrality, or nonaggression, pact the 2 countries had concluded 6 months earlier and, secondly and more importantly for its effect on reversing German fortunes in the winter of 1941, to information from a Tokyo-based spy, Richard Sorge.

The Russian-born Sorge, whose cover was that of a Nazi reporter for the German newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine among others, was the Soviet informant who had correctly predicted the date of Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union four months earlier (Operation Barbarossa) and the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. To his everlasting discredit, Stalin stubbornly refused to believe warnings from Sorge, whom the Soviet leader intensely disliked and belittled, and from other sources, including British, U.S., and Swedish diplomatic sources as well as his own military, foretelling the approximate date of Adolf Hitler’s attack on the Soviet Union. In part Stalin believed the warnings to be a ploy by agents provocateurs to disrupt the German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact of August 1939, or Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact named after the countries’ foreign ministers, which pact, wishful thinking on Stalin’s part, redirected Hitler’s aggressive instincts toward the Western democracies instead of his own totalitarian state. (Incredibly a report landed on Stalin’s desk as early as December 29, 1940—this from none other than the Soviet ambassador in Berlin who credited a Soviet agent in the German foreign office with ferreting out Fuehrer Directive No. 21, Hitler’s Barbarossa Directive 11 days earlier—that the Wehrmacht (German armed forces) had been ordered to prepare for war with the Soviet Union.)

Codenamed “Ramsay,” Richard Sorge (1895–1944) was one of the best Soviet intelligence officers of World War II, and he continued to feed Moscow information from his base in Tokyo, where the hard-drinking newspaperman had entrées in Japanese and German diplomatic circles, until arrested on October 18, 1941, by Japan’s Tokko, the country’s so-called Thought Police. (This secret police force, which was responsible for tracking down spies and subversives, is often confused with the 10,000‑man imperial security police force, or Kempeitai, equivalent to the German Gestapo.) Until his confession under torture, Sorge was assumed by the Japanese to be a German spy. (The Soviets did not officially acknowledge Sorge was on their payroll until 1964.) Sorge was hanged on November 7, 1944, along with his Japanese accomplice and fellow Communist, Hotsumi Ozaki, an advisor to Japan’s prime minister, in Sugamo Prison outside Tokyo. After the war Sugamo Prison was the execution site of 7 Japanese war criminals sentenced to death by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, among them Gen. Hideki Tōjō, Japan’s prime minister during most of World War II (1941–1944).

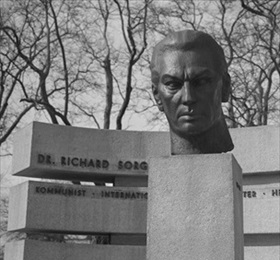

Sorge’s seminal role in the Battle of Moscow (October 2, 1941, to January 7, 1942) and perhaps in the Battle of Stalingrad (September 1942 to February 1943), during which the Germans suffered strategic defeats on their Eastern Front, is today memorialized in a Moscow park. Only after Stalin’s death in 1953 and 2 decades after Sorge’s execution did the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet (the highest executive body of the land) move to confer the nation’s highest decoration on its master spy: the Gold Star of a Hero of the Soviet Union. Several years later, in 1970, the former Soviet satellite in Eastern Germany, the German Democratic Republic, established a memorial garden named for Sorge in Dresden’s Altstadt (Old City).

Spymaster Richard Sorge: Soviet Eyes and Ears in Prewar Japan

|  |

Left: Family photograph of Richard Sorge from 1940. Sorge was born in 1895 near Baku, Azerbaijan (then part of Russia), to a German mining engineer and a Russian mother. Back in Berlin where he grew up, Sorge served in the German Army during World War I, was severely wounded (walked with a pronounced limp and was missing three fingers on his left hand), earned a PhD in political science, and joined the German Communist Party in 1919. His political views led him to leave Germany for the Soviet Union, where he became a junior agent in Moscow for the Comintern, an international communist organization. In 1929 Sorge was recruited by the head of Soviet military intelligence (GRU) and worked for that department for the rest of his life. In May 1933 the department asked Sorge to organize a spy network in Japan, the same year Sorge “joined” the Nazi Party. Sorge recruited fellow journalist and China-expert Hotsumi Ozaki, whom Japanese Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe invited to join a think tank, thereby allowing Ozame to learn about and influence important policy decisions.

![]()

Right: A memorial in a Moscow park reminds visitors of Sorge’s contributions as a Soviet intelligence operative in Japan and China (Shanghai), where he collected information about Japanese and German plans in the lead-up to World War II. Many streets in Russia are named after Sorge. British spy and James Bond author Ian Fleming called Sorge “the man whom I regard as the most formidable spy in history.” Tom Clancy, American author of numerous spy novels, called Sorge “the best spy of all time.” And best-selling spy novelist John Le Carré, who worked for MI5 and MI6, Britain’s Security Service and Secret Intelligence Service, respectively, called Sorge “the spy to end spies.”

|  |

Above: In 1970 the Communist government of East Germany accorded the half-German, half-Russian anti-fascist hero with an impressive memorial garden in Dresden. First in the list of attributions under Sorge’s name (right photo) is the word “Kommunist.” Neither the memorial garden nor the adjacent street named after him exists any longer after German reunification in 1990.

Battle of Moscow, October 1941 to January 1942, Germany’s First Defeat (You may want to mute the sound)

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click