SOVIET ARMY AND WINTER LIFT GERMAN SIEGE OF MOSCOW

Moscow, Soviet Union • December 6, 1941

Three weeks after launching Operation Barbarossa on June 22, 1941 with the express goal of “crush[ing] Soviet Russia in a quick campaign” (Fuehrer Directive 21, December 18, 1940), the Germans and their Axis partners had indeed reached close enough to Moscow to fly sorties and bomb the Soviet capital. Tactically, the Wehrmacht (German armed forces) won resounding victories, overrunning both Soviet frontier and rear defenses, slaughtering poorly equipped, poorly trained and led Red Army soldiers where they stood, destroying the Red Air Force on the ground (1,500 or more aircraft on the first day), engulfing the Soviet-occupied Baltic states, and taking over 3 million Red Army prisoners, many of them deserters, in 1941. The German juggernaut seized some of the most important economic resources of the Soviet Union, among them the heavily populated and rich agricultural heartland of the Ukraine. But Germany’s Eastern Front sucked the Wehrmacht and its Axis allies in and refused to spit them out until they’d been mauled by Mother Nature, or been bloodied in fierce combat, or been victims of both actions. By November 1 the advancing German Army and Luftwaffe were paralyzed in their tracks by the worst winter weather in 140 years. The Wehrmacht in 1941 was simply not equipped for this kind of winter warfare; the Red Army was.

On this date, December 6, 1941, outside Moscow, Soviet forces attacked Axis lines to begin their successful offensive on their western front, the Battle of Moscow (German, Operation Typhoon). Elements of 2nd Panzer Division, reinforcing Gen. Ludwig Bock’s Army Group Center in its push toward Moscow, got within 6 miles/9.6 km of the capital and could see the gold domes of the city’s churches, but the Wehrmacht got no further in a white Russian hell where exhausted and ill-clad soldiers died from severe frostbite; fuel (of which there was little), motors, and transmissions froze; and machine guns ceased firing. (The day before the temperature stood at 36 below zero.) Gen. Bock and Gen. Heinz Guderian, who held command of the Second Panzer Army, knew their men were at the end of their abilities and resources. In one 3‑week period, German dead and wounded totaled 155,000. Some divisions were a fraction of their original strength. Hundreds of miles/kilometers from their main supply depots front-line German forces were now depending on air-dropped supplies to survive. Back at Fuehrer headquarters in East Prussia, Gen. Eduard Wagner, the Wehrmacht quartermaster-general, stated for the record: “We are at the end of our personnel and materiel strength.” Col. Gen. Franz Halder, Chief of the Army High Command General Staff, recorded the same in a diary entry: “We have reached the end of our strength.”

General Field Marshal Walther von Brauchitsch responded to the disaster with coronary failure and resigned his post as Commander-in-Chief (Oberbefehlshaber) of the German Army (Heer). Bock was replaced and Guderian summarily dismissed for trying to persuade Adolf Hitler to reverse his December 16 order, reaffirmed 4 days later in a strongly worded Haltebefehl (stand-fast) directive to Army Group Center, to hold the front line at all costs. Brauchitsch’s replacement as supreme army commander on December 19 was none other than Hitler himself. Hitler’s insistence on “fanatical resistance,” without regard to German casualties, could not stem the Soviet offensive, which ended on January 7, 1942, after bone-weary and depleted Axis armies had been pushed back 60 to 150 miles/96 to 241 km. For the duration of the war Hitler, whose highest rank as a German soldier in World War I was lance corporal (Gefreiter) and his military occupational specialty (MOS) that of regimental message runner, would assume operational (but not administrative) command of the army on the Eastern Front right up to the day of his suicide on April 30, 1945, as Red Army soldiers closed in on his underground headquarters beneath the shattered capital of his Thousand Year Reich.

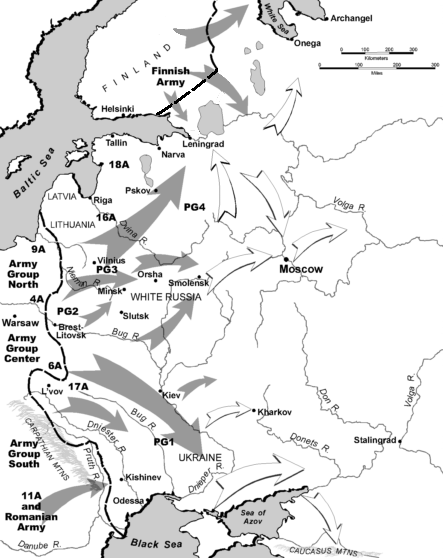

Operation Barbarossa: Germany’s Invasion of the Soviet Union, 1941

|

Above: Map of Axis and Finnish operations against the Soviet Union, June 22 to December 5, 1941. Operation Barbarossa was the largest military operation in history in both manpower and casualties. It eventually cost the German Army (Heer) over 210,000 killed and missing and 620,000 wounded in 1941, a third of whom became casualties after October 1. Unknown is the precise number of casualties among Romanian, Hungarian, and Waffen‑SS units, as well as co-belligerent Finns.

|  |

Left: Panzer units from Army Group Center speed into Western Belarus (the Soviet Republic of Byelorussia; White Russia on the map) on an unpaved road, June 1941. By the end of the first week of Operation Barbarossa, all 3 German Army Groups—North, Center, and South—had achieved major campaign objectives. The chief of the Army High Command General Staff, Franz Halder, trumpeted in his diary: “It is thus probably no overstatement to say that the Russian Campaign has been won in the space of 2 weeks.” Hitler’s Luftwaffe adjutant wrote a couple of days after Barbarossa’s kickoff: “The ease of our victories along the whole front came as a surprise to both Army and Luftwaffe.” When the Belarus capital Minsk fell on June 28, German troops, given their rate of advance, would have been in Moscow, 434 miles/698 km to the east, within 2 weeks. “Everything is lost,” Soviet leader Joseph Stalin lamented upon learning of Minsk’s loss. Determined to give lie to his earlier lamentation, Stalin had himself appointed chairman of the State Defense Committee on July 1, 1941, where he directed the successful prosecution of the war against Germany.

![]()

Right: A German tank and crouching infantry make good time crossing the steppes in July 1941. By then some German spearheads had already advanced over 250 miles/402 km from their starting positions. But 4 months into the campaign, temperatures fell and there was continual rain, which by mid-October would have turned this unpaved road into a muddy bog. The changed road conditions slowed the German advance on Moscow (Operation Typhoon) to as little as 2 miles/3.2 km a day

|  |

Left: German soldiers exhaust themselves pulling a staff car through heavy mud on a Russian road, November 1941. Hitler, arrogant and ruinously overconfident owing to his blitz of successes in Western Europe, expected a victory in the East within a few months, and therefore he did not prepare his Wehrmacht for a campaign that might last into a wet late fall, much less a bitterly cold winter. The assumption that the Soviet Union would quickly capitulate proved to be his, and Nazi Germany’s, tragic undoing.

![]()

Right: On December 2, 1941, the first blizzards of the Russian winter began just as one unit of the Wehrmacht, a panzer pioneer battalion of the 258th Infantry Division that had halted in the township of Khimki close to the Moscow ring road, reputedly caught a glimpse of the golden domes and spires of Moscow’s Red Square and the Kremlin 14 miles/22 km to the south using high-powered binoculars. (The spires of the Kremlin had been camouflaged with dark paint and the Kremlin walls were painted to look like buildings with windows, so the account appears to have been exaggerated or the Germans saw other towers and spires.) Sometime later a reconnaissance battalion is said to have crept to within 5 miles/8 km of Moscow, but that was as close to the military prize as any Wehrmacht unit managed. In this photo a Panzer IV tank in white camouflage is stranded in deep Russian snow as its winter-clad crew attempts to free it. At the right edge of the photo is a war correspondent (admittedly hard to see), who filmed the scene for audiences hungry for front-line news back in Germany.

|  |

Left: Against the backdrop of burning houses on the outskirts of Moscow in November or December 1941 German medics provide aid to a wounded comrade. Army Group Center suffered more than 300,000 casualties.

![]()

Right: Faces wrapped in scarves and wearing heavy greatcoats, 2 German soldiers in knee-deep snow stand guard duty west of Moscow, December 1941. Those lucky enough to own a toque—a sleave-like wool tube that was pulled over one’s head—were able to protect their necks and parts of their face from the bitter cold. Sometimes soldiers wore 2 or 3 toques along with scarves for extra insulation. December’s low temperature reached ‑40°F/‑40°C. More than 130,000 cases of frostbite were reported among German soldiers. The same arctic conditions plagued Soviet troops, but they were better prepared for the cold.

Battle of Moscow (Operation Typhoon), September 30 to December 8, 1941

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click