SKORZENY TO HEAD ARDENNES SABOTAGE UNIT

Wolf’s Lair HQ, East Prussia, Germany • October 21, 1944

On this date in 1944 Adolf Hitler summoned SS-Obersturmbannfuehrer (Lt. Gen.) Otto Skorzeny to Fuehrer headquarters deep in the East Prussian wilderniss near Rastenberg (present-day Kętrzyn, Poland). The scar-faced 6‑ft, 4‑in/193‑centimeter Skorzeny had made a name for himself participating in a derring-do operation that succeeded in rescuing Italian dictator Benito Mussolini from captivity high in an Apennines redoubt on September 12, 1943. At the Wolfsschanze Hilter told his fellow Austrian that his next assignment would be the most important of his life: it was to capture bridges over the Meuse River in Belguim by members of the Wehrmacht (German armed forces) masquerading as U.S. soldiers and sow confusion behind Allied lines during the upcoming Ardennes Offensive (Battle of the Bulge), eventually slated to kick off in mid‑December.

Skorzeny prepared for his mission of sabotage, codenamed Unternehmen Greif (Operation Griffin), by drawing on as many English-speaking men as possible from the Kriegsmarine, the German Army, the Waffen‑SS, and the Luftwaffe. The 2,676 mostly volunteer men of the new 150th SS Panzer Brigade, a unit of Josef “Sepp” Dietrich’s Sixth Panzer Army, were told their efforts would have a decisive effect on the war. Dozens of the recruits were outfitted in American uniforms collected from POWs (officers and enlisted men) held in German camps. At a heavily guarded military encampment in Grafenwoehr, Bavaria, the men were taught how to salute like American soldiers, took their orders in English, learned American slang by watching American movies and newsreels, polished their accents, and ate K‑rations. The usual commando skills were emphasized as well. The secret brigade-in-training did not, however, remain secret from Allied codebreakers at Bletchley Park in England, who intercepted the German High Command’s decision to set up a special volunteer force in the west whose ranks had a “knowledge of English and American idiom.” Later, a document outlining Operation Greif’s elements of deception, though not its objectives, fell into U.S. hands.

Eventually 150 men out of 600 English-speakers in Kampfgruppe (combat group) Skorzeny were formed into Einheit Stielau, the commando unit assembled from the parent 150th Panzer Brigade. The men wore U.S. Army uniforms, combat boots, and dog-tags, were armed with captured U.S. Army weapons, and drove captured Army Jeeps. Some commandos were directed to destroy bridges, ammunition dumps, fuel depots, field telephone cables and radio stations, and with issuing false orders. Others scouted routes to the Meuse River, observed enemy strength, and sowed havoc by reversing road signs, removing minefield warnings, and cordoning off roads with warnings of nonexistent mines.

On the start date of Germany’s Ardennes onslaught, December 16, 1944, the 150th Panzer Brigade followed in the spearheading tracks of 3 Panzer divisions. Within days Skorzeny’s men had changed U.S. soldiers’ behavior toward one another as troops began asking other soldiers American trivia questions in order to flush out enemy infiltrators. Even British Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery was caught in the American dragnet when soldiers shot out the tires of his staff car and detained him for several hours until a British soldier was called in to vouch for the real (fuming) Montgomery; a rumor circulated that Skorzeny had found a Montgomery double. In all, 44 German soldiers wearing U.S. uniforms were sent through U.S. lines, with the last men being sent on December 19. With Skorzeny’s “Trojan Horse trick” having been exposed and American near paranoia ebbing (though not without several tragic cases of mistaken identity), the 150th Panzer Brigade was seconded to the 1st SS Panzer Division and used as a regular panzer brigade.

German Saboteurs Spread Confusion at Start of Ardennes Offensive, December 1944

|

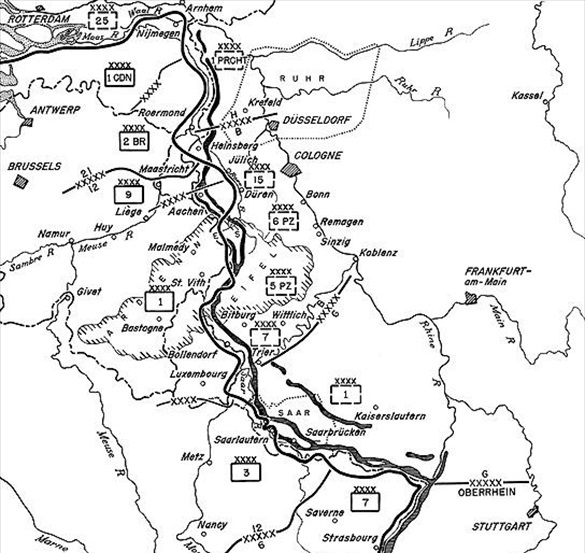

Above: The Ardennes Forest (hashed area to the east of the heavy north-south front line) on the eve of the German offensive, known in the West as the Battle of the Bulge (December 16, 1944, to January 25, 1945). The offensive was Hitler’s failed gamble to split the Western Allies and prevent their invasion of Germany’s heavily populated and industrial Ruhr district (top of map).

|  |

Left: SS-Sturmbannfuehrer (Major) Otto Skorzeny with the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross and Helmet as commander of the 300-man SS unit “Friedenthal.” Skorzeny took more than a dozen men of his unit to Italy in 1943 when he helped snatch the deposed Italian dictator Benito Mussolini from captivity. Photo from December 31, 1942. Hitler selected Skorzeny (1908–1975) to be the leader of Operation Greif. Admired by Hitler and almost worshiped by Waffen-SS men for his legendary exploits, Skorzeny was loathed by regular German Army officers as a “typical evil Nazi” who employed “typical SS methods,” an “Austrian criminal,” “a real dirty dog . . . shooting is much too good for him.” (Quoted in Antony Beevor, Ardennes 1944, pp. 91–92.) Skorzeny and 9 officers of the 150th Panzer Brigade were tried as war criminals at the postwar Dachau Trials for allegedly violating the laws of war during the Battle of the Bulge. The charge: improperly using American uniforms “by entering into combat disguised therewith and treacherously firing upon and killing members of the armed forces of the United States.” Acquitting all defendants, the U.S. military tribunal drew a distinction between using enemy uniforms during combat and for other purposes, including deception; also, it could not be shown that Skorzeny himself had given any orders to fight in U.S. uniforms.

![]()

Right: On December 19, 1944, during the Battle of the Bulge, three of Skorzeny’s Trojan horse commandos, Sgt. Manfred Pernass, Sgt. Guenther Billing, and Lance Cpl. Wilhelm Schmidt, were captured behind U.S. lines in American uniforms. The three were given a military trial 2 days later, found guilty of espionage, and executed by firing squad on December 23. Three more commandos were also tried on the same day and shot on the 26th. Seven more were tried on December 26 and executed on the 30th. The next day 3 others were tried and executed on January 13, 1945. Members of the British 29th Armoured Brigade defending bridges over the Meuse River in Belgium killed 2 Skorzeny commandos riding in an American Jeep on the night of December 23/24. Operation Greif’s leader, Guenther Schulz, was tried by a military commission in May 1945 and executed near the German city of Braunschweig on June 4, 1945.

|  |

Left: German Mark V Panther tanks aboard railway flatbeds en route to the Ardennes, late 1944.

![]()

Right: A knocked-out Mark VG Panther tank, one of a handful of German Mark IVs and Panthers assigned to the 150th Panzer Brigade and disguised to look like a U.S. M10 tank destroyer in Operation Greif. Thin steel plates were welded to this Panther’s 45–ton hull and turret, minus its cupola, to mimic the silhouette of the American tank hunter. Manned by a crew of 5, the German tanks were painted U.S. olive drab and applied with U.S. markings. However, the Panther’s distinctive interleaved wheel train remained unchanged, so that these counterfeit M10s were readily recognized by U.S. troops and destroyed. Skorzeny later strongly criticized the use of these converted Panthers, saying they could only deceive someone at night from a distance or maybe a raw recruit up close.

Einheit Stielau: English-speaking German Saboteurs in U.S. Army Uniforms and Vehicles, Battle of the Bugle, December 1944

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click