SECOND U.S. A-BOMB LEVELS NAGASAKI

509th Composite Group HQ, Tinian, Mariana Islands • August 9, 1945

Despite the shockwaves that Hiroshima’s destruction on August 6, 1945, sent through Imperial circles, Japan’s government refused to agree to an unconditional surrender; their leaders insisted on preconditions, chief among them protecting the “prerogatives” of Emperor Hirohito as Japan’s “sovereign ruler.” (Had there been no Japanese foot-dragging or had the Truman administration finessed a diplomatic approach sooner for protecting the postwar status of the emperor, would the Pacific War have been over before the first or maybe the second atomic bombing?) The Soviet declaration of war against Japan early on August 9 and a fast-moving Red Army invasion of the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo (Chinese Manchuria) and North Korea (the Soviets had redeployed an additional 170,000 troops and hundreds of tanks and guns to Manchukuo’s border on July 28) shattered any expectation that Japan’s large Kwantung Army on the Asian mainland could hold back her enemies’ conventional forces, now numbering well over 1 million men. Yet even these events failed to move Japan’s fire-breathing warlords.

After dropping millions of leaflets and after hours of radio broadcasting from American-held Saipan Island warning Japan of further devastating raids following Hiroshima’s destruction, to no avail (the 48‑hour deadline to hear back had expired), the U.S. settled on exploding a second, more powerful atomic device over Kokura (present-day Kitakyūshū) on this date, August 9, 1945. (Kokura on the southernmost Japanese island of Kyūshū was the location of a chemical weapons plant and one of the largest arsenals still standing in Japan.) Bockscar, the B‑29 carrying “Fat Man,” as the nearly 10,000 lb./5 U.S. ton plutonium‑239 bomb was nicknamed, circled Kokura 3 times but did not drop its lethal payload due to cloud cover, industrial haze perhaps, and smoke drifting east over the city after an incendiary raid by over 200 B‑29s on nearby Yahata (Yawata), “the Pittsburgh of Japan,” less than 24 hours before.

Owing to fuel constraints, Bockscar turned south and flew to its backup target, Nagasaki, a small industrial port city that existed mostly for military manufacturing, also on Kyūshū. That city was also covered by the same storm system over Kokura, but at the last minute the bombardier was able to secure the required visual contact with the target through a hole in the clouds. The bomb destroyed about 44 percent of Nagasaki, killed perhaps 35,000, and injured 60,000 out of 263,000 who were there that day. Further aerial immolation of Japanese cities was averted in part by a 9‑day U.S. propaganda campaign that included radio broadcasts and air-dropping 5–6 million leaflets that graphically described what remained of the 2 cities. The leaflets caused conditions close to panic in some cities.

By now U.S. air raids had killed 600,000 Japanese civilians. The carnage stopped at noon August 15 (Tokyo time), 1945, when Hirohito addressed his subjects by radio in courtly, Orwellian doublespeak. A lover of peace (the name of his reign, Shōwa, means “bright peace”), Hirohito said it was “far from Our thought either to infringe upon the sovereignty of other nations or to embark upon territorial aggrandizement.” Approximately 4.4 million military and 24 million civilian deaths later, the emperor had no words of apology for what he and his subjects had done to “assure Japan’s self-preservation and the stabilization of East Asia.” The words “surrender” and “defeat” never crossed his lips, which left some listeners wondering if Japan had surrendered or if the emperor was exhorting his subjects to resist the anticipated enemy invasion. But surrender Hirohito did on August 15, ending World War II and his nation’s nearly half-century of aggression, death, and destruction in Asia and the Pacific.

Nagasaki: Object of America’s Second Atomic Bomb, August 9, 1945

|  |

Left: Bockscar and crew delivered their own version of death and destruction when dropping “Fat Man” on Nagasaki on August 9, 1945. Twenty‑five-year-old Maj. Charles W. Sweeney, Bockscar’s commander, stands in the second row wearing the dark jacket. Bockscar and Enola Gay were “Silverplate” B‑29s, which were specially modified to carry atomic weapons at extreme flight distances. (For instance, tail guns and armor were removed to save weight.) They were 2 of 15 Silverplate B‑29s used by the 393nd Bombardment Squadron, 509th Composite Group, which carried out the 2 lethal bombings. Interestingly, Capt. Frederick Bock, whose last name was turned into the moniker for the B‑29 Sweeney borrowed that fateful day, piloted instead The Great Artiste, the Silverplate used to collect scientific data and photograph the effects caused by “Fat Man” exploding over its target. Bockscar can be seen today at the U.S. Air Force Museum near Dayton, Ohio, while Enola Gay is part of the National Air and Space Museum Collection’s at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia. A representation of The Great Artiste is on static display at the “Spirit Gate” of Whiteman Air Force Base, Missouri, now home base of the 509th Operations Group.

![]()

Right: The smokestacks of Nagasaki’s sprawling Mitsubishi Steel and Armament Works. The plant was located about 2,500 ft./762 m downriver from ground zero. Nagasaki’s hilly terrain tempered the bomb’s destructive effects, whereas Hiroshima was flat and open and thus suffered much greater devastation.

|  |

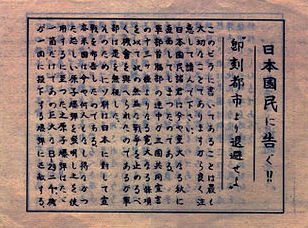

Above: Front and back of leaflets that urged the country’s quick surrender were dropped over Japan by the 509th Composite Group, a group that comprised B‑29 bombers and transport aircraft. The 509th was the United States Army Air Forces component of the Manhattan Project under the command of 30‑year-old Col. Paul Tibbets, Jr.

|  |

Left: After being assembled, “Fat Man” underwent a final procedure outside the assembly building, where exterior crevices were filled with putty and then sprayed with sealant to maintain the proper environment within the device during the time it would take to deliver it over its target. Once the sealant application had been substantially completed, workers began scrawling their names and messages (some obscene) on the tail fin assembly and body of the device (nearly impossible to see in this image), including one from Rear Adm. William R. Purnell, who wrote: “A Second Kiss for Hirohito!” Purnell, one of the “Tinian Joint Chiefs,” was the U.S. Navy representative on the Military Policy Committee, the 3‑man committee that oversaw the Manhattan Project, and was the personal representative of Adm. Earnest J. King, Commander in Chief, United States Fleet.

![]()

Right: This photo shows “Fat Man” being towed to Tinian’s North Field under military police escort. On arrival the bomb was lowered by hydraulic lift into a bomb pit. Then Bockscar backed up over the pit with bomb bay doors open and the bomb was raised into the plane’s belly. In the belly prior to takeoff the bomb was armed. Before Bockscar’s commander left on his mission to Nagasaki, Sweeney ran into Adm. Purnell, who stumped him by asking the major to guess the cost of the bomb on his aircraft. Two billion dollars, Purnell stated. (Actually, it was the entire Manhattan Project that cost $2 billion, or over $35.7 billion in 2025 dollars adjusted for inflation.) Sweeney answered the admiral’s second question correctly when he estimated Bockscar’s value at over a half-million dollars. “I’d suggest you keep those relative values in mind for this mission,” Purnell told Sweeney.

|

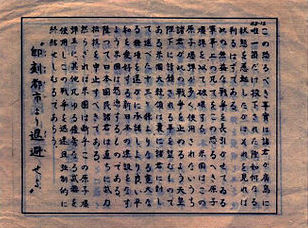

Left: At the time this photo was made, August 6, 1945, a cloud of radioactive materials billowed 20,000 ft./6,096 m above Hiroshima while it spread over 10,000 ft./3,048 m at the base of the rising column. Six planes of the 509th Composite Group participated in the Hiroshima mission: one to carry the bomb (Col. Paul Tibbet’s Enola Gay); one to take scientific measurements of the blast (The Great Artiste under the command of Maj. Charles Sweeney); and a third to take photographs (Necessary Evil). The other 3 flew approximately an hour ahead to act as weather scouts. Bad weather disqualified a target, as scientists insisted on a visual delivery. The primary target that day was Hiroshima. Secondary and tertiary targets were Kokura and Nagasaki, respectively.

![]()

Right: Radioactive Radioactive smoke and dust rose more than 60,000 ft. into the air over Nagasaki after the city was bombed by the crew of Bockscar on August 9, 1945. The U.S. had been unable to produce enough uranium to make a second atomic bomb similar to the bomb dropped on Hiroshima. Thus, for their second atomic warhead the Americans were obliged to use a plutonium core and a wholly different triggering device to detonate the bomb. “Fat Man” had a blast yield equivalent to 21,000 tons of TNT, a quarter more than the device dropped over Hiroshima. The next day, August 10, the Japanese government presented a letter of protest for the 2 atomic bombings to the U.S. government via the Swiss embassy in Washington. It was not, however, until after the war that the full measure of the atomic horror sunk in. Perhaps that’s part of the reason why, 80 years after Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the establishment of nuclear weapon arsenals by 9 nations (at last count), the planet has not witnessed a third such horror.

Air Force Story (1953), “Air War Against Japan, 1944–1945, Hiroshima and Nagasaki A-Bombs” (May want to skip first minute)

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click