SEA LION (SEELOEWE), OPERATION (1940)

| When | Preparations completed in August 1940 |

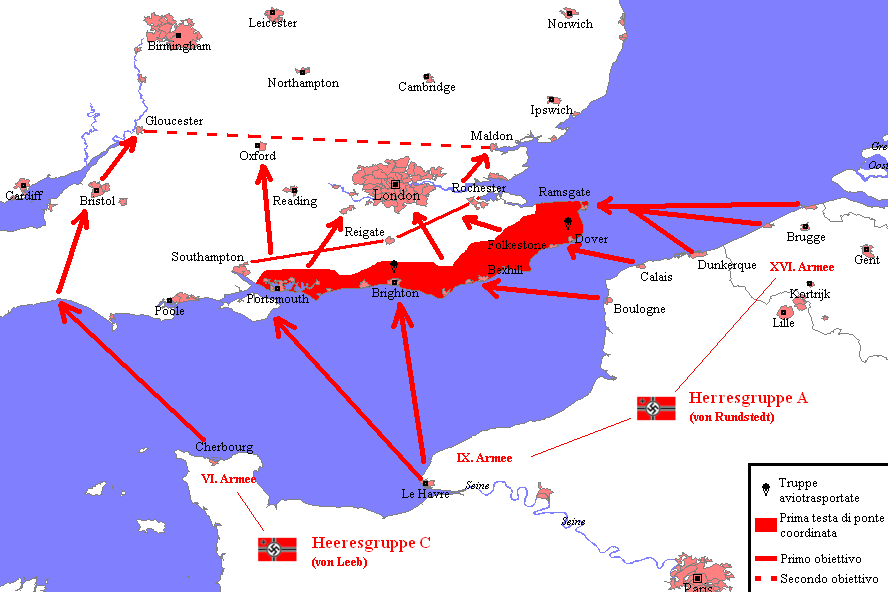

| Where | Southeast English coast from Ramsgate and Dover (county Kent) in the north to Portsmouth (county Sussex) and Devon in the south, as well as the Isle of Wight off the south coast of Hampshire

|

| Who | Staff of the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW) (English: Supreme Command of the Armed Forces), Army Group A under Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt (1875–1895), and Army Group C under Field Marshal Wilhelm von Leeb (1876–1956). Plans called for an amphibious landing with around 67,000 men in the first echelon and an airborne division to support them. |

| Why | Britain’s ally France officially surrendered to Hitler’s invading forces on June 22, 1940, in the full glare of German media in the same railroad car where Kaiser Wilhelm II’s representatives had signed the World War I surrender document 21 years before. The refusal of Britain to negotiate an end to European hostilities prompted Hitler to plan for an airborne and amphibious invasion of England to eliminate that country’s ability to interfere with German military and political hegemony in Europe. |

| What | On July 16, 1940, Hitler issued Fuehrer Directive 16, setting in motion preparations for Operation Sea Lion (Unternehmen Seeloewe). In harbors up and down France’s Pas de Calais and northward along the coast of the Low Countries the Germans began assembling an armada of barges and other transport craft for a cross-Channel invasion of England. Sea Lion called for six coordinated landings along a hundred miles of England’s south coast, backed by an airborne assault. But to have had any chance of success, the operation would have required air and naval supremacy over the English Channel. The Royal Navy alone had over a thousand warships, many of which patrolled the Channel, and behind them were squadrons of destroyers, cruisers, and battleships ready to spring into action. Col.-Gen. Alfred Jodl, Chief of Operations in the OKW; Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, commander-in-chief of the Kriegsmarine considerably weakened by naval losses during the Norwegian campaign (April–June 1940); and Air Marshal Hermann Goering expressed reservations at one time or other as to whether Germany would ever have mastery over the choppy and unpredictable English Channel or in English skies. With the Luftwaffe’s inability to deliver a knockout punch to the Royal Air Force during the Battle of Britain (June–September 1940), Sea Lion was postponed indefinitely on September 17, 1940. |

| Outcome | Had Operation Sea Lion succeeded, Britain and Ireland would have been divided into six military-economic commands. Over 2,800 people would have been arrested immediately, and the occupation authorities would begin liquidating Britain’s Jewish population, which numbered over 300,000. The able-bodied male population between the ages of 17 and 45 would for the most part be interned and dispatched to the Continent. This represented about 25% of the British population. Britain was then to be plundered for anything of financial, military, industrial, or cultural value. Following Hitler’s postponement of the invasion, a palpable sense of relief swept over the Wehrmacht. Army Group A commander Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt took this view. Sea Lion was rescheduled for some time the next year but it was not until February 13, 1942, long after Operation Barbarossa had been unleashed on the Soviet Union, that forces earmarked for the Sea Lion were released to other duties. |

![]()

Operation Sea Lion: Actually a Very Bad Idea (Ignore 11–second promotion 39 seconds into the video)

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click