SCAPA FLOW SINKING DEALS ROYAL NAVY SEVERE BLOW

Scapa Flow, Northern Coast of Scotland, Orkney Islands • October 14, 1939

Illuminated only by the northern lights (aurora borealis) early on this date in 1939, barely 6 weeks into World War II in Europe, a German Type VIIB diesel-electric submarine under the command of Kapitaenleutnant (Captain Lieutenant) Guenther Prien infiltrated the defenses of Scapa Flow, the newly reactivated main anchorage for the British Home Fleet in Scotland’s Orkney Islands. Sliding quietly on the surface of the water, Prien was struck by how few capital ships were at anchor. (The Home Fleet had recently been dispersed.) However, silhouetted against the northern lights the elderly (1916–1917) 30,450‑ton battleship HMS Royal Oak had been spotted by a lookout on the sub’s bridge. The 620‑ft/189‑m‑long battlewagon, just arrived at Scapa Flow after being battered by fierce North Atlantic storms and, considered unfit for modern combat, had been pressed into service as an antiaircraft gun platform.

Prien angled his weapon at the backlit big ship. After firing a 3-torpedo spread that caused little damage to the Royal Oak’s starboard bow (Prien believed all torpedoes had missed their target), U‑47 reluctantly turned to make its escape. At that moment Prien realized he was in no immediate danger from patrolling British vessels or land-based artillery, so he swung his submarine around for another attack. His second array of 3 torpedoes blew 3 holes amidships, in the Royal Oak’s engine room and a magazine room, where a fire soon raged out of control and hurled metal everywhere. Inside 13 minutes the venerable battleship had heeled over and slipped beneath the oil-slick surface. Of 1,234 sailors aboard, 833 were lost, including 126 “boy sailors” (sailors under 18). Undetected, U‑47 made a clean getaway, Royal Navy officials in the confusion of the moment ignorant of the agent of the Royal Oak’s destruction.

The spectacularly successful penetration of Scapa Flow was another humiliating blow to the prestige of the Royal Navy. The month before a U-boat attack had sunk the British cruiser-turned-aircraft-carrier HMS Courageous off southwest Ireland in 20 minutes flat for a loss of 519 men and 48 torpedo planes during the first U‑boat offensive against the Royal Navy. For Prien and the Kriegsmarine, the naval raid on Scapa Flow brought instant fame to the 31‑year-old skipper, who before Scapa Flow had only commanded one wartime patrol. (On that patrol Prien sank the war’s second British ship, plus two more, for a total of 8,270 tons; the first British ship sunk was the ill-fated 13,581‑ton passenger liner SS Athenia, allegedly mistaken by U‑30 for a troopship or armed merchant cruiser.) Despite U‑47’s single kill, and an antiquated one at that, the Kriegsmarine gave Prien and his dare-devil crew a hero’s welcome when the sub tied up at a Wilhelmshaven pier. A few days later at a gala luncheon for Prien and his 44‑member crew in the Reichs Chancellery in Berlin Adolf Hitler personally awarded Prien the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves, the first sailor of the U‑boat service and the second member of the Kriegsmarine to receive this award. Prien and his crewmembers had earlier in the week received the Iron Cross First and Second Class, respectively, from Grand Admiral Erich Raeder.

Sinking the HMS Royal Oak: German Naval Raid on Scapa Flow, October 14, 1939

|

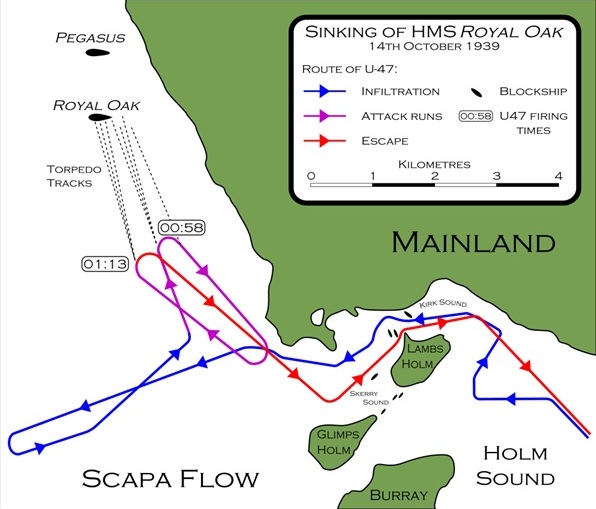

Above: Map showing the route of Guenther Prien’s 218-ft/66-m-long submarine, U-47, infiltrating the defenses of Scapa Flow and the destruction of the British battleship HMS Royal Oak, October 14, 1939. Scapa Flow controlled the entrances to the North Sea and was considered remote enough from German land-based aircraft to be a safe anchorage (though German reconnaissance aircraft had recently overflown the area). A 125‑sq-mile/324‑sq‑km natural harbor, Scapa Flow was surrounded by a ring of islands separated by a half-dozen shallow channels subject to swift flood tides and treacherous currents. Scapa Flow provided the primary anchorage for the main fleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War and was reactivated at the start of the Second World War, becoming the main base of the Home Fleet, which operated in British territorial waters. Scapa Flow’s natural and artificial defenses, while still strong, were recognized as needing improvement. In the early weeks after September 3, 1939, harbor defenses were in the process of being strengthened by installing booms and antiaircraft batteries and sinking additional blockships, or weighted hulks held on the seabed by cables anchored on land.

|  |

Left: The mighty British battleship HMS Royal Oak. First published in 1938 this image reappeared in the Liverpool Daily Post on October 16, 1939, following the loss of the Royal Oak.

![]()

Right: Lieutenant Commander Guenther Prien (1908–1941). Eight years in the German merchant marine, where he rose from lowly cabin boy to first mate, Prien volunteered at age 25 for U‑boat duty under then Fregattenkapitaen (Frigate Captain) Karl Doenitz. Prien, since December 1938 skipper of U‑47, was the first member of the Kriegsmarine to receive the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves, Germany’s highest military decoration in October 1939. Under Prien’s command U‑47 sank 30 Allied ships totaling 162,769 tons and damaged 9 more in its 10 war patrols. Prien’s boldest and most famous exploit was to sink the British battleship HMS Royal Oak at anchor in Scapa Flow, Great Britain’s chief naval base in the Orkney Islands far to the north in Scotland. For this he received the nickname “Der Stier (Bull) von Scapa Flow.” A few months after sinking the Royal Oak, Prien’s autobiography, Mein Weg Nach Scapa Flow, was published and sold a whopping 750,000 copies. U‑47 was last heard from in early March 1941, lost with all hands in waters off the west coast of Scotland.

|

Above: Guenther Prien (left) being congratulated on his successful mission by German Commander of Submarines Commodore Karl Doenitz (middle) and Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, Wilhelmshaven, October 17, 1939. Early in the outbreak of hostilities Doenitz had Scapa Flow in his crosshairs and the skilled Prien, though in command of U‑47 for less than a year, was his choice to lead the hazardous undertaking. With any luck the attack on the Home Fleet’s main anchorage would nudge the Royal Navy into withdrawing to a less favorable location (from the British perspective), which Doenitz believed would then give his boats and the Kriegsmarine’s surface raiders, consisting of brand new battleships and heavy cruisers, greater access to the resource-rich shipping lanes of the North Atlantic. There the 2 naval branches could inflict a hellish carnage on Britain’s venerable navy and its fleet of 2,000 merchant ships, the largest fleet of tankers and transports in the world. The positive propaganda value of the Scapa Flow raid (enhanced respect for the Kriegsmarine and its submarine branch; Commodore Doenitz was swiftly promoted to rear admiral in the wake of the raid) and its negative effect on British morale were not to be discounted, neither in Doenitz’s view nor that of Reich Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels.

The Sinking of HMS Royal Oak, an STV and History Channel Documentary

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click