ROOSEVELT TOLD WEST COAST JAPANESE POSE NO SECURITY RISK

Washington, D.C. • November 7, 1941

Relations between the U.S. and Japan grew chilly in mid-1941 after President Franklin D. Roosevelt froze Japanese assets in the U.S. and embargoed oil and gasoline exports to Japan in retaliation for that country’s occupation of Indochinese airfields in what is today Vietnam. The year before Roosevelt had banned exports of aviation fuel, machine tools, and scrap iron and steel in response to Japan’s military incursions in China. Would piling sanctions on top of sanctions fire up U.S.-born and immigrant Japanese living in the U.S. to a point where they could pose a danger to the internal peace and security of the country? The president set to find out.

A wealthy businessman and State Department Special Representative, Curtis B. Munson, was tapped to consult with “Naval and Army intelligences and the F.B.I.” (Federal Bureau of Investigation) as to whether U.S. residents of Japanese descent—about 127,000 in the continental U.S. and Hawaii—posed a security risk. Munson spent a week in each of the 3 West Coast naval districts. He interviewed Japanese nationals, Japanese Americans, as well as those who knew them well. He researched Japanese American racial, cultural, associational, religious, and political factions and social divisions. The results filled several reports on what collectively was called the “Japanese Question on the West Coast,” which Munson sent to presidential envoy John Franklin Carter in October 1941 and which Roosevelt also read. Carter submitted Munson’s compilation of his West Coast notes to Roosevelt on this date, November 7, 1941. Copies were forwarded to U.S. Navy brass and Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson.

In examining national security risks on the U.S. West Coast, Munson divided residents of Japanese ancestry into 3 groups. There were the Issei (pronounced “ee-say”), immigrant first-generation Japanese who remained citizens of Japan; they comprised roughly 33 percent of the target community. Then there were the Nisei (pronounced “nee-say”) who were U.S.-born second-generation Japanese; they comprised close to 66 percent of the target community and were rapidly growing in numbers. Lastly there were the Kibei (pronounced “kee-bay”); they were also U.S.-born second-generation Japanese, but they spent all or part of their life in Japan. The Issei, age 55 to 65+, had weakened loyalty to the land of their birth by virtue of making their home in the U.S. and bearing children here. The Issei were strongly attached to the land as farmers, the sea as fishermen, and to their U.S. businesses and jobs, Munson wrote. The Nisei, age 1 to 30, “in spite of discrimination against them and a certain amount of insults accumulated through the years from irresponsible elements, showed a pathetic [!] eagerness to be Americans.” Munson considered the Kibei “the most dangerous” of the 3 groups, standing closer to the Issei than to the Nisei owing to their schooling in Japan. He partly walked back his warning about the Kibei, remarking “all a Nisei needs is a trip to Japan to make a loyal American out of him” because “[t]he American-educated Japanese is . . . treated as a foreigner and with a certain amount of contempt there.”

Recapping his findings, Munson ended his report by stating: “There is no Japanese ‘problem’ on the [U.S. West] Coast. There will be no armed uprising of Japanese . . . in case of a war between the United States and Japan. . . . There will be undoubtedly some sabotage financed by Japan and executed largely by imported agents. . . . For the most part the local Japanese are loyal to the United States or, at worst, hope that by remaining quiet they can avoid concentration camps or irresponsible mobs.”

Alas, in the wake of Japan’s December 7–8, 1941, air and naval strikes on U.S. military assets at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, the Philippines, and Wake Island, detention camps sprang up almost overnight to incarcerate all but a few Japanese nationals and Japanese Americans living in California, Oregon and Washington states, and a third of Arizona. Under Roosevelt’s February 19, 1942, Executive Order 9066, the U.S. committed the worst official civil rights violation in modern American history. (See photo essay below.)

Executive Order 9066 Cleared the Way for the Forced Exile and Relocation of West Coast Enemy Aliens and Japanese Americans to a New Existence in Detention Camps Far from Their Homes

|

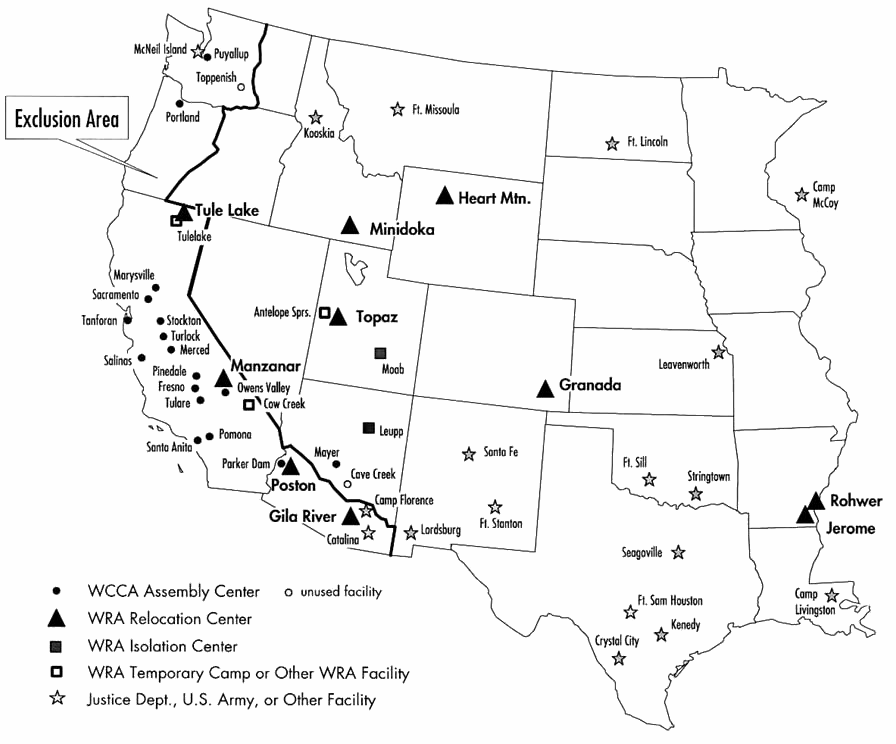

Above: Map showing (a) the massive World War II exclusion area (Military Areas 1 and 2) and (b) dozens of sites of confinement in the continental U.S. for over 126,000 Japanese nationals (“alien enemies”) and Japanese American citizens (labeled “non-alien enemies”) who primarily resided in 4 Western states as well as for over 31,000 suspected enemy nationals and their families interned under the Enemy Alien Control Program. Ten hastily built confinement sites, euphemistically called “relocation centers,” are identified by black triangles. The relocation centers were located in 7 states all west of the Mississippi River and cost the government $40 million annually to operate. All these centers were built in out-of-the-way places, many in desolate high deserts or swamp land. Identified by stars are facilities administered by the U.S. Department of Justice and the U.S. Army. It was to these often former Civilian Conservation Corps camps that Japanese arrested between December 8, 1941, and early 1942 were exiled indefinitely—that is, before Executive Order 9066 was in place. Indeed, the full extent of wartime incarceration includes thousands of German and Italian nationals living in the U.S. or deported from Central and South America, plus relocated Alaskan natives, Japanese Latin Americans, and some Japanese Hawaiians. These unfortunate people, along with Japanese nationals and Japanese Americans, were incarcerated in 75 U.S. government-run facilities. On December 17, 1944, the Roosevelt administration rescinded Executive Order 9066, ending mass forced relocation and allowing people who were incarcerated to return to the West Coast exclusion area. Except for Tule Lake Segregation Center in Northern California, the WRA camps would be emptied by the end of 1945. In the map legend WCCA = Wartime Civil Control Administration and WRA = War Relocation Authority, successor to WCCA.

|  |

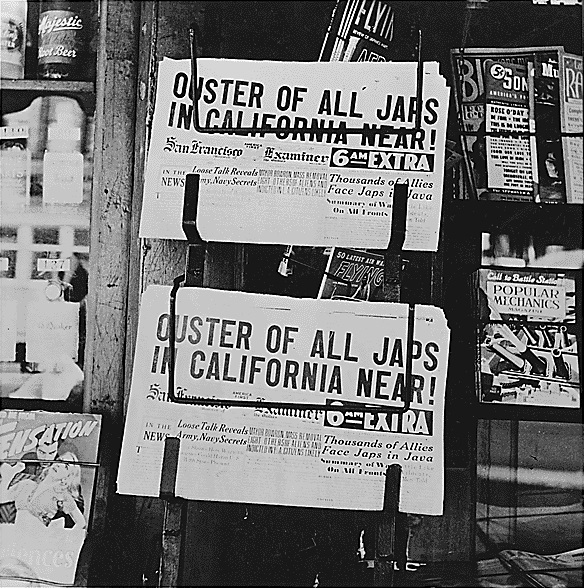

Left: “OUSTER OF ALL JAPS IN CALIFORNIA NEAR!” San Francisco Examiner headlines of Japanese relocation, February 27, 1942. Photo by Dorothea Lange. Lange was 1 of 3 photographers the WRA hired in 1942–1943 to take photos of the 10 WRA-run confinement camps. Two other photographers were Clem Albers and Francis Stewart.

![]()

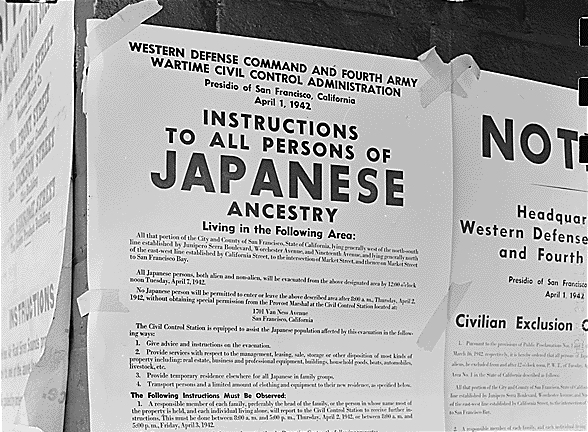

Right: Official notice of exclusion and removal, April 1, 1942. Photograph by Dorothea Lange. The posted exclusion order directed Japanese Americans living in the first San Francisco section to evacuate. Years before the December 7, 1941, Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, the U.S. government had drafted plans to round up and incarcerate some Japanese Americans and Japanese nationals and had already placed some West Coast communities under surveillance. This in spite of year’s worth of FBI and naval intelligence data that attested to residents of Japanese descent posing no national security threat.

|  |

Left: With luggage tags affixed to their clothing—an aid in keeping family units intact during all phases of their forced removal—members of the Moriji Mochida family await an evacuation bus in Hayward, Alameda County (San Francisco Bay area), California, May 8, 1942. On the luggage tags was written the family’s designated identification number. Mochida’s youngest child was 3. The Mochidas had operated a 2‑acre/0.8‑hectare nursery and 5 greenhouses in San Leandro, Alameda County, before their incarceration. Photograph by Dorothea Lange.

![]()

Right: The forced exodus of Japanese in Los Angeles started in late March and April 1942. Staring into uncertainty 2‑year-old Yuki Okinaga Hayakawa, clutching a tiny purse and an apple with a few bites gone, waits with the family’s allotment of baggage before leaving a chaotic scene at Los Angeles’s Union Station. The child and her single mother eventually arrived, like most Japanese Angelenos in March and April, at Manzanar War Relocation Center, more than 200 miles/322 kilometers north of LA in California’s Owens Valley, which would be their home for the next 3½ years. Each displaced family member was permitted to take bedding and linens (no mattresses), toilet articles, extra clothing, and “essential personal effects,” but nothing more; in other words, only what could be carried. Photograph by Clem Albers.

|  |

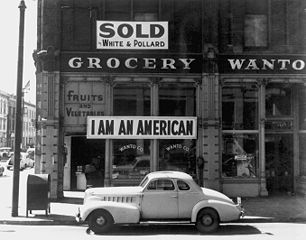

Left: The Matsuda family of Oakland, California, closed this grocery and Japanese goods store in March 1942 following orders to persons of Japanese descent to vacate certain West Coast areas (Military Area 1; see map above). Son Tatsuro, a University of California graduate, placed the “I AM AN AMERICAN” sign on the family’s store front soon after the events at Pearl Harbor. Declarations like this family’s were insufficient to overcome the suspicion and contempt directed at people who looked like the enemy and who, it was commonly assumed at the time, remained loyal to Japan and its emperor Hirohito (posthumously referred to as Emperor Shōwa). Photograph by Dorothea Lange.

![]()

Right: In 1944 the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the exclusion orders, described by many Americans as the worst official civil rights violation in modern U.S. history. After years of lawsuits and negotiations, on August 10, 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which formally acknowledged that the wartime exclusion, mass removal, and confinement of Japanese Americans had been unreasonable and unconstitutional. The act granted $20,000 in reparations to each surviving Japanese American (about 82,000 people), costing the U.S. Treasury $1.6 billion. It took a decade to locate all eligible U.S. recipients and deliver them their checks and formal apology. A late 20th-century study concluded that the internal government decisions that led to President Roosevelt issuing Executive Order 9066 were based on racial prejudice, wartime hysteria, and failed political leadership.

Injustice Camouflaged as Military Necessity: Japanese American Internment During World War II

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click