ROOSEVELT DECLARES LIMITED NATIONAL EMERGENCY

Washington, D.C. · September 8, 1939

On this date in 1939, eight days after Nazi Germany invaded neighboring Poland and triggered World War II in Europe, President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared a state of “limited national emergency.” The underfunded and undermanned U.S. military forces were strengthened, and the next year Congress provided major military budget increases, which led to the military services shaking themselves out of their peacetime stupor.

A year later, in September 1940 during the height of the German Blitz on London, the president signed the Selective Training and Service Act, the first peacetime conscription in U.S. history. All male citizens between the ages of 21 and 35 were required to register for the military draft, beginning on October 16. By that date more than 16 million men had complied when the first draft numbers were drawn. (By the end of 1942 the number of registrants had jumped to 42 million.) Service was for one year only. The Army’s Quartermaster Construction Division began building housing and recreation facilities for over 1.2 million men at 245 locations. Originally estimated at $516 million, the actual costs to build the camps ballooned to almost one billion dollars. The size of the U.S. Army grew from 267,767 men on June 30, 1940, to 1,460,998 by the middle of 1941, in part because the National Guard was assimilated into the regular army.

The Two-Ocean Navy Act became law on July 19, 1940. At $8.55 billion, it was largest naval procurement bill in U.S. history, increasing the size of the American combat fleet by 70 percent with the addition of 257 ships, among them 18 aircraft carriers, 7 battleships, 43 submarines, and 115 destroyers. The naval ships and striking power were designed to surpass “any combination of foes.” The Navy also requested 15,000 aircraft. The Navy Department’s Marine Corps expanded recruit training depots at Parris Island, South Carolina, and San Diego, California. From 19,432 officers and enlisted men in June 1939, the Corps expanded to a little over 66,000 at the end of November 1941—a week away from Pearl Harbor.

With war clouds on the Pacific horizon and tongues of flame everywhere in Europe and North Africa, it is noteworthy that one year after passage of the Selective Service Act a bitter political fight broke out when Congress proposed extending tours of duty by another year. The extension bill passed by a single vote.

![]()

1940 Selective Service Act and the Growth of the U.S. Marine Corps

|  |

Left: On September 16, 1940, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Selective Training and Service Act, the first peacetime draft in American history. Men between the ages of 21 and 35 were required to register at one of 6,500 local draft boards. Later the minimum age would be lowered to 18 and the upper age limit bumped to 64. Originally the act provided that not more than 900,000 draftees were to be in training at any one time, and they could only serve in the Western Hemisphere for one year. Draftees later would be required to serve anywhere they were sent for the duration of the war plus six months. Nearly 50 million men registered for the draft during World War II. Between 1940 and 1947—when the wartime selective service act expired after extensions by Congress—over 10 million men had been inducted into military service.

![]()

Right: Newly enlisted U.S. Marine Corps recruits wait at the Yemassee Train Station for transport to the Marine Corps Recruit Depot at Parris Island, South Carolina, 29 miles away, in November 1941. During the last month of peace, 1,978 men enlisted in the Corps. In December, following Pearl Harbor, enlistments jumped 500 percent, to 10,224. That number was smashed by a record of 22,686 enlistments in January 1942.

|  |

Left: Recruits at the Parris Island rifle range practice “snapping in.” This was a repetitive process of dry firing. It drilled into boots the correct system of weapons handling, sight alignment, and trigger manipulation.

![]()

Right: Recruits fire their service rifles at Camp Matthews rifle range in La Jolla, California, near the Marine Corps Recruit Depot San Diego. Rifle marksmanship was so important that recruits spent more time developing this skill in boot camp—two weeks—than any other single instructional subject. At the peak of the base’s activity in 1944, Camp Matthews put 9,000 recruits through marksmanship training every three weeks.

|  |

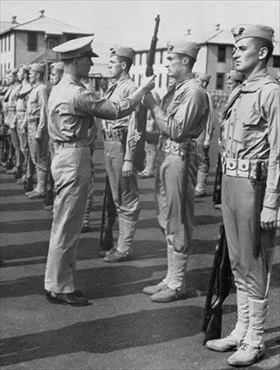

Left: Boots undergo a personnel inspection conducted by one of their company officers at Parris Island Recruit Training Depot. Immediately following the Japanese attacks of December 1941, the Marine Corps’ authorized strength increased from 75,000 to 104,000 Marines. These huge numbers put an immense strain on the recruit depots. Boot camp was cut from seven weeks in November 1941 to five weeks on January 1, 1942. A month and a half later the training schedule was increased to six weeks for newly forming platoons and in March 1942 training went back to the seven-week schedule.

![]()

Right: When President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8802 on June 25, 1941, to prohibit racial discrimination in the national defense industry, the Montford Point facility at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, became the site of recruit training for the first African Americans to serve in the Marine Corps.

Building Up the U.S. Armed Forces, 1940

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click