ROMMEL’S AFRIKA KORPS ORDERED TO LIBYA

Fuehrer HQ on the Obersalzberg, Germany • January 19, 1941

On this date in 1941 Adolf Hitler and Italian leader Benito Mussolini began 2 days of crisis talks at the Berghof, Hitler’s palatial Alpine residence whose enormous sliding window afforded magnificent views of nearby Berchtesgaden and, in the distance, Salzburg, Austria. High on the agenda was the failure of Mussolini’s army to liquidate Greece in 2 weeks, as the strongman had boasted to Hitler on October 18, 1940, the day the Italian invasion of Greece began.

In North Africa the Italian Tenth Army in Eastern Libya (Cyrenaica) ceased to exist after being mauled by Gen. Archibald Wavell’s British Eighth Army in Operation Compass (December 1940 to February 1941). Wavell’s army had killed 3,000 Italian soldiers, taken 115,000 prisoners, and destroyed 400 tanks, nearly 1,300 artillery pieces, and almost as many aircraft while suffering few losses of its own. Hitler was convinced that the Italian armed forces could neither be trusted nor even know how to use the weapons they possessed to reverse their sorry performance.

So it was that Hitler, overriding his own high command, authorized a “blocking force” of several German motorized and armored divisions to Italy’s Libyan colony, including the nucleus of the famous Deutsches Afrikakorps. Led by 49‑year-old Gen. Erwin Rommel, who had been the HQ commander in Poland and a brilliant tank commander in the Nazi invasion of France in 1940, the first of these units arrived between mid‑February and mid-March 1941. Additional units arrived in late April and into May.

Fate smiled on Rommel as the British drained men and equipment from Egypt to intervene in a losing campaign to save Greece from Mussolini’s and Hitler’s clutches. The imbalance of forces in North Africa soon had a disastrous outcome for British fortunes there, while it turned Rommel into the “Desert Fox,” securing him and the Afrika Korps a legendary place in military history.

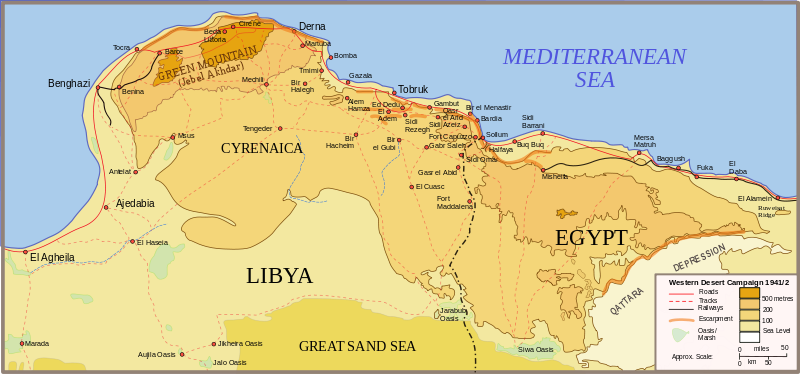

The Afrika Korps battled the British back and forth across the dry, hot sands of the Western Desert—at places like El Agheila, Gazala, Tobruk, and El Alamein—for much of the next 2 years. Neither the Germans nor the Italians would be finished off until mid‑May 1943, when bedraggled remnants of their armies in Tunisia surrendered to the Allies, whose presence had been strengthened by the Anglo-American Torch landings in Northwest Africa in November 1942. More than 250,000 German and Italian prisoners were taken, which ended the Axis presence in North Africa.

Cyrenaica, Eastern Libya, and Western Egypt, 1941–1942, Site of Seesaw Engagements Between Axis and Allied Armies

|

Above: Map of Cyrenaica, Eastern Libya, and Western Egypt, 1941–1942.

|  |

Left: Approximately 25,000 Italian defended the important harbor town of Tobruk in Cyrenaica. After a 12‑day period building up forces around Tobruk and softening up Italian defenses with heavy artillery bombardment, Australian, British, and Free French units took the town 1 day after launching an attack on January 21, 1941. The Tobruk prize yielded over 25,000 prisoners, 236 field and medium guns, 62 tankettes (small military tanks), 23 M11/39 medium tanks, and more than 200 other vehicles.

![]()

Right: British Vickers Mark VIB light tanks on desert patrol, August 2, 1940. First produced in 1936 for the dual roles of reconnaissance and colonial warfare, the lightly armored Mk VI possessed a crew of 3—commander/radio operator, gunner, and driver. Its main armament was a .50‑inch Vickers machine gun. In a December 12, 1940, attack, the low-clearance light tanks got bogged down in salt pans and were severely mauled by the Italians.

|  |

Left: Like the lightly armored Vickers Mark VI tank, Italy’s Fiat L3 tankettes were machine gun-armed. First built in 1933, L3s and their midget variants carried a 2‑man crew (driver and gunner) and were mainly used for light infantry support and reconnaissance. Relatively inexpensive to build, 300 Italian tankettes saw service against Haile Selassie’s mostly untrained and poorly equipped soldiers in Ethiopia (1935–1936), where they fared poorly, and in Spain, France, the Balkans, Libya, and Italian East Africa. In this photo a captured L3 cc on the left and an L3/35 on the right are shown here on the harbor road overlooking Bardia, Libya. At the start of World War II the majority of Italy’s armored vehicles was composed of tankettes, which Italian soldiers derisively called “sardine cans” and “vanity cases.” The British Army in North Africa roundly disabused Mussolini of his delusion that his tankette units represented a genuine force of armored might.

![]()

Right: Operation Compass was a complete success. Allied forces advanced 500 miles/805 km from inside Egypt to Central Libya, suffering just over 1,700 casualties and capturing 130,000 Italian prisoners, including 22 generals. In this photo from January 6, 1941, a column of Italian prisoners captured during the assault on Bardia, Libya, is marched to a British Army base for eventual transport to prison camps in England, North America, and elsewhere in the Commonwealth.

Axis and Allied Forces Battle for Control of North Africa, 1940–1943

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click