ROMMEL’S AFRIKA KORPS MAULED, SEEKS EGYPT EXIT

El Alamein, Egypt · November 2, 1942

On this date in 1942 in northern Egypt, Gen. Erwin Rommel (aka “Desert Fox”), brilliant commander of the German Afrika Korps, signaled to Adolf Hitler that he and his men would have to retreat after the British Eight Army, led by Lt. Gen. Bernard Montgomery, decisively bested them at the Second Battle of El Alamein (October 23 to November 11, 1942). El Alamein—66 miles west of the port city of Alexandria on the Egyptian Nile—was the turning point in the Allies’ back-and-forth slugfest in North Africa, and it ended Axis hopes of occupying Egypt, taking control of the Suez Canal, and gaining access to the Middle Eastern and Persian oil fields. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill famously said of the North African campaign, “Before Alamein we never had a victory. After Alamein we never had a defeat.” (It was Montgomery’s greatest triumph; he took the title “Viscount Montgomery of Alamein” when he was made a member of British nobility after the war.) Montgomery was blessed with numerical superiority in men and particularly equipment after the arrival of Spitfire airplanes, 6‑pounder antitank guns, and American-built M4 Sherman tanks with their turret-mounted 75mm high-velocity gun capable of penetrating the armor of any German tank. Rommel, pushed back into Italian-held Libya, made a stand at El Agheila (Al-‘Uqaylah) on the Gulf of Sidra in November and December 1942, but he was eventually outflanked. Since retreating from Egypt, Rommel’s Afrika Korps (or Panzerarmee Afrika, as it was now called) had lost roughly 75,000 men, 1,000 guns, and 500 tanks. His army was bested south of Tripoli (at El Buerat) at the end of December, but the Desert Fox succeeded in evacuating the remnants of his forces to Tunisia in January 1943. The Anglo-American Torch landings in neighboring Algeria and further east in Morocco the previous November dashed Rommel’s plans to go on the offensive and consolidate the German hold on Tunisia. By mid-1943, all remaining German and Italian forces in North Africa—some 250,000 strong minus the invalided Rommel—were swept up into Allied captivity. The Italian barn door as it were stood wide open, beckoning the Allies to begin their next operation, Operation Husky (July 10 to August 17, 1943), the invasion of Europe.

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”ASINList” width=”600″ height=”200″ title=”Recommended Reading” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”False” show_border=”False” asin=”0711028532,0142003948,1844156834,0764321404,081170419X,1841768677,0811705919,0811734137,1585677388,0521509718″ /]

Precursor to Victory at El Alamein: The Battle of Alam el Halfa

|

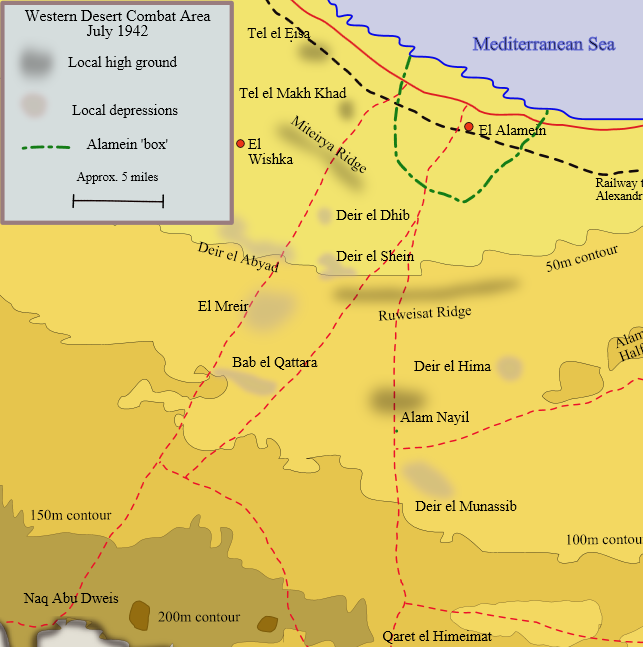

Above: The Battle of Alam el Halfa (August 30 to September 5, 1942) took place south of El Alamein. (Alam el Halfa appears as a ridge on the right edge of the map.) It was Montgomery’s first battle in North Africa, and his military doctrine was put to the test. Rommel’s objective was to defeat Montgomery’s British Eighth Army before Allied reinforcements made an Axis victory in Africa impossible. Thanks in part to Montgomery’s superior firepower and Allied mastery of the skies, the Battle of Alam el Halfa and the widely famous follow-on Second Battle of El Alamein (October 23 to November 11, 1942) were the last major Axis offensives in North Africa.

|  |

Left: PzKpfw IIIs (Panzerkampfwagen IIIs) of Rommel’s 21st Panzer Division advance with infantry support in Egypt in this photo from circa May 1942. On August 31, 1942, they led the assault to outflank British positions during the Battle of Alam el Halfa, but by then Montgomery’s Eighth Army was sufficiently equipped to repulse them, ending Rommel’s lightning advances in the western desert.

![]()

Right: Seven captured German special-purpose (Sd Kfz) 135/1 self-propelled 150mm howitzers from the 21st Panzer Division near El Alamein, October 1942. During the Second Battle of El Alamein, the 21st Panzer Division was reduced to four tanks and fought a rear-guard action all the way to Tunis. The remnants of the division surrendered to the Allies on May 13, 1943.

|  |

Left: A British-built, two-man-turret Mk3 Valentine tank in North Africa carries Scottish infantrymen. The Valentine tank was extensively used in the North African Campaign, but it shared the common weakness of British tanks of the period: its 2‑pounder gun lacked high-explosive (antipersonnel) capability, and it soon became outdated as an anti-tank weapon, too. By 1944 the Valentine had been almost completely replaced in European front-line units by the Churchill (Infantry Tank Mark IV) and the U.S.-made M4 Sherman tank.

![]()

Right: Maintenance work being carried out on a Hawker Hurricane during the British defense of Tobruk, Libya, 1941. The Hawker Hurricane was the Allies’ most useful aircraft in North Africa owing to its durability, an attribute very important in harsh desert conditions. The Hurricane played multiple roles in North Africa: photo-reconnaissance, patrolling, fighting, and bombing. The Hurricane developed into a lethal tank-buster that was first exploited to the max at Alam el Halfa, where Rommel’s retreating Afrika Korps was bombed day and night.

Battle of Alam el Halfa, August 30 to September 5, 1942, Sets the Stage for Rommel’s Defeat

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click