REINHARD HEYDRICH NEW CZECH MILITARY GOVERNOR

Prague, Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia • September 27, 1941

On this date in 1941 SS-Obergruppenfuehrer Reinhard Heydrich arrived in Prague to take up his post as Acting Reich Protector of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. Five days later the new military governor of Czech lands, which Germany had seized in March 1939, outlined his hardline agenda at Prague’s Černín Palace to a select gathering of Nazi officials. Heydrich was the perfect candidate for getting maximum results out of the hapless people in his new fiefdom. Infamous head of the sinister Reichssicherheitshauptamt (Reich Security Main Office, RSHA), whose departments included the Nazi Party’s intelligence agency (Sicherheitsdienst, SD), the Criminal Police (Kripo), and Gestapo (Geheime Staatspolizei, Secret State Police), the tall, Nordic-looking 37‑year-old SS general was tapped by Adolf Hitler to replace his “weak” civilian appointee, Baron Konstantin von Neurath, who went on indefinite sick leave.

Now that Hitler’s elite paramilitary Schutzstaffel (Protection Squad, SS) pulled the levers of power in the Czech capital, Heydrich double downed on the 7.5 million inhabitants of Czechia, the western half of former Czechoslovakia more widely known in English as the Czech Republic. The Protectorate supplied up to a third of Germany’s armaments; Heydrich demanded more for the German war effort. He introduced a binary campaign of bribery and terror. To foster higher productivity and quality, loyal armaments workers and their families received extra food rations and benefited from state-funded welfare programs. Other war-related industries and the agricultural sector shifted into high gear for the Reich. But the German despot also unleashed a cold-blooded program that filled Czech prisons and graveyards with thousands of civilians and nearly every member of the Czech underground Central Leadership of Home Resistance (ÚVOD). Anti-German sentiment and resistance in the form of strikes, work slowdowns, boycotts, and sabotage were brutally suppressed.

Heydrich’s “whip and sugar” policy (his term) impressed Hitler but worried both President Edvard Beneš, who headed the Czechoslovak government-in-exile in London, and Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who had charged Britain’s Special Operations Executive (SOE) to “set Europe ablaze.” The 2 leaders settled on a secret mission to reenergize the paralyzed ÚVOD in Prague by parachuting in a team of assassins who would target the “blond beast.” Heading up the onsite SOE-planned Operation Anthropoid were Jan Kubiš and Jozef Gabčík, both senior NCOs in Beneš’s Czech Brigade in Britain.

Between their air drop on the night of December 28, 1941, and their attack on Heydrich’s unescorted open-top Mercedes 5 months later, Kubiš and Gabčík built a detailed picture of Heydrich’s movements. The panicky local Czech resistance, having barely survived the last SS dragnet, begged the 2 agents and their London masters to abort the attempt on the high-profile German’s life, fearing correctly their nation would suffer reprisals by the pitiless SS. London would not budge. On May 27, 1942, in the Prague suburb of Liben, Kubiš and Gabčík ambushed Heydrich and his driver at a hairpin curve. A single grenade (fused bomb) fell short of the seated Heydrich but exploded near enough to the right rear wheel to send splinters of metal and glass and upholstery horsehair and leather into his body. Though Kubiš suffered shrapnel wounds to his face, Heydrich was mortally wounded. (The assassination attempt was dramatized in the 2016 British-French-Czech film, Anthropoid: Resistance Has a Code Name, by British film director Sean Ellis.) Despite surgery, morphine, and blood transfusions, Heydrich died in great pain from septicemia (blood poisoning) in a Prague hospital on June 4, 1942.

Operation Anthropoid: The Perilous Plot to Kill Reinhard Heydrich

|  |

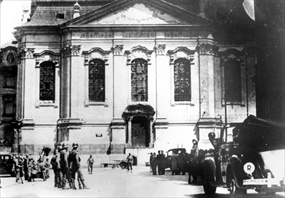

Left: Staff Sergeant Jan Kubiš (1913–1942), one of 9 Czechoslovak British-trained paratroopers dropped into Czechoslovakia as part of Operation Anthropoid, the daring and successful assassination of SS-Obergruppenfuehrer Reinhard Heydrich (1904–1942), Acting Reich Protector of Bohemia and Moravia for a brief 8 months. After Adolf Hitler and Reichsfuehrer-SS Heinrich Himmler, Heydrich was the third most powerful man in Nazidom. On June 18, 1942, 2 weeks after the tyrant’s death, Kubiš was wounded in a 6‑hour gun battle with German troops in his refuge, the crypt of the Church of Saints Cyril and Methodius in Prague. Kubiš died shortly after being taken to a hospital.

![]()

Right: Warrant Officer Jozef Gabčík (1912–1942) was a Slovak soldier in Czechoslovakia’s army-in-exile in England. Brandishing antitank grenades and a machine gun, Kubiš and Gabčík waylaid Heydrich, who was without a security escort, on May 27, 1942, as he commuted in his Mercedes-Benz convertible between his home and his office in Prague Castle. Gabčík, seriously wounded by a grenade in the same June 18 church firefight, committed suicide alongside other Czech and Slovak freedom fighters to avoid capture. On September 1, 1942, the spiritual leader of Prague’s Orthodox community and 3 priests who had sheltered Heydrich’s assassins were sentenced to death and martyred 3 days later. Over the next few weeks, 236 more individuals implicated in Operation Anthropoid were taken to Mauthausen concentration camp in Upper Austria and murdered in October 1942. The total number of dead Czechs was significantly less than the 10,000 hostages Hitler had initially ordered slaughtered in the wake of the attempt on Heydrich’s life, and way less than the 30,000 Himmler had wanted arrested and executed.

|  |

Left: The green Mercedes-Benz 320 Cabriolet B in which Reinhard Heydrich and his driver were riding on the morning of May 27, 1942; it lies abandoned at the sharp hairpin curve where the assassination attempt took place. The car sustained extensive damage when an antitank grenade thrown by Kubiš exploded near the right rear wheel, injuring Heydrich with fragments of glass, metal, horsehair, and other debris that later caused a fatal infection.

![]()

Right: In a May 11, 1942, radio message to Beneš’s government-in-exile in London, the clandestine ÚVOD pleaded that a less prominent German be considered for assassination, not the Acting Reich Protector. Following the violent attempt on Heydrich’s life, 12,000 German police, army, and Gestapo men raided 36,000 homes and apartments looking for clues and arrested 13,000 civilians in the largest police manhunt in Third Reich history. Eight Czech partisans were tracked to the small Orthodox Church of Saints Cyril and Methodius in Prague after they were betrayed by one of their Anthropoid team members. Surrounded by 800 SS men, the Czech patriots resisted but were eventually either killed (Kubiš died from gunshot wounds) or, like Gabčík, committed suicide rather than surrender to the enemy. The assailants’ heads, impaled on stakes, were put on display. Over the next weeks the bloodthirsty SS and Gestapo, following multiple leads, wiped out all anti-Nazi resistance in the Protectorate just as the ÚVOD had feared and warned London about. This frightful period (May 27 to July 3, 1942), in which over 5,000 death sentences were carried out on putative “anti-Nazi elements,” is remembered by Czechs as the Second Heydrichiáda (iáda = campaign of terror).

Biography of Reinhard Heydrich, “Hitler’s Hangman”

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click