REDS IMPOSE PEACE, U.S. CAPTURES ROCKET SCIENTISTS

SHAEF HQ, Versailles, France • May 2, 1945

On this date in 1945, a rain-sodden but peaceful day in Berlin, the battle for the war-ravaged Reich capital ended when General of the Artillery Helmuth Weidling surrendered his garrison to Soviet Lt. Gen. Vasily Chuikov, whose Eighth Guards Army was part of Marshal Georgy Zhukov’s First Belorussian Front. The Soviets claimed to have killed at least 100,000 enemy soldiers, taken 480,000 POWs, captured 1,500 enemy tanks and self-propelled guns, 4,500 aircraft, and 11,000 guns and mortars during the half-month offensive, the fourth largest of the war. An estimated 100,000 civilians perished in the Battle of Berlin; nearly 4,000 were registered suicides (April’s numbers), with countless more going unregistered.

Rape victims, the flipside of the Soviet orgy of murder, robbery, and looting, numbered between 95,000 and well past 130,000 and feature as one of the most horrific aspects of the Berlin battle. One Soviet war reporter recalled the Red Army as “an army of rapists,” whose motivation stemmed, in part, from hatred, revenge, a time to settle scores, and a penchant for plundering. Some of the worst rapists and looters were second-wave Soviet soldiers, often freshly released from German POW camps. Ten percent of those raped committed suicide. Young girls especially suffered atrocious injuries. (Victims were as young as 8‑year-olds but included pregnant women and women in their 60s.) Fathers killed their daughters and their wives rather than subject them to despoliation by Soviet soldiers. Some women in families suffered repeated rapes at Soviet hands. In the days when no antibiotics or contraceptives were available, cases of venereal disease and pregnancies spiked alarmingly. Abortions, normally illegal in Germany, were performed for months after the war, though their number is unknown. An estimated 5 percent of the children born in Berlin in 1946 were so-called Russenkinder.

Southwest of Berlin, in Southern Bavaria, while peddling his bicycle with a white handkerchief tied to his handlebars, Magnus von Braun, Wernher von Braun’s brother, encountered a shocked American private in the U.S. Seventh Army. Wernher von Braun and his team of V‑2 Peenemuende rocket engineers had just learned of Hitler’s death and sent the English-speaking younger von Braun to scout for someone to surrender to. Within days roughly 50 members of von Braun’s team were in U.S. custody.

Three weeks earlier American troops had overrun the underground V‑2 production facilities and the adjacent but nearly empty Mittelbau-Dora forced labor camp. Mittelwerk, as these production facilities were called, had been set up in Central (now Eastern) Germany for V‑2 production after the August 1943 bombing of the V‑2 Army Research Center at Peenemuende, near Stettin, on the German Baltic coast. At Mittelwerk thousands of prisoners were put to work building death-dealing V‑2 rockets under the direction of von Braun senior. GIs secured nearly 350 railway cars to cart away as many V‑2 rockets, parts, machine tools, and engineering drawings as possible before the area passed into Soviet hands under the agreement establishing Allied zones of occupation. Under tight security, the rockets—and von Braun and his rocketeers—eventually wound up, via Antwerp, Belgium, and New Orleans, at the White Sands Proving Ground in the New Mexico desert, the birthplace of U.S. rocket technology and space science.

Wernher von Braun, Mittelwerk V-2 Production Plant, and Slave Labor

|  |

Left: German rocketeers shortly after being taken prisoner by units of the 44th Infantry Division, U.S. Seventh Army, May 3, 1945, just over the Bavarian border in Reutte, Austria. Wernher von Braun, age 33, stands in the center of the photo, suffering from an arm broken in a car accident. His brother, Magnus von Braun, is seen at left edge of photo. Operation Paperclip, a decades-long covert project, brought many of von Braun’s team members (and their families) to the United States, where the scientists worked under contract with the U.S. Army Ordnance Corps.

![]()

Right: The Mittelwerk V-1 and V-2 factories occupied large tunnels underneath Kohnstein Mountain several miles/kilometers northwest of the town of Nordhausen in what is now Eastern Germany. The factories used slave labor from the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp, a subcamp of Buchenwald. About 60,000 prisoners from 21 nations passed through Mittelbau-Dora in an 18‑month period. An estimated 20,000 inmates died in the camp: 9,000 from exhaustion and collapse, 350 by hanging (200 for sabotage), while the remainder succumbed to disease and starvation. (It was largely due to the role of Albert Speer (pronounced “spare”) as Nazi Minister of Armaments and War Production in supplying slave labor to V‑1 and V‑2 production facilities that he received a 20‑year sentence at the postwar Nuremberg Trials.) Wernher von Braun visited the underground production facilities in the last months of 1943, when prisoners were engaged in building the tunnels, then twice between January and May 1944. “An extraordinarily depressing impression [swept over me],” von Braun told his German biographer in the late 1960s, “each time that I went into the underground plant and had to see the prisoners at work. It is repulsive to be suddenly surrounded by prisoners. The whole atmosphere was unbearable.” SS camp guards spared him an even more depressing sight seeing the above-ground Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp, where death stalked von Braun’s V‑weapon workers.

|  |

Left: A GI (right frame of photo) inspects a V-2 ballistic missile at the underground Mittelwerk facility. The 46‑ft/14‑meter tall V‑2 ballistic missile, which carried a one-ton warhead, was Nazi Germany’s secret weapon developed under the direction of Wernher von Braun by German scientists in an attempt to reverse the course of the war. About the time the Germans kicked off their V‑2 rain of terror weapons, they unleashed a propaganda leaflet campaign over England. “It’s time for the British people to listen to the words of reason of the Fuehrer,” the flyer read. “Give up this war. It is one you cannot hope to win.” British countermeasures consisted mainly of bombing V‑2 launching sites and supply depots. Roughly 250 V‑2s were found on the Mittelwerk assembly line in mid-1945 in various stages of completion when it was overrun.

![]()

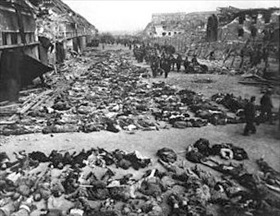

Right: Rows of dead inmates fill the yard of the Boelcke Barracks at Nordhausen Camp, April 12, 1945, one day after liberation. (Nordhausen and Dora were separate camps within the same 40‑plus Konzentrationslager Mittelbau complex.) Used as an overflow camp for sick and dying inmates from January 1945, Nordhausen saw its numbers rise from a few hundred to over 6,000, when up to 100 inmates died every day. Around 1,300 inmates died on the night of April 2, 1945, when British bombs destroyed substantial parts of the barracks during raids that destroyed three-quarters of the town of Nordhausen.

Mittelbau-Dora Concentration Camp and Underground Mittelwerk V-2 Production Plant. Skip first 45 seconds. (WARNING: Age-restricted video due to some disturbing scenes.)

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click