RED BALL EXPRESS TO CEASE CONVOY OPERATIONS

Utah Beach, Liberated France • November 13, 1944

On this date in 1944 Utah Beach ceased operations as an offloading site for men and supplies intended for Allied armies chasing eastward-fleeing Germans across France. Utah Beach was 1 of 5 Normandy invasion beaches where Allied men at arms and military equipment came ashore to liberate German-occupied France from Nazi and Vichy French tyranny. A week later, on November 19, 1944, Omaha Beach likewise ceased offloading operations. The main Allied supply bases in Western Europe now shifted to Antwerp (Europe’s largest port) and Ghent in Belgium and to Le Havre, Rouen, Cherbourg, and Marseille in France. Belgium’s Antwerp, 117 nautical miles/216 km from the port of Dover and 203 nautical miles/376 km from Southampton port in England, began unloading supplies for the Allied armies on November 26, 82 long days after its capture by British Field Marshall Bernard Law Montgomery’s 21st Army Group. Two days later Antwerp began functioning as the main supply base for Supreme Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Allied Expeditionary Force. These events, together with restoring the French rail system, brought closure to one of the most interesting truck convoy operations of World War II, the Red Ball Express.

The Red Ball Express truck convoy system began operating on August 25, 1944. “Red Ball,” a railroad term from the 1890s that referred to express shipping for priority freight, grew out of the recognition of the increasing supply difficulties the Allies had as their supply lines became more and more extended as they made their way to the German border. The French railway system had been bombed practically into ruination prior to D-Day and it would take weeks before enough French rail lines and stock were repaired and available, to say nothing about newly designed 6 in./15 cm portable gasoline pipelines being laid down. So for 83 days after the Allied breakout from Normandy in the first half of August, upwards of 25,000 men and 5,958 vehicles carried about 12,500 tons of supplies per day for the 28 hard-charging Allied divisions in France and Belgium that desperately needed constant resupply, especially of fuel and ordinance but occasionally replacement soldiers and Army nurses.

At the inauguration of the 24-hour truck convoy system, there were simply not enough large vehicles, trailers, or drivers to be had. So the Army raided units that had trucks and formed provisional truck units for the Red Ball Express. Soldiers whose duties were not critical to the war effort were asked—or tasked—to become drivers. The majority of the drivers and maintenance crew were African Americans. Each truck in the convoy was marked with a red disk at least 6 in./15 cm in diameter that represented a red ball, and each truck was identified with a number denoting its position in the convoy. A minimum of 5 trucks (2 drivers per truck) made up a convoy, escorted in front and back by jeeps, and trucks separated by 60 ft./18 m were to travel at an average speed of 40 mph/64 km/h. When convoys came to hamlets along the route, they had to slow to a crawl. Convoys were required to halt in place for 10 minutes every hour.

The Normandy breakout in August started a frenzied chase after the enemy that stretched Allied armored and infantry divisions supply lines to near collapse. Gen. Eisenhower recognized the Allied armies’ precarious situation when he wrote to the officers and men of the Red Ball Express and praised their performance: “The Red Ball Line is the lifeline between combat and supply. To it falls the tremendous task of getting vital supplies from ports and depots to the combat troops, when and where such supplies are needed, matériel without which the armies might fail. To you drivers and mechanics and your officers, who keep the Red Ball vehicles constantly moving, I wish to express my deep appreciation. You are doing an excellent job.”

Red Ball Express, the “Lifeline Between Combat and Supply”

|

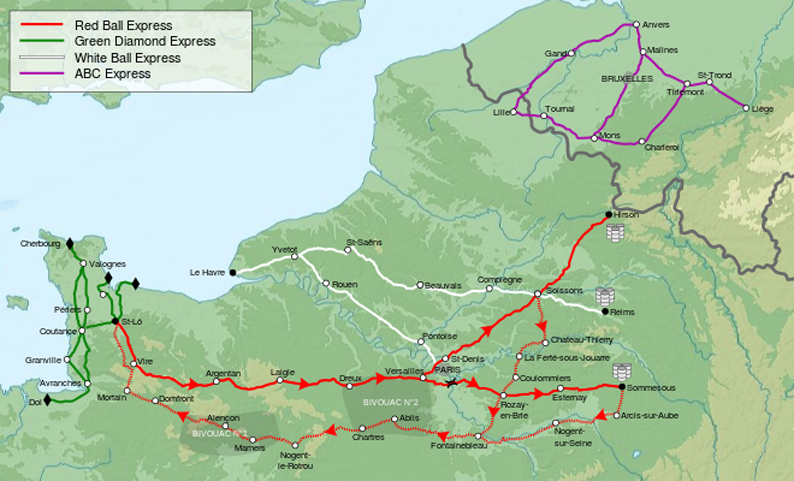

Above: Map of the Red Ball Express “loop-run” highway system (red lines and arrows), the famed truck convoy system that operated between August 25 and November 16, 1944, in France. To keep supplies flowing to the rapidly advancing Allied armies with minimal delay, 2 one‑way routes parallel to each other were opened from the strategic crossroads town of Saint‑Lô in Normandy (St-Lô, left side on map). The northern route was used for delivering supplies to intermediate and forward logistics depots ending at Sommesous in the east, including an extension northeast from Versailles to Hirson on the Franco-Belgian border. The southern route from Sommesous was used for returning empty vehicles and trailers to Saint‑Lô and beyond to the port of Cherbourg on the Cotentin Peninsula and the Mulberry artificial harbor at Arromanches (Gold Beach), nicknamed Port Winston after British prime minister Winston Churchill. Total length of the initial highway system, outbound and inbound, was roughly 300 miles/483 kilometers. Civilian and local military traffic was barred on the express routes. Other highway express routes in France around this time included the short-lived Green Diamond route connecting Cherbourg and the 5 Normandy invasion beaches with the Red Ball Express depot at Saint-Lô, the White Ball route connecting the port of Le Havre with Paris (southern branch) and Reims (northern branch), and the ABC (American-British-Canadian) Express Line established to fetch supplies from the Antwerp docks.

|  |

Left: Working hand in glove with the U.S. Army Quartermaster Corps and Transportation Corps, Red Ball Express drivers delivered 700,000 different items to the men and women in the European Theater of Operations (ETO). By the time the Red Ball Express shut down operations on November 16, 1944, truckers had delivered between 412,193 and over 500,000 tons of petroleum, oil, and lubricants (or POL), munitions, food, and other essentials to where it was most needed to keep the drive to the borders of Nazi Germany alive (sources differ on delivered tonnage). In this photo soldiers load trucks with rations bound for frontline troops. From left to right are Pvt. Harold Hendricks, Staff Sgt. Carl Haines, Sgt. Theodore Cutright, Pvt. Lawrence Buckhalter, Pfc. Horace Deahl, and Pvt. David N. Hatcher. The soldiers were assigned to the 4185th Quartermaster Service Company, Liege, Belgium, where a big supply depot was being established to support an Allied thrust into Western Germany.

![]()

Right: In the foreground is a trailer being loaded with hundreds of 5‑gallon/19‑liter jerry cans of gasoline. The Army maintained a reserve of 53,000,000 gallons of gasoline stored in jerry cans for Gen. Omar Bradley’s U.S. 12th Army Group alone. Apart from munitions, gasoline was the greatest need on the frontline and the highways thereto. Sometimes gasoline deliveries were made in the heat of battle. Said one soldier: “That takes guts. Our Negro outfits delivered gas under constant fire. Damned if I’d want their job.” A combat infantry division required 150 tons of gasoline a day, an armored division 350 tons per day. So gasoline fuel depots were set up along the Red Ball and other Express routes, sometimes partially manned by German POWs who filled vehicles’ gasoline tanks, checked tire pressures and oil levels, or cleaned windshields.

|  |

Left: A Red Ball truck convoy leaving a supply depot, probably Saint‑Lô owing to that community’s utter destruction from bombing and artillery. Truck tires took a real beating due to French roads being rough and littered with rubble, shell fragments, C‑ration cans, and bits of barbed wire. Many trucks were run on flat or low tires to the nearest Ordnance maintenance and repair shop, or they were patched on the spot by roving Ordnance units. Ten percent of the tires replaced (over 55,000 in September alone) were beyond recapping. Other maintenance issues along the route concerned underinflated tires, dry batteries, motors and differentials burned out for lack of grease and oil, nuts and bolts loosening and falling off the vehicle, and lubricating with too‑light oil.

![]()

Right: Military police were stationed at major checkpoints to direct bumper-to-bumper traffic, enforce traffic rules (e.g., no passing, blackout lights, so-called “cat’s eyes,” on front and rear of vehicles), and record pertinent data. On a typical day, 900 fully loaded vehicles, or 140 truck convoys, were on Red Ball highways round-the-clock moving sorely needed matériel to the forward areas. Depending on the recipient army (Courtney Hodge’s First Army or George S. Patton’s Third Army), a round trip on average took 54 hours. Speeding was a huge problem as drivers were pressed to speed deliveries to frontline troops. Red Ball drivers and mechanics removed the governors on the trucks’ carburetors that prevented drivers from exceeding 56 mph/90 km/h. Speeding, inexperienced or sleep-deprived drivers (some drivers drove 20 hours straight), overloaded trucks, shoddy maintenance, road fatigue, and the poor state of French roads caused numerous accidents, injuries, and deaths. The majority of vehicles repaired or brought in for repair (about 1,500 daily) were the result of wrecks, many of them single-vehicle accidents.

|  |

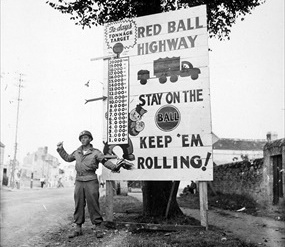

Left: Red Ball Express routes were marked with red balls. Corporal Charles H. Johnson of the 793rd Military Police Battalion waves on a Red Ball Express truck convoy near Alençon, France, a refueling and bivouac area on the Red Ball Highway, September 5, 1944. Behind Johnson is a large billboard that established the daily tonnage target for September 5 at 11,000 tons. (See right-facing arrow halfway up the column of numbers.)

![]()

Right: Nearly 75 percent of all Red Ball Express drivers were African Americans like the 3 soldiers shown in this photograph at an unknown location. That’s because well before and during the war U.S. commanders in general believed African Americans had little to no mettle or guts for combat. Consequently, the Army relegated blacks primarily to “safe” service and supply outfits like the Red Ball Express and the Graves Registration Service, while the Navy assigned them as mess stewards. All Marines are combat troops—the Corps refused to accept blacks into their ranks until 1942. Black Red Ball soldiers faced continual prejudice and hostility from white soldiers. Yet when the U.S. Army’s manpower pool ran low during the Battle of the Bulge (December 16 to January 25, 1945), many ex-Red Ball drivers joined the infantry, and by February 1945 a total of 4,500 blacks had signed on for combat duty.

U.S. War Department Presentation “Rolling to the Rhine” Recounts Red Ball Express Service History

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click