RECORD END-OF-YEAR DELIVERY OF B-29 HEAVY BOMBERS

Washington, D.C. • December 31, 1943

By this date in 1943 Boeing delivered its 92nd B‑29 Superfortress to the U.S. government after the giant bomber began rolling off the assembly line the previous September. Even before the country was at war and government funds had been allocated, Boeing had produced a prototype of the long-range heavy bomber and had submitted it to the U.S. Army for evaluation. The XB‑29 made its maiden flight on September 21, 1942. In all, Boeing built 2,766 B‑29s in Wichita, Kansas and Renton, Washington—the biggest and most technologically advanced plane any aircraft manufacturer ever built up to that time. Under contract from Boeing, the Glenn L. Martin Co. built 536 in Nebraska and the Bell Aircraft Co. built 668 in Georgia—2 planes a day in May 1945. As a weapons project, the B‑29 exceeded the nearly $2 billion cost of developing the atomic bomb (nearly $36 billion in 2025 dollars) by between 1 and 1.7 billion wartime dollars.

Early plans to use B-29s against Germany were scrapped when Boeing’s own B‑17 Flying Fortresses, introduced in 1938, and Consolidated Aircraft’s B‑24 Liberators, introduced in 1941, were found capable of operating from neighboring Britain and Italy. Hence, B‑29 Superfortresses were primarily used in the Pacific Theater. As many as 1,000 B‑29s at a time bombed Tokyo in 1945, destroying large parts of the Japanese capital. In March 1945 alone, more than 80,000 Japanese died in an incendiary raid on the city’s center—the highest loss of life of any aerial bombardment of the war. Finally, on August 6, 1945, a modified, or Silverplate, B‑29 named Enola Gay dropped America’s ultimate bomb, the world’s first atomic bomb, on Hiroshima. Three days later, on August 9, another Silverplate B‑29, Bockscar, immolated Nagasaki in a second effort to bring an end to the war.

On August 14, the last day of combat in World War War II, B‑29s laid waste to the Japanese naval arsenal at Hikari on the southern tip of Japan’s main island, Honshū. The next day, August 15, 1945, Emperor Hirohito (posthumously referred to as Emperor Shōwa) spoke to his nation by radio, acknowledging the B‑29’s pivotal role in the last half year when he said: “I have carefully assessed the situation of the world and conditions within Japan, and I think it is impossible to continue the war. . . If we continue the war, the whole country will be reduced to ashes, and I cannot endure the thought of letting my people suffer any longer. . . [Continuing the war] would lead to Japan’s annihilation” (rectified translation of imperial rescript by Noriko Kawamura). In lives alone the tally of Japanese dead or missing is estimated at 1,740,000, with 94,000 military wounded and 41,000 prisoners of war; 393,400 civilians were killed and 275,000 were wounded or went missing. By comparison 108,504 Americans who served in the Pacific Theater were killed, and 248,316 were wounded or listed as missing.

The B-29 Superfortress: Japanese Surrender Motivator

|  |

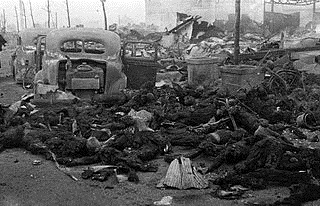

Left: The charred remains of Japanese civilians after the carnage and destruction wrought by Operation Meetinghouse, the March 9/10, 1945, nighttime firebombing of Tokyo. Toward the end of May, Tokyo was devastated 2 more times, leaving 3 million residents homeless.

![]()

Right: A virtually destroyed Tokyo residential section. Over 50 percent of Japan’s capital was reduced to ashes by the end of the war. After 1 bombing run, a B‑29 flier quipped: “Tokyo just isn’t what it used to be.”

|  |

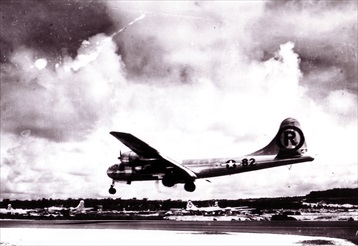

Left: Boeing, Bell Aircraft Co., and Glenn L. Martin Co. built 3,970 of these 4‑engine, propeller-driven B‑29 Superfortress heavy bombers between 1943 and 1946. With a wingspan of 142.25 ft./43.36 m and a length of 99 ft./30 m, the monster plane weighed in at 71,500 lb./32,432 kg empty to 140,000 lb./63,503 kg fully loaded. It had a range of 4,000 miles/6,437 km with 5,000 lb./2,268 kg bomb load. Normal bomb load ranged from 5,000 to 12,000 lb./2,268 to 5,443 kg, with a maximum of 20,000 lb./9,072 kg. Bombs had to be released alternately from the heavy bomber’s bomb bays to balance the aircraft during bombing runs. The B‑29 had a top speed of 399 mph/642 km/h at 30,000 ft./9,144 m. The aluminum-clad aircraft were left unpainted to save each plane several thousand pounds/over 900 kg of weight. “Silverplate” B‑29s—Superfortresses specially modified for atomic bombing missions—carried out the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9, 1945, respectively.

![]()

Right: Tokyo burns under a B-29 firebomb assault, May 26, 1945. B‑29 raids on Tokyo began on November 24, 1944, and lasted until August 15, 1945, the day Japan capitulated. Additional attacks on Tokyo were carried out by twin-engine bombers and fighter-bombers.

|  |

Left: Piloted by Lt. Col. Paul W. Tibbets, the Enola Gay, a Silverplate version of the Boeing B‑29 Superfortress, lands at Tinian’s North Field in the Mariana Islands at 2:58 p.m., August 6, 1945, after delivering “Little Boy” over Hiroshima, Japan.

![]()

Right: Hiroshima, Japan, after the atomic bombing of August 6, 1945. The area around ground zero in 1,000‑ft./305‑m circles shows barely any structures standing. The bomb detonated in the air and the blast was directed more downward than sideways. Some 70,000–80,000 people, or roughly 30 percent of the population of Hiroshima, were killed by the blast and resultant firestorm, and another 70,000 injured. It is estimated that 4.7 sq. miles/12 sq. km of the city were destroyed. In terms of buildings, 69 percent were destroyed and another 6–7 percent damaged.

Inside a Boeing B-29 Superfortress Aircraft Factory

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click